The Ancient Witch-Cult of The Basques

Not merely do the Basques have a unique place in the European history and culture, they are also unique within the evolution of European witchcraft, and when having finished this article, anyone interested in European witchcraft, occultism or pagan traditions will be surprised so little has been written about this topic!

‘Witches’ Sabbath’ (1797-98) Francisco Goya

The Basques (Euskaldunak) inhabit an area known as the Basque Country (Euskal Herria), a region, settled close to the westerly parts of the Pyrenees along the seashore of the Bay of Biscay and straddleling parts of N-central Spain and southwest France. The most accepted theory about the origins of the Basques labels them as one of the oldest inhabitants of Europe and the direct follow up of the Cro-Magnons in this region. Scientists conclude this because the Basque language has no relation to any Indo-European language whatsoever.

Let’s have a closer look at some intriguing facts about the ancient Basque religion, their spirit world, and other features in relation to traditional witch-lore classics, meaning: the Goddess & God, the causing of hail and thunder, a strange link to Lilith/Hekate, the Pan-like wild man of the woods (Pan, Leonard, the Horned One), nature spirits, the pointed hat, the Sabbath on Friday, the sexual element, the witch as a servant of the Goddess, and of course the big Black Billy-Goat of the Forrest.

Witches’ Sabbath or Akelarre or Aquelarra (1821–23) Francisco Goya

Goddess and God: Mari and Sugaar

Most of what is known about the elements of the original belief system of the Basques is based on the analysis of their legends, the study of place names and scant historical references to pagan rituals they practised. The Basques were a sincere pain in the ass of Christians who tried to convert them. Even in the 15th century, there were still Basques who stuck to the Old Religion and refused to be baptised. Christianity officially wiped out most of their religious traditions, but studying the English translation of Julio Caro Baroja’s Las brujas y su mundo (The World of Witches, 1964) there are substantial indications that some remains of the old magical traditions went underground and held out until the mid- twentieth century – locally, and in remote areas. Unfortunately the Christian missionaries had a certain advantage, as the transition of the name Mari, the Goddess of the Basques, into Maria or Mary, was of course piece of cake.

Legends connect Mari to the weather: when she and Maju travelled together hail would fall.

Mari, also called Mari Urraca, Anbotoko Mari (The lady of Anboto), and Murumendiko Dama (Lady of Murumendi), was a typical old chthonic (earth) goddess. She was married to the god Sugaar (also known as Sugoi or Maju) and resided in a grotto at the foot of a high mount – just like Hekate – and once the majority of ancient European and Middle Eastern goddesses. (See the very complete information on the chthonic goddesses in Will-Erich Peuckert’s masterpiece Geheim-Kulte, Heidelberg 1951.) Legends connect Mari to the weather: when she and Maju travelled together hail would fall. Her departures from her cave would be accompanied by storms or droughts, and which cave she lived in, at different times, would determine dry or wet weather; wet when she was in Anboto; dry when she was elsewhere. Other places where she was said to dwell include the chasm of Murumendi, the cave of Gurutzegorri (Ataun), Aizkorri and Aralar.

Lamiak, Giants and Wild Men of the Forrest

Mari was also the Queen of a class of genii called the Lamiak. The Lamia (plural: Lamiak, and not to be confused with the Greek Lamia) is a siren- or Nereid-like creature in Basque mythology. Lamiak, Laminak or Amilamiak lived in the river. They were really beautiful, and often stayed at the shore combing their long hair with a golden comb; they easily charmed men. They had duck or goose feet. In coastal areas, some believed in a variety, the Itsaslamiak, who lived in the sea, and had fish tails, like a mermaid. The duck, or goose feet are a quite remarkable feature, as some among you will have noticed. In the ancient literature, Lilith, a Semitic variety on Hekate, aka the Queen of Sheba, as she appeared before King Solomon, had duck or goose feet. Both Mari and Lilith were depicted as beautiful women with magical powers and the feet of a water bird; very suggestive of some ancient common root, though on the surface not culturally connected. Lilith dwelt in the wilderness amongst the satyrs.

The most famous wild man of the Basques is Basajaun. The Basajaunak were believed to have built the megaliths, spread all over Basque country.

A major class of genii in the Basque religion are the Mairuak, also called Maideak, Mairiak, Saindi Maidi (in Lower Navarre) or Intxisu in the Bidasoa valley. They were giants, wild men, or “wild man of the woods”, archaically the woodwose or wodewose, the mythical figure that appears in the artwork and literature of medieval Europe, comparable to the satyr or faun and to Silvanus, the Roman god of the woodlands. The most famous wild man of the Basques is Basajaun (plural: Basajaunak). The Basajaunak were believed to have built the megaliths, spread all over Basque country.

The Lady in Red

There are no recordings of any sacrifices made to Mari. Food was offered to lesser spirits (Lamiak, Jentilak, etc.), as recompense for their work in the fields. Apart from causing storms who would bring fertility to the land, one other function of Mari was helping travellers who were lost in the wilderness. One only had to cry Mari’s name aloud three times to have her appear over one’s head and the goddess would appear to help the person find his or her way back.

Mari is the main character of Basque mythology, having, unlike other creatures that share the same spiritual environment, a godlike nature. She was often described as a woman dressed in red. She is also portrayed as a woman of fire, woman-tree and thunderbolt. Additionally, she manifested herself in red animals (cow, ram, horse), and a black he-goat. There is also a link with Diana/Artemis as her idols usually feature a full moon behind her head.

Witches’ Flight (1797-98) Francisco Goya

Sugaar comes with storms and thunder

Sugaar (also Sugar, Sugoi, Suarra, Maju) is the male consort of Mari, associated with storms and thunder. He is normally imagined as a dragon or serpent. Unlike his female companion, Mari, there are very few remaining legends about Sugaar. The basic purpose of his existence is to periodically join with Mari in the mountains to generate the storms. The name Suga(a)r is derived from suge (serpent) and -ar (male), thus “male serpent”. Another theory derives the name from su (fire) and gar (flame), thus yielding “flame of fire”.

INTRODUCING AN ASTROLOGICAL REVOLUTION: Chiron and 84 other astrological meanings of asteroids belonging to the important Centaur-class are described in this revolutionary work. Centaurs are especially prominent in the horoscopes of original, weird, creative, magical and out of the box acting people. Among the described Centaur or Centaur-like asteroids are Aphidas, Hylonome, Bienor, Crantor, Eris, Gonggong, Dziewanna, Amycus, Okyrhoe, Echeclus, Orius, money-Centaur1998 BU48, Nessus, Pylenor, Pelion, ISON, Pholus, Narcissus, Asbolus, Zhulong, Kondojiro, Damocles, Hidalgo, Thereus and much more... For ordering this new astrology-bestseller click here.

Sugoi, another name of the same deity, has two possible interpretations, either a suge + o[h]i (former, “old serpent”) or su + goi (“high fire”). There is no likely etymology for the third name of this god, Maju. In Ataun, Sugaar is said to have two homes: the caves of Amunda and Atarreta. He was supposed to cross the sky in the shape of a fire-sickle, which was considered a forebode of storms.

In this region the locals also believed that Sugaar punished children that disobey their parents. In Azkoitia Sugaar is identified with Maju. He meets Mari on Fridays (the day of the Akelarre or Sabbat) conceiving then the storms. In Betelu Sugaar is known as Suarra and considered a demon. They say he travels through the sky in the shape of a fireball, between the mountains Balerdi and Elortalde.

In Ataun, Sugaar is said to have two homes: the caves of Amunda and Atarreta.

The division of a Goddess-God pair in representatives of the Watery/Earthy and Firery/Airy Elements is of course very archaic and classic. Both gods remain in the chthonic atmosphere. Therefore, they easily interchange their rank of a god with that of a demon or a daemon. Mari shares with Sugaar the association with various forces of nature, like thunder and wind. As the personification of the Earth, she may have been worshipped in association with the Earth goddess Lurbira.

To complete Mari’s portrait as a multitasking goddess, she was also regarded as the protectoress of senators and the executive branch. Important in the Basque religion is the central role of the Earth/Lurbira/Mari as a base or womb and a shelter from which all nature and life forces originate, return and are recharged.

Trials, Francisco Goya

The Sorginak or Witches

A similar interchangeability – in this case the one between human and deamon – is noticed about the Basque witches or Sorginak. On the one hand, they are the assistants of the goddess Mari in the shape of mythical creatures; on the other hand sorginak is also the Basque name for witches (brujas in Spanish) or pagan priestesses (though they could also be male) in human form. To make it even more confusing, sometimes sorginak are confused with the nymph-like Lamiak or even the Jentilak, who according to tradition built the local megaliths.

In time the usage of the term sorginak for a human witch prevailed. Sorginak, like other European witches, used to participate in the Sabbat, called Akelarreak locally. These mysteries happened on Friday nights, when Mari and Sugar were said to meet in the local sacred cave to engender storms. Sorginak, from the root sorgin, derived most likely from the combining of sor(tu) create and the suffix (e)gin to do, thus translating sorginak as Creators, or Those who create.

Folklore tells of sorginak transforming themselves into animals, most commonly cats. These cats are sometimes said to bother pious women that do not wish to go to the Akelarre (Sabbath). They were also accused of collecting monetary fines from the people who refused to go to their ecstatic gatherings, or from those witches that absented themselves from them. As always, there is confusion whether the Akelarre-gatherings were real or astral travels induced by psychotropic plants, or fungi, like ergot.

In case of the Basque witches there is strong evidence part of the gatherings were real. Even Julio Caro Baroja mentioned an eyewitness account of a nocturnal gathering in the fields in the 20th century. Yet the astral version must have been popular too, as it has its own stimulation spell for travelling to and back the Akelarre: Under the clouds and over the brambles! In many legends a failed witch (normally a man) says the spell inverted (Under the brambles and over the clouds) and arrives to the Akelarre quite bruised.

The sorginak travelled astrally; so they rubbed their bodies with unguents and drank potions made of psychotropic plants.

Akerbeltz

As expected the inquisitorial documents describe horrific practices of witches, like eating children or poisonings. In contrast however, popular legends do not mention these practices. The Sorgin is also a witch-spirit that turns people, mostly women, into witches of flesh and blood. These possessed witches then become a sort of Basque version of the North Italian Maledante: nasty and evil, aimed at spoiling food supplies and crops. Sorgin is a wicked spirit who is under Etsai’s (an angry red bull spirit, also known as Zezengori) and Akerbeltz’s orders.

Those who are bewitched, most of them women, due to the influence of this spirit, have special gifts and are evil. Sorgin is blamed for typical witch-clichés like the unexpected bad harvest, for the breakdowns at the mills, for he mysterious illnesses and deaths, for the wreck of ships, for hunters not catching anything, for the evil eye, etc. The sorginak acted together and on sacred days, at night they met as a coven.

They travelled astrally; so they rubbed their bodies with unguents and drank potions made of psychotropic plants. They knew the factures of the plants very well: poisonous, medicinal, hallucinogen, etc. They danced to the sound of the music and partook in sexual orgies. They despised Jesus Christ, worshipped Akerbeltz, and they gave their opponents the evil eye or cursed them by other means. These covens were called Akelarreak in Basque and the origin of that word lies in Zugarramurdi (Navarre), where the witches met in a field they called Akerraren Larrea (the meadow of the billy goat).

Pretty teacher, Francisco Goya

The Akelarre or Sabbath Field and the He-Goat Worship

The gathering place for the witches Sabbath is called the Akelarre (Aquelarre in Spanish). The most common etymology is that meaning meadow (larre) of the male goat (aker “buck, billy goat”). The Spanish Inquisition accused people of worshipping a black goat, related (in the Christian-Judean tradition) to the worship of Satan. In reality the Black He-Goat was either the god Akerbelz, or an animal form in which the Goddess Mari temporally incarnated. Red animals were other forms in which she manifested herself. Her son Mikelatz was also said to appear as a young red bull, when not assimilated with the storm god Hodei.

An alternative explanation of the word Akelarre could be that it originally was alkelarre, alka being a local name for the Dactylis hispanica, a species of grass, very common in Europe and Asia. It has been suggested the first etymology could have been a manipulation of the Inquisition, the fact being that the Basques did not know, during the 1609-1612 persecution period, or later, what the “akelarre” referred to by the inquisitors meant.

The word aquelarre is first attested in 1609 in a Spanish language inquisitorial briefing, as synonym to junta diábolica, meaning ‘diabolic assembly’. Basque terms transcribed into Spanish texts often by monolingual Spanish language copyists, were fraught with mistakes. Nevertheless, and as said before, the Black He-Goat or Akerbeltz is known in Basque mythology to be an attribute of goddess Mari and is found as far back in Antiquity as a votive dedication: Aherbelts Deo (“to the god Aherbelts”). In ancient times the Basques were known to the Greeks, who called them Ouaskonous (The people of The He-Goat), due to their habit of sacrificing goats to their gods. There is little information about Janicot, a fusion between Akerbetz and Basajaun, compiling a Pan-like figure, so often depicted in Medieval engravings as the central figure of the Sabbath. Both Doreen Vailante and Gerald Gardner considered Janicot the true and primordial Witch-God.

Akerbeltz was a protector and guide of witches and wizards, cared for domestic animals left under his protection, and cured diseases.

Akerbeltz or simply Aker, as he is sometimes called, had a double nature. He was a protector and guide of witches and wizards. Sometimes he showed his positive features and sometimes his dark side. When he was good tempered, his gifts were similar to Mari’s. In addition Akerbeltz cared for domestic animals, left under his protection and cured diseases. That’s why, in certain county houses, a black billy goat, was traditionally raised to protect the rest of the domestic animals.

There is evidence this spirit was worshipped in the Basque Country long before the arrival of Christianity. In the 3rd century A.D., the name Aherbelste appears in certain Roman inscriptions can be linked to Akerbeltz, at that time still having the status of a god, whose main task was also protecting domestic cattle. The Akelarreak (witches’ covens) were named after the places where they were held (always pasture lands for the goats). In those meetings, the sorginak worshipped Aker every Monday, Wednesday and Friday and put themselves under his command.

According to legend, Akerbeltz had an attitude against Christianity and he expressed his point of view to his followers. While Christianity was expanding, those who wanted to keep the old nature-believes took part in the covens, and in the 16th and 17th century, they formed a movement against the new social organization and Christian religion. In these days, according to legend, Akerbeltz was worshipped while the covens parodied the Christian mass. His followers offered him bread, eggs and money. After Akerbeltz had been drinking and the eating, legend tells, the spirit would dance with the witches to the sound of the Basque flute. And, indeed after much drinking, the Akelarreak would end with all participants having sexual intercourse.

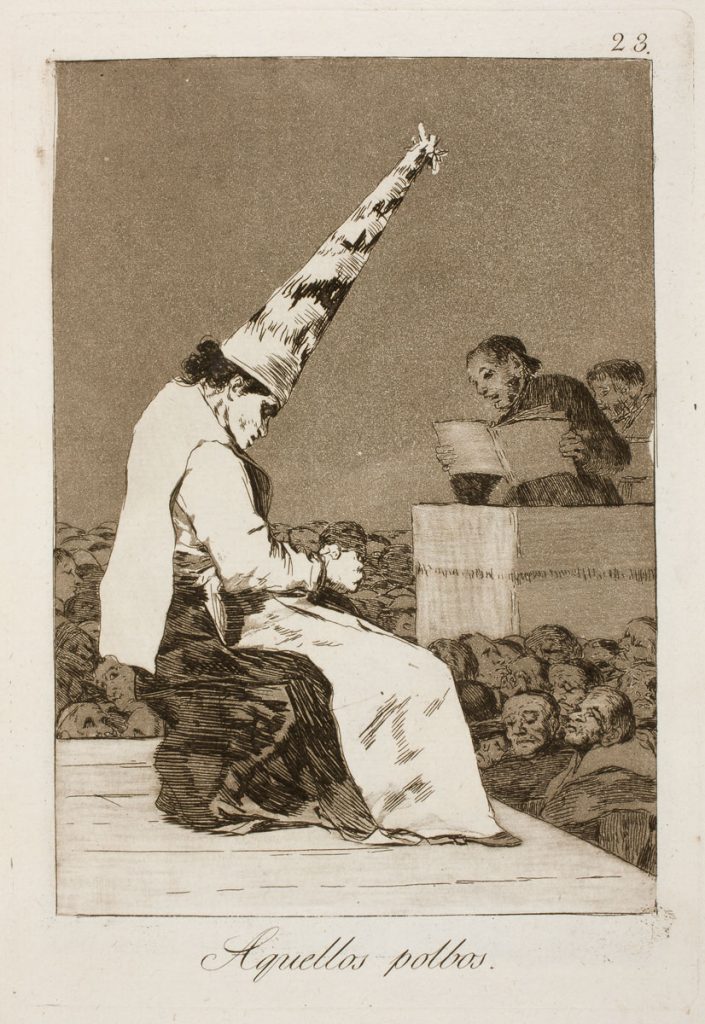

Those specks of dust, Francisco Goya

The persecutions and Witch-trials

The Basque witch-trials of the 17th century represent the most ambitious attempt at rooting out witchcraft ever undertaken by the Spanish Inquisition. The trial of the Basque witches in Logroño, near Navarre in northern Spain, which began in January 1609 against the background of similar persecutions conducted in Labourd by Pierre de Lancre, was almost certainly the biggest single event of its kind in history. By the end some 7,000 cases had been examined by the Inquisition. It caused a major trauma among the Basque population.

Pierre de Lancre considered Basques to be ignorant, superstitious, proud and irreligious.

De Lancres’ grandfather, Bernard de Rostegui (cf. Basque surname Aroztegi, ‘home of the smith’) a native of Lower Navarre, had changed his Basque surname for the French one of de Lancre upon migrating to Bordeaux. This familial denial seems to have influenced him into a deep hate against everything Basque. He considered Basques to be ignorant, superstitious, proud and irreligious. Basque women were in his eyes libertines and Basque priests were just womanizers with no religious zeal. He believed that the root of Basque natural tendency towards evil, was love of dance. All these biases are reflected in his work Tableau de l’Inconstance des Mauvais Anges et Demons, published in 1612. In this work, de Lancre sums up his rationale as follows:

“To dance indecently; eat excessively; make love diabolically; commit atrocious acts of sodomy; blaspheme scandalously; avenge themselves insidiously; run after all horrible, dirty, and crudely unnatural desires; keep toads, vipers, lizards, and all sorts of poison as precious things; love passionately a stinking goat; caress him lovingly; associate with and mate with him in a disgusting and scabrous fashion—are these not the uncontrolled characteristics of an unparalleled lightness of being and of an execrable inconstancy that can be expiated only through the divine fire that justice placed in Hell?”

De Lancre accused 30.000 Basques, including priests, of being infected with witchcraft. Once 5,000 fishermen, returning home from New Foundland, discovered that their loved ones had been burned, and started a riot. People accused of “witchcraft” often had to wear a long pointed hat, and here lies the origin of the depiction of witches in childrens books with pointed hats.

Today, the village of Zugarramurdi holds the Witchcraft Museum highlighting the appalling events of the early 17th century, where the memory of the victim villagers is dignified. Akelarre was a 1984 Spanish film by Pedro Olea, about these trials. Zugarramurdi now celebrates the witches with a feast by the cave on Midsummer’s eve, June 23, the folk date for the summer solstice. A satire movie located in Zurragamurdi and in a most original way displaying features of the witchcraft of the Basques (+ a lot of special effects) is Las Brujas de Zugarramurdi or Witching and Bitching. ♦

© 2017 Benjamin Adamah

VAMzzz Publishing book:

In her both pioneering and controversial work The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921), Margaret A. Murray posits the theory of an ongoing witch-cult in Western Europe, rooted in a once widespread religion, dating back to pre-historic times. In our revised publication of Lelands “Aradia” we included a list of historical data, running from about 600 BC up till the 19th century AD. The list is consisting solely of historical facts, taken from historical quotes, which prove indeed a continuous worship of Diana, Goddess of the wilderness, forests, refugees and… witches. Thus settling the controversy in favour of doctor Murray, yet we have been mining our data, primarily, in the North Italian tradition of the stregheria. The stregheria (from the Latin Strix = witch) has strong roots in Etruscan religion and magic. But an even more ancient culture than the Etruscan civilization is the culture of the Basques.

Aradia,

Gospel of the Witches

by Charles Godfrey Leland

English

ISBN 9789492355010

Paperback, book size 148 x 210 mm

174 pages

You may also like to read:

Spirit Beings in European Folklore

Water Spirits of Eastern Europe

Witches ointment

Why did Witches Want to Ride their Broomsticks?

Historical werewolf cases in Europe

The incubus or succubus – nightmare or astral sex date?

Hecate – The Calling of the Crossroad Goddess

Walpurgis Night

Stefan Eggeler: Walpurgis Night witches, Kokain (Cocaine) and other illustrations

Witchcraft paintings – Dutch 17th century

Rosaleen Norton, Daughter of Pan

Mysteries of the Ancient Oaks

Black Cat Superstitions

The Mystical Mandrake

Little Secrets of the Poppy

Datura stramonium or jimson weed or zombi-cucumber

Mountain spirits

Wild Man or Woodwose

Sprite

Claude Gillot’s witches’ sabbat drawings