Witches ointment

Witches ointment is an ointment or paste with which people (mostly women known as witches) are said to have rubbed themselves in order to fly to the witches sabbath in the late Middle Ages and at the time of the early modern witch persecutions.

A follower of David Teniers depicting a witch on a broomstick at her departure for the sabbat. Witches sometimes used broomsticks, but the flight-experience was in reality the psychotropic effect of the witches or flying ointment.

The ointment is known by a wide variety of names, including witches’ flying ointment, green ointment, magic salve, or lycanthropic ointment. In German it was Hexensalbe (witch salve) or Flugsalbe (flying salve). In Holland, vliegzalf (flying salve) or heksenzalf (witches’ ointment). Latin names included unguentum sabbati (sabbath unguent), unguentum pharelis, unguentum populi (poplar unguent) or unguenta somnifera (sleeping unguent).

Young Basque witch rubbing flying ointment

Witch ointments are ointment preparations made from psychoactive substances (especially from nightshade plants), the use of which can cause hallucinations or delusional dreams. To stigmatize “witches” as evil and demonic the “fat of children” is regularly mentioned by those who led the burning times to its horror climax.

The misogyne psychopath Heinrich Kramer (Institoris) describes in 1486 in the second part of his infamous Malleus Maleficarum (Hexenhammer, Hammer of the Witches) that witches could rise in the air because of an ointment made from children’s extremities. Even Francis Bacon listed as the ingredients of the witches ointment “the fat of children digged out of their graves, juices of smallage, wolfe-bane, and cinque foil, mingled with the meal of fine wheat.”

Highly toxic ingredients

Typical poisonous ingredients included belladonna or nightshade, henbane bell, jimson weed (Datura stramonium), black henbane, mandrake, hemlock, and/or wolfsbane, most of which contain atropine, hyoscyamine, and/or scopolamine. Scopolamine can cause psychotropic effects when absorbed through the skin.

Apart from these herbs mushrooms like the Amanita muscaria, commonly known as the fly agaric or fly amanita and ergot or the poison of toads (bufotenin) were used to trigger psychotropic effects, like out of body experiences, seeing Elemental and nature spirits, flying through the air or intense orgasms. Pigs fat was used instead of childrens’ fat.

In the ages these ointments were used frequently they made many casualties because of their toxicity and the problem that it is very difficult to estimate how much of the active psychotropic substance a herb contains. This differs due to ground quality, time of the year, weather, condition of the plant, moment of picking etc.. Even in modern times experimenting with these ointments can be fatal. The German historian, occultist and theosophist Carl Kiesewetter for exemple, author of Geschichte des Neueren Occultismus 1892 and Die Geheimwissenschaften, eine Kulturgeschichte der Esoterik 1895 died while testing an witches ointment recipe on himself.

To make a long story short: experimenting with witch ointment herbs is NOT advisable!

Poppy is suggested as antidote or “balancer” for belladonna.

One possible key to how individuals dealt with the toxicity of the nightshades usually said to be part of flying ointments is through the supposed antidotal reaction some of the solanaceous alkaloids have with the alkaloids of Papaver somniferum (opium poppy). This is discussed by Alexander Kuklin in his brief book, How Do Witches Fly? (DNA Press, 1999).

This antagonism was claimed to exist by the movement of Eclectic medicine. For instance, King’s American Dispensatory states in the entry on belladonna: “Belladonna and opium appear to exert antagonistic influences, especially as regards their action on the brain, the spinal cord, and heart; they have consequently been recommended and employed as antidotes to each other in cases of poisoning” going on to make the extravagant claim that “this matter is now positively and satisfactorily settled; hence in all cases of poisoning by belladonna the great remedy is morphine, and its use may be guided by the degree of pupillary contraction it occasions.”

The synergy between belladonna and poppy alkaloids was made use of in the so-called “twilight sleep” that was provided for women during childbirth beginning in the Edwardian era. Twilight sleep was a mixture of scopolamine, a belladonna alkaloid, and morphine, a Papaver alkaloid, that was injected and which furnished a combination of painkilling and amnesia for a woman in labor. A version is still manufactured for use as the injectable compound Omnopon. There is however no definite indication of the proportions of solanaceous herbs vs. poppy used in flying ointments, and most historical recipes for flying ointment do not include poppy.

Witches ointments in antiquity

Lucius spots the witch Pamphile using a trransformation ointment

There are no such ointment recipes from antiquity, but in the poetry there are two mentions of a substance which apparently gave flightability and which could be understood as a precursor of the late medieval witch ointments.

The poet Homer mentions in the Iliad (Chapter II, XIV) that the goddess Hera anointed herself with ragweed in order to reach Zeus on the Idaberg. Homer writes that she “[…] came to Zeus via the highest peaks and never touching the earth […]”, and that Zeus was very surprised at how quickly she had overcome the distance.

A second mention of a substance that bestowed similar abilities can be found in the novel Metamorphoses by the Roman writer Apuleius: The Hero of the Novel – Lucius – tells of the magical abilities of the witches from Thessaly, who would have possessed the ability not only to animate mandrakes to cause them harm, but also to transform and “fly out” their own form. The text says that the witch Pamphile undressed herself naked, took a tin with ointment and rubbed herself with it from head to toe. “Then she shakes all her limbs. These are hardly in a rolling motion when soft fluff is already coming out of them. In a moment strong feathers have also grown, the nose is horny and crooked; the feet are pulled together in claws. Pamphile stands there as an eagle owl!”

– Apuleius: Metamorphoses III, 21

Ovid and Seneca also report of such strigae (witches), which can turn into a night bird by means of ointment or ride on animals and objects through the air.

Middle Ages

Regino of Prüm writes in his De synodalibus causis et disciplinis ecclesiasticis libri duo (circa 906 C.E.) about women who ‘seduced…by demons…insist that they ride at night on certain beasts together with Diana, goddess of the pagans, and a great multitude of women; that they cover great distances in the silence of the deepest night...’.

Aconitum napellus, one of the poisenous plants used in some of the witches ointment recipes.

Abraham of Worms, a Jewish Kabbalist, reported at the end of the 14th century in his Buch Des Juden Abraham von Worms – Buch der wahren Praktik in der göttlichen Magie (Book The Jew Abraham of Worms – Book of True Practice in Divine Magic), of an ointment which he had both tried out himself and observed soberly in a young woman and which had the effect that “I flew to the place I had wished in my heart without telling her anything about it“. Although the report contains neither details of the recipe nor does Abraham apply the term “witch” to the young woman, the testimony can nevertheless be interpreted as an indication of the use “flying ointments” in the High Middle Ages.

The first doctor of the Late Middle Ages to write down a recipe for witches’ ointments was Johannes Hartlieb (* about 1400; † 1468), who was in the service of Duke Albrecht III of Wittelsbach and served him as an advisor and personal physician. Johannes wrote one of the earliest German herbal books around 1440 and in 1456 Das Buch aller verbotenen Künste (Original title: Das puch aller verpoten kunst, ungelaubens und der zaubrey). As this is the first known recording of a witch ointment (unguentum pharelis) recipe.

No childrens’fat is mentioned but animal fat (schmaltz von tieren) mixed with the blood of birds (Beimischung von Vogelblut). Hartlieb further associates the making of witches ointment with the prohibited act of Nigromancy or magic with the help of demons (Das alles ist recht Nigramancia (Nigromantie), und vast groß verboten ist). The complete text from Hartlieb’s book Das Buch aller verbotenen Künsteis, (chapter) 32 is reproduced here:

„Zu sölichem farn nützen auch man 19r und weib, nemlich die unhulden (Unholde, Hexen), ain salb die hayst unguentum pharelis. Die machen sy uß siben krewtern (Kräutern) und prechen yeglichs krautte an ainem tag, der dann dem selben krautt zugehört. Als am suntag prechen und graben sy Solsequium, am mentag Lunariam (Lunaria), am eretag (Dienstag) Verbenam (Verbena), am mittwochen Mercurialem (Mercurialis), am pfintztag (Donnerstag) Dachhauswurz Barbam jovis, am freytag Capillos Veneris (Capillus Veneris). Daruß machen sy, dann salben mit mischung ettlichs pluotz von vogel (unter Beimischung von Vogelblut), auch schmaltz von tieren; das ich als nit schreib, das yemant darvon sol geergert werden. Wann sy dann wöllen, so bestreichen sy penck (Bänke) oder stül, rechen oder ofengabeln und faren dahin. Das alles ist recht Nigramancia (Nigromantie), und vast groß verboten ist.“

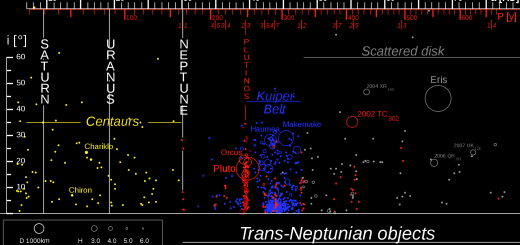

In Hartlieb’s recipe each plant is assigned astrologically to a weekday. Since the Middle Ages, the planetary symbols have also been used for weekdays. In alchemy, these symbols also stood for certain metals. The herbs in turn were assigned to planets. This allows 6 of the 7 herbs to be determined with certainty. However, the 7th herb was omitted “ich als nit schreib, das yemant darvon sol geergert werden” but one can confidently assume that this herb must have been the mandrake. Since this plant was attributed the greatest “magical properties”, it is a plant of Saturn (i.e. the missing Saturday), and the hallucinogenic effect makes a “flight experience” possible. The recipe could have looked like this:

Solsequium/Cichorium, Lunariam/Honesty, Verbenam/Verbena, Mercurialis/Mercuries, Dachhauswurz/Houseleeks(Sempervivum), Capillos Veneris/Venus hair fern, Mandrake, Bird’s Blood, Animal Lard). The herbs were probably dried, crushed and ground, and processed with the bird’s blood and animal lard to a paste.

Renaissance

In the Renaissance became a subject of discussion amongst clergymen as to whether witches were able physically to fly to the sabbath on their brooms with help of the ointment, or whether such ‘flight’ was explicable in other ways: a delusion created by the Devil in the minds of the witches; the souls of the witches leaving their bodies to fly in spirit to the Sabbath; or a hallucinatory ‘trip’ facilitated by the entheogenic effects of potent drugs absorbed through the skin.

An early proponent of the last explanation was Renaissance scholar and scientist Giambattista della Porta, who not only interviewed users of the flying ointment, but witnessed its effects upon such users at first hand, comparing the deathlike trances he observed in his subjects with their subsequent accounts of the bacchanalian revelry they had ‘enjoyed’. In connection with the question of witch ointments, reference is often made to the traditional recipes of his book Magiae naturalis sive de miraculis rerum naturalium (1558).

He reports of a witch’s “excursion” due to an ointment. The ointment recipe he wrote down mainly contains the hallucinogenic active ingredients of alkaloid-containing plants, also known as “witch herbs”, especially from the nightshade family, as well as more symbolic components (bat blood, etc.). Some scientific experiments carried out along Della Porta’s recipe at the beginning and middle of the 20th century proved the effectiveness of the ointment, but the characteristics of the reported noises were considered to be induced by the expectations of the researchers.

Dominican churchman Bartolommeo Spina (1465? / 1475? -1546) of Pisa gives two accounts of the power of the flying ointment in his Tractatus de strigibus sive maleficis (‘Treatise on witches or evildoers’) of 1525. The first concerns an incident in the life of his acquaintance Augustus de Turre of Bergamo, a physician. While studying medicine in Pavia as a young man, Augustus returned late one night to his lodgings (without a key) to find no one awake to let him in. Climbing up to a balcony, he was able to enter through a window, and at once sought out the maidservant, who should have been awake to admit him. On checking her room, however, he found her lying unconscious – beyond rousing – on the floor. The following morning he tried to question her on the matter, but she would only reply that she had been ‘on a journey’.

No authentic recipes are known from the witch trials. Rather, those accused of witchcraft knew the vegetable components of the ointment only from hearsay, or they would not have prepared the “Schmier” (as the flying ointment was also called) themselves, but would have received it according to their own statement from the devil personally. In 1545, Andrés de Laguna (1499-1560), who worked as a doctor at the court of Charles V, wrote that he had confiscated a witch ointment. The recipes handed down come from doctors and early scientists, which could explain why their composition corresponds to the medicines in use at the time. Gerolamo Cardano (1501-1576) described a witches’ ointment known as Lamiarum unguentum (“Lamia ointment”), which is said to have been composed of child fat, pressed celery juices, verbena and cinquefoil, as well as soot and ergot.

In Slovenia in 1689, Johann Weichard Freiherr von Valvasor reported in his work Die Ehre dess Hertzogthums Crain (Slava Vojvodine Kranjske) about an ointment that causes the witch to “dream of all the dancing, eating, drinking, music and the like, in other words that she thinks she has flown“. The recipe he handed down contains as active plants “Schlaff-Nachtschatten” (bittersweet nightshade) and “Wolffswurtz” (wolfsbane or aconite), both highly poisonous and intoxicating.

Witches ointments surviving in Norway in the 18the century

Northamptonshire Witches use a pig familiar as transport to visit a sick friend.

In the early 18th century, at the age of thirteen, a girl named Siri Jørgensdatter claimed that, when she was seven, her grandmother had taken her to the witches’ sabbath on the mountain meadow Blockula (‘blue-hill’): her grandmother led her to a pigsty, where she smeared a sow with some ointment which she took from a horn, whereupon grandmother and granddaughter mounted the animal and, after a short ride through the air, arrived at a building on the Sabbath mountain.

The sexual element attached to witches ointments

In his Quaestio de Strigis of 1470, Jordanes de Bergamo writes: the witches confess that…they anoint a staff and ride on it to the appointed place or anoint themselves under the arms and in other hairy places…[1] Bartolommeo Spina writes about the testimony of a certain notary of Lugano who, unable to find his wife one morning, searched for her all over their estate and finally discovered her lying deeply unconscious, naked and filthy with her vagina exposed wide open, in a corner of the pigsty. The notary ‘immediately understood that she was a witch’ and at first wanted to kill her on the spot, but, thinking better of such rashness, waited until she recovered from her stupor, in order to question her. Terrified by his wrath, the poor woman fell to her knees and confessed that during the night she had ‘been on a journey’.

Ecstatic witches rubbing ointments – Hans Baldung-Grien 1514

Some ointments and other psychotropics would be best absorbed through mucous membranes, and the traditional image of a female witch astride a broomstick implies the application of flying ointment to the vulva. Ergot, for example, is known to cause hallucinations and contractions of the uterus during the trance state. In the Middle Ages and Renaissance Ergot was rubbed indeed into the soft tissues of the vagina with a broomstick or other stick useful for the purpose.

A passage from the trial for witchcraft in Ireland of Hiberno-Norman noblewoman Alice Kyteler in 1324, while not explicit, certainly open to interpretations both drug-related and sexual: “…in rifleing the closet of the ladie [Alice Kyteler], they found a pipe of oyntement, wherewith she greased a staffe, upon which she ambled and galloped through thick and thin, when and in what manner she listed.”[2] It is also a very early account of such practices, pre-dating by some centuries witch trials in the early modern period.

The testimony of Dame Kyteler’s maidservant, Petronilla de Meath, while somewhat compromised by having been extracted under torture, contains references not only to her mistress’s abilities in the preparation of ‘magical’ medicines, but also her sexual behaviour, including at least one instance of (alleged) intercourse with a demon.

According to the inquisition (‘in which were five knights and numerous nobles’) set in motion by Richard de Ledrede, Bishop of Ossory, there was in the city of Kilkenny a band of heretical sorcerers, at the head of whom was Dame Alice Kyteler and against whom no fewer than seven charges relating to witchcraft were laid. The fifth charge is of particular interest in the context of the ‘greased staffe’ mentioned above:

In order to arouse feelings of love or hatred, or to inflict death or disease on the bodies of the faithful, they made use of powders, unguents, ointments and candles of fat, which were compounded as follows. They took the entrails of cocks sacrificed to demons, certain horrible worms, various unspecified herbs, dead men’s nails, the hair, brains, and shreds of the cerements of boys who were buried unbaptized, with other abominations, all of which they cooked, with various incantations, over a fire of oak-logs in a vessel made out of the skull of a decapitated thief.

Deducting from the above ingredients of purely symbolic significance relating to death and heresy, one is left with the cooking, in a fatty mixture, of ‘unspecified herbs’ and ‘horrible worms’ to produce, among other preparations, ‘unguents’ and ‘ointments’ – one of which was the ‘staffe-greasing’ ointment later found in the ‘pipe’ discovered in Dame Alice’s closet.

Notes:

[1] Bergamo, Jordanes de, Quaestio de Strigis (Unpublished manuscript, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris), quoted in Joseph Hansen Quellen und Untersuchen zur Geschichte des Hexenwahns und der Hexengefolgung im Mittelalter pps. 195-200. Pub. 1901 [1905]. Bonn : Carl Georgi.

[2] Wright, Thomas, ed. A Contemporary Narrative of the Proceedings Against Dame Alice Kyteler, Prosecuted for Sorcery in 1324, by Richard de Ledrede, Bishop of Ossory. London: The Camden Society, 1843.

You may also like to read:

Why did Witches Want to Ride their Broomsticks?

Herbs of the Devil

The incubus or succubus – nightmare or astral sex date?

Hecate – The Calling of the Crossroad Goddess

The Ancient Witch-Cult of The Basques

Walpurgis Night

Stefan Eggeler: Walpurgis Night witches, Kokain (Cocaine) and other illustrations

Witchcraft paintings – Dutch 17th century

Rosaleen Norton, Daughter of Pan

Mysteries of the Ancient Oaks

Black Cat Superstitions

The Mystical Mandrake

Little Secrets of the Poppy

Datura stramonium or jimson weed or zombi-cucumber

Mountain spirits

Wild Man or Woodwose

Sprite

Claude Gillot’s witches’ sabbat drawings