Walpurgis Night

Walpurgis Night is the night connecting the 30th of April to the 1st of May. This traditional feast mingles Saint Walpurgis with the arrival of Spring and what was supposed the most important witches sabbat of the year and in modern Wicca tradition it also conjoins with the revival of Beltane. Walpurgis Night or Walpurgisnacht is mainly a tradition of the northern European continent, especially Germany.

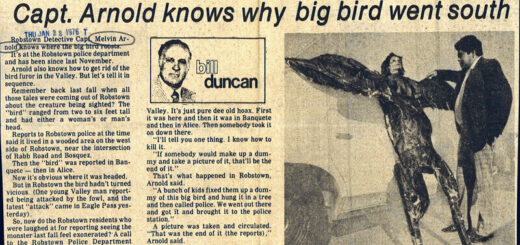

German postcard depicting Walpurgisnacht (walpurgis night) celebrated by witches in the Harz mountains

Walpurgis Night, an abbreviation of Saint Walpurgis Night (from the German Sankt Walpurgisnacht, also known as Saint Walpurga’s Eve, is the eve of the Christian feast day of Saint Walpurga, an 8th-century abbess in Francia, and is celebrated on the night of 30 April and the day of 1 May. This feast commemorates the canonization of Saint Walpurga (or Walburga) and the movement of her relics to Eichstätt, both of which occurred on 1 May 870.

Saint Walpurga was hailed by the Christians of Germany for battling “pest, rabies and whooping cough, as well as against witchcraft.” In Germanic folklore, Hexennacht, literally “Witches’ Night”, was believed to be the night of a witches’ meeting on the Brocken, the highest peak in the Harz Mountains, a range of wooded hills in central Germany between the rivers Weser and Elbe. Christians prayed to God through the intercession of Saint Walpurga in order to protect themselves from witchcraft, as Saint Walpurga was successful in converting the local populace to Christianity.

In parts of Christendom, people continue to light bonfires on Saint Walpurga’s Eve in order to ward off evil spirits and witches. Others have historically made Christian pilgrimages to Saint Walburga’s tomb in Eichstätt on the Feast of Saint Walburga, often obtaining vials of Saint Walburga’s oil.

Local variants of Walpurgis Night are observed throughout Europe in the Netherlands, Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovenia, Sweden, Norway, Lithuania, Latvia, Finland, and Estonia. In Denmark, the tradition with bonfires to ward off the witches is observed as Saint John’s Eve.

Saint Walpurga

The daughter of Saint Richard the Pilgrim and sister of Saint Willibald, Saint Walpurga (also known as Saint Walpurgis) was born in Devon, England in 710 A.D. Born into a prominent Anglo-Saxon family, Saint Walpurga studied medicine and became a Christian missionary to Germany, where she founded a double monastery in Heidenheim. As such, Christian artwork often depicts her holding bandages in her hand. As a result of Saint Walpurga’s evangelism in Germany, the people there converted to Christianity from heathenism. In addition, “the monastery became an education center and ‘soon became famous as a center of culture’.” Saint Walpurga was also known to repel the effects of witchcraft. Saint Walpurga perished in 777 and her tomb, to this day, produces holy oil (known as Saint Walburga’s oil), which is said to heal sickness; Benedictine nuns distribute this oil in vials to Christian pilgrims who visit Saint Walpurga’s tomb.

The celebration of Walpurgisnachton the Brocken in the Harz (Germany). Saint Walpurga is honoured for protection against witchcraft.

The current festival is named after the English Christian missionary Saint Walpurga (c. 710–777/9). As Saint Walpurga’s feast was held on 1 May (c. 870), she became associated with May Day, especially in the Finnish and Swedish calendars. The canonization of Saint Walpurga and the movement of her relics to Eichstätt occurred on 1 May in the year 870 thus leading to the Feast of Saint Walpurga and its eve, Walpurgis Night, being popularly observed on this date. When the bishop had Saint Walpurga’s relics moved, “miraculous cures were reported as her remains traveled along the route.” The eve of May Day, traditionally celebrated with dancing and bonfires to ward off witches, came to be known as Sankt Walpurgisnacht (“Saint Walpurga’s night”) in the German language.

The shortened name of the holiday is Walpurgisnacht in German, Valborgsmässoafton (“Valborg’s Mass Eve”) in Swedish, Vappen in Finland Swedish, Vappu in Finnish, Volbriöö in Estonian, Valpurgijos naktis in Lithuanian, Valpurģu nakts or Valpurģi in Latvian, čarodějnice and Valpuržina noc in Czech. In English, it is known as Saint Walpurga’s Night, Saint Walburga’s Night, Walpurgis Night, Saint Walpurga’s Eve, Saint Walburga’s Eve, the Feast of Saint Walpurga or the Feast of Saint Walburga.

The Germanic term Walpurgisnacht is recorded in 1668 by Johannes Praetorius as S. Walpurgis Nacht or S. Walpurgis Abend. An earlier mention of Walpurgis and S. Walpurgis Abend is in the 1603 edition of the Calendarium perpetuum of Johann Coler, who also refers to the following day, 1 May, as Jacobi Philippi, feast day of the apostles James the Less and Philip in the Western Christian calendar of saints.

The 17th-century German tradition of a meeting of sorcerers and witches on May Day eve (German: Hexennacht, Dutch: Heksennacht “Witches’ Night”) is influenced by the descriptions of Witches’ Sabbaths in 15th- and 16th-century literature.[citation needed] Given that witches gathered on this Hexennacht, the Western Christian Church established the Feast of Saint Walpurga on the same night in order to counteract witchcraft, given that the intercession of Saint Walpurga was efficacious against evil magic.

Across Christendom, people continue to light bonfires on Saint Walpurga’s Eve, now dedicated to this Christian saint, in order to ward off evil spirits and witches. Many Christians also make religious pilgrimages to Saint Walburga’s tomb in Eichstätt on Saint Walburga’s Day; in the 19th century, the number of pilgrims travelling to the Church of St. Walpurgis was described as “many thousand”

Beltane, Walpurgis Night in the British Isles

Beltane

In Lincolnshire Walpurgis Night was observed in rural communities until the second half of the 20th century, with a tradition of hanging cowslips to ward off evil. However, on the British Isles the night of April 30 – Mai 1 is all about Beltane. Beltane is the anglicised name for the Gaelic May Day festival. Most commonly it is held on 1 May, or about halfway between the spring equinox and the summer solstice.

Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. In Irish the name for the festival day is Lá Bealtaine, in Scottish Gaelic Là Bealltainn and in Manx Gaelic Laa Boaltinn or Boaldyn. It is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals—along with Samhain, Imbolc and Lughnasadh—and is similar to the Welsh Calan Mai.

Beltane is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature, and it is associated with important events in Irish mythology. It marked the beginning of summer and was when cattle were driven out to the summer pastures. Rituals were performed to protect the cattle, crops and people, and to encourage growth. Special bonfires were kindled, and their flames, smoke and ashes were deemed to have protective powers. The people and their cattle would walk around or jump over the bonfire or pass between two bonfires, and sometimes leap over the flames or embers. All household fires would be doused and then re-lit from the Beltane bonfire. These gatherings would be accompanied by a feast, and some of the food and drink would be offered to the aos sí.

Doors, windows, byres and the cattle themselves would be decorated with yellow May flowers, perhaps because they evoked fire. In parts of Ireland, people would make a May Bush: a thorn bush decorated with flowers, ribbons and bright shells. Holy wells were also visited, while Beltane dew was thought to bring beauty and maintain youthfulness. Many of these customs were part of May Day or Midsummer festivals in other parts of Great Britain and Europe.

Beltane celebrations had largely died out by the mid-20th century, although some of its customs continued and in some places it has been revived as a cultural event. Since the late 20th century, Celtic neopagans and Wiccans have observed Beltane, or something based on it, as a religious holiday. Neopagans in the Southern Hemisphere often celebrate Beltane at the other end of the year (around 1 November).

Pálení čarodějnic, Walpurgis Night in the Czech Republic

30 April is Pálení čarodějnic (“Burning of the witches”) or čarodějnice (“The witches”) in the Czech Republic. Huge bonfires up to 8 metres (26 ft) tall with a witch figure are built and burnt in the evening, preferably on top of hills. Young people gather around. Sudden black and dense smoke formations are cheered as “a witch flying away”. An effigy of a witch is held up and thrown into a bonfire to burn.

It is still a widespread feast in the Czech Republic, practiced since the pagan times. The feast is sometimes associated with Slavic goddess Marzanna, which represents winter and death.

As evening advances to midnight and fire is on the wane, it is time to go search for a cherry tree in blossom. This is another feast, connected with the 1st May. Young women should be kissed past midnight (and during the following day) under a cherry tree. They “will not dry up” for an entire year. The First of May is celebrated then as “the day of those in love”.

La nuit de Walpurgis – Constantin Nepo

Volbriöö, Walpurgis Night in Estonia

In Estonia, Volbriöö is celebrated throughout the night of 30 April and into the early hours of 1 May, where 1 May is a public holiday called “Spring Day” (Kevadpüha). Volbriöö is an important and widespread celebration of the arrival of spring in the country. Influenced by German culture, the night originally stood for the gathering and meeting of witches. Modern people still dress up as witches to wander the streets in a carnival-like mood.

The Volbriöö celebrations are especially vigorous in Tartu, the university town in southern Estonia. For Estonian students in student corporations (fraternities and sororities), the night starts with a traditional procession through the streets of Tartu, followed by visiting each other’s corporation houses throughout the night.

Vappu in Finland

In Finland, Walpurgis night (Vappu) (“Vappen”) is one of the four biggest holidays along with Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve, and Midsummer (Juhannus – Midsommar). Walpurgis witnesses the biggest carnival-style festival held in Finland’s cities and towns. The celebration, which begins on the evening of 30 April and continue on 1 May, typically centre on the consumption of sima, sparkling wine and other alcoholic beverages. Student traditions, particularly those of engineering students, are one of the main characteristics of Vappu.

Since the end of the 19th century, this traditional upper-class feast has been appropriated by university students. Many high school alumni wear the black and white student cap and many higher education students wear student coveralls. One tradition is to drink sima, a home-made low-alcohol mead, along with freshly cooked tippaleipä, funnel cakes in English.

In the capital, Helsinki, and its surrounding region, fixtures include the capping (on 30 April at 6 pm) of Havis Amanda, a nude female statue in Helsinki, and the biennially alternating publications of ribald matter called Äpy and Julkku, by engineering students of Aalto University. Both are sophomoric; but while Julkku is a standard magazine, Äpy is always a gimmick.

Classic forms have included an Äpy printed on toilet paper and a bedsheet. Often, Äpy has been stuffed inside standard industrial packages, such as sardine cans and milk cartons. For most university students, Vappu starts a week before the day of celebration. The festivities also include a picnic on 1 May, which is sometimes prepared in a lavish manner, particularly in Ullanlinnanmäki in central Helsinki. In Turku, it has become a tradition to cap the Posankka statue.

Vappu coincides with the socialist May Day parade. Expanding from the parties of the left, the whole of the Finnish political scene has adopted Vappu as the day to go out on stumps and agitate. This isn’t limited only to political activists; many institutions, such as the Lutheran Church of Finland, have followed suit, marching and making speeches. Left-wing activists of the 1970s still party on May Day. Carnivals are arranged, and many radio stations play leftist songs, such as The Internationale.

Traditionally, 1 May is celebrated by the way of a picnic in a park. For most, the picnic is enjoyed with friends on a blanket with food and sparkling wine. Some people arrange extremely lavish picnics with pavilions, white tablecloths, silver candelabras, classical music and extravagant food. The picnic usually starts early in the morning, where some of the previous night’s party-goers continue their celebrations from the previous night.

Some student organisations reserve areas where they traditionally camp every year. Student caps, mead, streamers and balloons have their role in the picnic and the celebration as a whole.

Valborg the Swedish Walpurgis Night

While the name Walpurgis is taken from the eighth-century English Christian missionary Saint Walburga, Valborg, as it is called in Swedish, also marks the arrival of spring. The forms of celebration vary in different parts of the country and between different cities. Walpurgis celebrations are not a family occasion but rather a public event, and local groups often take responsibility for organising them to encourage community spirit in the village or neighbourhood. Celebrations normally include lighting the bonfire, choral singing and a speech to honour the arrival of the spring season, often held by a local celebrity.

In the Middle Ages, the administrative year ended on 30 April. Accordingly, this was a day of festivity among the merchants and craftsmen of the town, with trick-or-treat, dancing and singing in preparation for the forthcoming celebration of spring. Sir James George Frazer in The Golden Bough writes, “The first of May is a great popular festival in the more midland and southern parts of Sweden. On the eve of the festival, huge bonfires, which should be lighted by striking two flints together, blaze on all the hills and knolls.”

Walpurgis bonfires are part of a Swedish tradition dating back to the early 18th century. At Walpurgis (Valborg), farm animals were let out to graze and bonfires (majbrasor, kasar) lit to scare away predators. In Southern Sweden, an older tradition, no longer practiced, was for the younger people to collect greenery and branches from the woods at twilight. These were used to adorn the houses of the village. The expected reward for this task was to be paid in eggs.

Faust Walpurgis Night

Choral singing is a popular pastime in Sweden, and on Walpurgis Eve virtually every choir in the country is busy. Singing traditional songs of spring is widespread throughout the country. The songs are mostly from the 19th century and were spread by students’ spring festivities. The strongest and most traditional spring festivities are also found in the old university cities, such as Uppsala and Lund, where undergraduates, graduates, and alumni gather at events that last most of the day from early morning to late night on April 30, or sista april (“The Last Day of April”) as it is called in Lund, or sista april as it is called in Uppsala. For students, Walpurgis Eve heralds freedom.

Traditionally the exams were over and only the odd lecture remained before term ends. On the last day of April, the students don their characteristic white caps and sing songs of welcome to spring, to the budding greenery and to a brighter future.

More modern Valborg celebrations, particularly among Uppsala students, often consist of enjoying a breakfast including champagne and strawberries. During the day, people gather in parks, drink considerable amounts of alcoholic beverages, barbecue, and generally enjoy the weather, if it happens to be favorable.

In Uppsala, since 1975, students honor spring by rafting on Fyris river through the center of town with rickety, homemade, in fact quite easily wreckable, and often humorously decorated rafts. Several nations also hold “Champagne Races” (Swedish: Champagnegalopp), where students go to drink and spray champagne or somewhat more modestly priced sparkling wine on each other. The walls and floors of the old nation buildings are covered in plastic for this occasion, as the champagne is poured around recklessly and sometimes spilled enough to wade in. Spraying champagne is, however, a fairly recent addition to the Champagne Race. The name derives from the students running down the downhill slope from the Carolina Rediviva library, toward the Student Nations, to drink champagne.

In Linköping many students and former students begin the day at the park Trädgårdföreningen, in the field below Belvederen where the city laws permits alcohol, to drink champagne breakfast in a similar way to Uppsala. Later at 15:00 o’clock the students and public gather at the courtyard of Linköping Castle. Spring songs are sung by the Linköping University Male Voice Choir, and speeches are made by representatives of the students and the university professors.

In Gothenburg, the carnival parade, The Cortège, which has been held since 1909 by the students at Chalmers University of Technology, is an important part of the celebration. It is seen by around 250,000 people each year. Another major event is the gathering of students in Garden Society of Gothenburg to listen to student choirs, orchestras, and speeches. An important part of the gathering is the ceremonial donning of the student cap, which stems from the time when students wore their caps daily and switched from black winter cap to white summer cap.

In Umeå, there is a tradition of having local bonfires. During recent years, however, there has been a tradition of celebrating Walpurgis at the Umeå University campus. The university organizes student choir songs, there are different types of entertainment and a speech by the president of the university. Different stalls sell hot dogs, candies, soft drinks, etc.

Heksennacht in the Netherlands

As in all Germanic countries, Walpurgisnacht was celebrated in areas of what is now the Netherlands. It has not been celebrated recently due to the national Koninginnedag (Queen’s Day) falling on the same date, though the new koningsdag (King’s Day) is on 27 April. The island of Texel celebrates a festival known as the ‘Meierblis [nl]’ (roughly translated as ‘May-Blaze’) on that same day, where bonfires are lit near nightfall, just as on Walpurgis, but with the meaning to drive away the remaining cold of winter and welcome spring. Occasional mentions to the ritual occur, and at least once a feminist called group co-opted the name to call for attention to the position of women (following the example of German women’s organizations), a variety of the Take Back the Night phenomenon.

Still, in recent years a renewed interest in pre-Christian religion and culture has led to renewed interest in Heksennacht (Witch’s Night) as well. In 1999, suspicions were raised among local Reformed party members in Putten, Gelderland of a Heksennacht festival celebrated by Satanists. The party called for a ban. That such a festival even existed, however, and that it was ‘Satanic’ was rejected by most others. The local Church in Dokkum, Friesland organized a Service in 2003 to pray for the Holy Spirit to, according to the church, counter the Satanic action.

You may also like to read:

Witches ointment

Why did Witches Want to Ride their Broomsticks?

Historical werewolf cases in Europe

The incubus or succubus – nightmare or astral sex date?

Hecate – The Calling of the Crossroad Goddess

The Ancient Witch-Cult of The Basques

Stefan Eggeler: Walpurgis Night witches, Kokain (Cocaine) and other illustrations

Witchcraft paintings – Dutch 17th century

Rosaleen Norton, Daughter of Pan

Mysteries of the Ancient Oaks

Black Cat Superstitions

The Mystical Mandrake

Little Secrets of the Poppy

Datura stramonium or jimson weed or zombi-cucumber

Mountain spirits

Wild Man or Woodwose

Sprite

Claude Gillot’s witches’ sabbat drawings

Sorceress

Sorceress

A Study of Witches and their Relations with Demons

by Jules Michelet

English

ISBN 9789492355249

Paperback

book size 148 x 210 mm

432 pages

€ 29,50

Sorceress (the English translation of La Sorcière) by Jules Michelet is still one of the most vivid, dark and confronting studies on witchcraft ever produced. Long before Murray, it positions the medieval witch within a diminishing ancient culture of nature worship and the ruthless efforts of Christianity – with its radical hostility towards nature and life – to overwrite it.

Michelet’s was an authority on the history of the Middle Ages, and his insistence that history should concentrate on ‘the people, and not only its leaders or its institutions’ placed him ahead of his time as a godfather of micro-history.

Starting in the 13th century the book moves on towards belladonna, the Sabbath and pacts with Satan, into the hells of the Burning Times – social contexts, church intrigues and mass hysteria always included. Via Basque witches, the Black Masses and demoniacal possessions we enter the satanic decadence of 17th century France, and finally the end of the witch burning era in 18th century, with the trial of Charlotte Cadière.

Though a solid work of history, the reader is not served a simple bone dry exposition of facts and theories, but something that tastes like a Bloody Mary.

Religion and Lust

or The Psychical Correlation of Religious Emotion and Sexual Desire

by James Weir Jr.

English

ISBN 9789492355270

Paperback

book size 148 x 210 mm

146 pages

€ 18,50

In Religion and Lust author James Weir Jr. (1856–1906), investigates the origins of religious feeling, the once world wide spread fertility worship and the physical correlation of religious emotion and sexual desire.

This publication is a revised edition of the 1905 version. It is unique, because a major part of the work is filled with a colourful collection of religious, or semi-religious, sexual rites, once practiced all over the globe, connecting the most “primitive” tribe to the most “civilized” nations. Some of them are really bizarre, like an extremely exhausting Pueblo masturbation-ritual, or the poring of wine over the phallus of a saint in France to make a medicine against barrenness.

The volume is also a rich source of fertility gods and hence it provides valuable data for pagans, occultists and Wiccans. The final section of the study deals with early 20th century sexology, gender-issues and related pathology, as studied in those days, and often in correlation with religious dogmas or taboos.