The real vampire in Russia and Slavonic countries

Vampire stories or stories of animated corpses were numerous in Russian and Slavonic folklore, all of them based on the same belief—that in certain cases the dead, in a material shape, leave their graves in order to destroy and prey upon the living. This belief is not peculiar to the Slavs but it is one of the characteristic features of their spiritual creed. Hence we know the Russian vampir, South-Russian upuir, anciently upir; Polish upior, Polish and Bohemian upir and Turkish Ubir. Supposed by some philologists to be from pit’ = drink, whence the Croatian name for a vampire pijawica.

The vampire is not limited to Transylvania, but the belief in returning dead is widespread in all Slavic countries.

Among races which burn their dead, little is known of regular “corpse-spectres.” Only vague apparitions, dream-like phantoms, are supposed, as a general rule, to issue from graves in which nothing more substantial than ashes has been laid. Is not certain that burial by cremation was universally practised by the heathen Slavs.

Author and researcher Kotlyarevsky, in his excellent work on their funeral customs, arrives at the conclusion that there never was any general rule on the subject, but that some Slavs buried without burning, while others first burned their dead, and then inhumed their ashes. But where it is customary to lay the dead body in the ground, “a peculiar half-life” becomes attributed to it by popular fancy, and by some races it is supposed to be actuated at intervals by murderous impulses.

In the East these are generally attributed to the fact of its being possessed by an evil spirit, but in some parts of Europe no such explanation of its conduct is given, though it may often be implied. “The belief in vampires is the specific Slavic form of the universal belief in spectres (Gespenster),” says Hertz, and certainly vampirism has always made those lands peculiarly its own which are or have been tenanted or greatly influenced by Slavs. See https://www.badische-zeitung.de/mysterioese-skelettfunde-friedhof-der-vampire for grave with decapitated vampire-skelettons.

Vampire belief in the Slavonic countries

But animated corpses often play an important part in the traditions of other countries. Among the Scandinavians and especially in Iceland, were they the cause of many fears, though they were not supposed to be impelled by a thirst for blood so much as by other carnal appetites, or by a kind of local malignity. In Germany tales of horror similar to the Icelandic are by no means unknown, but the majority of them are to be found in districts which were once wholly Lettic or Slavonic, though they are now reckoned as Teutonic, such as East Prussia, or Pomerania, or Lusatia.

But it is among the races which are Slavonic by tongue as well as by descent, that the genuine vampire tales flourish most luxuriantly: in Russia, in Poland, and in Servia—among the Czekhs of Bohemia, and the Slovaks of Hungary, and the numerous other subdivisions of the Slavonic family which are included within the heterogeneous empire of Austria.

Among the Albanians and Modern Greeks they have taken firm root, but on those peoples a strong Slavonic influence has been brought to bear. The Greeks, as they borrowed from the Slavonians a name for the Vampire, may have received from them also certain views and customs with respect to it. A number of passages from Hellenic writers prove that in ancient Greece spectres were frequently represented as delighting in blood, and sometimes as exercising a power to destroy.

The vampire in Greece

The Vampire is generally called in Greece by a name of Slavonic extraction; for in the islands, which were, little if at all affected by Slavonic influences, the Vampire bears a thoroughly Hellenic designation. The ordinary Modern-Greek word for a vampire, βουρκόλακας, he says, “is undoubtedly of Slavonic origin, being identical with the Slavonic name of the werwolf, which is called in Bohemian vlkodlak, in Bulgarian and Slovak, vrkolak, &c.,” the vampire and the werwolf having many points in common. Moreover, the Regular name for a vampire in Servian, he remarks, is vukodlak. This proves the Slavonian nature (die Slavicität) of the name beyond all doubt.

But the thirst for blood attributed by Homer to his shadowy ghosts seems to have been of a different nature from that evinced by the material Vampire of modern days, nor does that ghastly revenant seem by any means fully to correspond to such ghostly destroyers as the spirit of Gello, or the spectres of Medea’s slaughtered children. It is not only in the Vampire, however, that we find a point of close contact between the popular beliefs of the New-Greeks and the Slavonians.

Vampires in White Russia and the Ukraine

The districts of the Russian Empire in which a belief in vampires mostly prevails are White Russia and the Ukraine. But the ghastly blood-sucker, the Upir, whose name has become naturalized in so many alien lands under forms resembling our “Vampire,” disturbs the peasant-mind in many other parts of Russia, though not perhaps with the same intense fear which it spreads among the inhabitants of the above-named districts, or of some other Slavonic lands. The numerous traditions which have gathered around the original idea vary to some extent according to their locality, but they are never radically inconsistent.

Ghosts orbs or dust particles at the entrance of a cemetery.

Some of the details are curious. The Little-Russians hold that if a vampire’s hands have grown numb from remaining long crossed in the grave, he makes use of his teeth, which are like steel. When he has gnawed his way with these through all obstacles, he first destroys the babes he finds in a house, and then the older inmates. If fine salt be scattered on the floor of a room, the vampire’s footsteps may be traced to his grave, in which he will be found resting with rosy cheek and gory mouth.

The Turkish Ubir

Ubir (Chuvash: Вупăр (Vupăr) or Вупкăн (Vupkăn), Tatar: Убыр, Turkish: Ubır) is a mythological or folkloric being in Turkic mythology who subsist by feeding on the life essence (generally in the form of blood) of living creatures, regardless of whether it is undead person or being. Ubirs were usually reported as bloated in appearance, and ruddy, dark in colour; these characteristics were often attributed to the recent drinking of blood. The causes of vampiric generation were many and varied in original folklore. In Turkic and Slavic traditions, any corpse that was jumped over by an animal, particularly a dog or a cat, was feared to become one of the undead. Ubirs are reanimated corpses that kill living creatures to absorb life essence from their victims. Ubir or Ubar can also denote “witch”.

The Upir, someone who thrusts or bites

The word Ubir has parallels in virtually many Slavic languages: Czech and Slovak upír, and (perhaps East Slavic-influenced) upiór, Ukrainian упир (upyr), Russian упырь (upyr’), Belarusian упыр (upyr), from Old East Slavic упирь (upir’). The exact etymology is unclear. Among the proposed proto-Slavic forms are ǫpyrь and ǫpirь. Another, less widespread theory, is that the Slavic languages have borrowed the word from the Turkic term for Ubır or Ubar . Czech linguist Václav Machek proposes Slovak verb “vrepiť sa” (stick to, thrust into), or its hypothetical anagram “vperiť sa” (in Czech, archaic verb “vpeřit” means “to thrust violently”) as an etymological background, and thus translates “upír” as “someone who thrusts, bites”.

An early use of the Old Russian word is in the anti-pagan treatise “Word of Saint Grigoriy” (Russian Слово святого Григория), dated variously to the 11th–13th centuries, where pagan worship of upyri is reported.

Common Slavonic belief indicates a stark distinction between soul and body. The soul is not considered to be perishable. The Slavs believed that upon death the soul would go out of the body and wander about its neighbourhood and workplace for 40 days (compare the Tibetan belief of 40 days in Bardo prior to reincarnation) before moving on to an eternal afterlife. Thus pagan Slavs considered it necessary to leave a window or door open in the house for the soul to pass through at its leisure. During this time the soul was believed to have the capability of re-entering the corpse of the deceased. Much like the spirits mentioned earlier, the passing soul could either bless or wreak havoc on its family and neighbours during its 40 days of passing.

Upon an individual’s death, much stress was placed on proper burial rites to ensure the soul’s purity and peace as it separated from the body. The death of an unbaptized child, a violent or an untimely death, or the death of a grievous sinner (such as a sorcerer or murderer) were all grounds for a soul to become unclean after death. A soul could also be made unclean if its body were not given a proper burial. Alternatively, a body not given a proper burial could be susceptible to possession by other unclean souls and spirits. Slavs feared unclean souls because of their potential for taking vengeance.

From these deep beliefs pertaining to death and the soul derives the invention of the Slavic concept of Ubır. A vampire is the manifestation of an unclean spirit possessing a decomposing body. This undead creature needs the blood of the living to sustain its body’s existence and is considered to be vengeful and jealous towards the living. Although this concept of vampire exists in slightly different forms throughout Slavic countries and some of their non-Slavic neighbours, it is possible to trace the development of vampire belief to Slavic spiritualism preceding Christianity in Slavic regions. These applications are similar to the Turkish culture.

Horrifying gnawing

The Kashoubes (Polish Slavs of the Danzic region) say that when a Vieszcy, as they call the Vampire, wakes from his sleep within the grave, he begins to gnaw his hands and feet; and as he gnaws, one after another, first his relations, then his other neighbors, sicken and die. When he has finished his own store of flesh, he rises at midnight and destroys cattle, or climbs a belfry and sounds the bell. All who hear the ill-omened tones will soon die. But generally he sucks the blood of sleepers. Those on whom he has operated will be found next morning dead, with a very small wound on the left side of the breast, exactly over the heart.

The Lusatian Wends hold that when a corpse chews its shroud or sucks its own breast, all its kin will soon follow it to the grave. The Wallachians say that a murony—a sort of cross between a werwolf and a vampire, connected by name with our nightmare—can take the form of a dog, a cat, or a toad, and also of any blood-sucking insect. When he is exhumed, he is found to have long nails of recent growth on his hands and feet, and blood is streaming from his eyes, ears, nose and mouth.

How to end vampire attacks

The Russian stories give a very clear account of the operation performed by the vampire on his victims. Thus, one night, a peasant is conducted by a stranger into a house where lie two sleepers, an old man and a youth. “The stranger takes a pail, places it near the youth, and strikes him on the back; immediately the back opens, and forth flows rosy blood. The stranger fills the pail full, and drinks it dry. Then he fills another pail with blood from the old man, slakes his brutal thirst, and says to the peasant, ‘It begins to grow light! let us go back to my dwelling.’”

Many skazkas also contain, as we have already seen, very clear directions how to deprive a vampire of his baleful power. According to them, as well as to their parallels elsewhere, a stake must be driven through the murderous corpse. In Russia an aspen stake is selected for that purpose, but in some places one made of thorn is preferred. But a Bohemian vampire, when staked in this manner in the year 1337, says the German folklorist Wilhelm Mannhardt, merely exclaimed that the stick would be very useful for keeping off dogs; and a strigon (or Istrian vampire) who was transfixed with a sharp thorn cudgel near Laibach, in 1672, pulled it out of his body and flung it back contemptuously. The only certain methods of destroying a vampire appear to be either to consume him by fire, or to chop off his head with a grave-digger’s shovel. The Wends say that if a vampire is hit over the back of the head with an implement of that kind, he will squeal like a pig.

The origin of the Vampire

The origin of the Vampire is hidden in obscurity. In modern times it has generally been a wizard, or a witch, or a suicide, or a person who has come to a violent end, or who has been cursed by the Church or by his parents, who takes such an unpleasant means of recalling himself to the memory of his surviving relatives and acquaintances.

But even the most honorable dead may become vampires by accident. He whom a vampire has slain is supposed, in some countries, himself to become a vampire. The leaping of a cat or some other animal across a corpse, even the flight of a bird above it, may turn the innocent defunct into a ravenous demon. Sometimes, moreover, a man is destined from his birth to be a vampire, being the offspring of some unholy union. In some instances the Evil One himself is the father of such a doomed victim, in others a temporarily animated corpse.

But whatever may be the cause of a corpse’s “vampirism,” it is generally agreed that it will give its neighbors no rest until they have at least transfixed it. What is very remarkable about the operation is, that the stake must be driven through the vampire’s body by a single blow. A second would restore it to life. This idea accounts for the otherwise unexplained fact that the heroes of folk-tales are frequently warned that they must on no account be tempted into striking their magic foes more than one stroke. Whatever voices may cry aloud “Strike again!” they must remain contented with a single blow.

Adapted for blog from :Russian Fairy Tales – A choice collection of Muscovite folk-lore by W. R. S. Ralston, M. A.

See also:

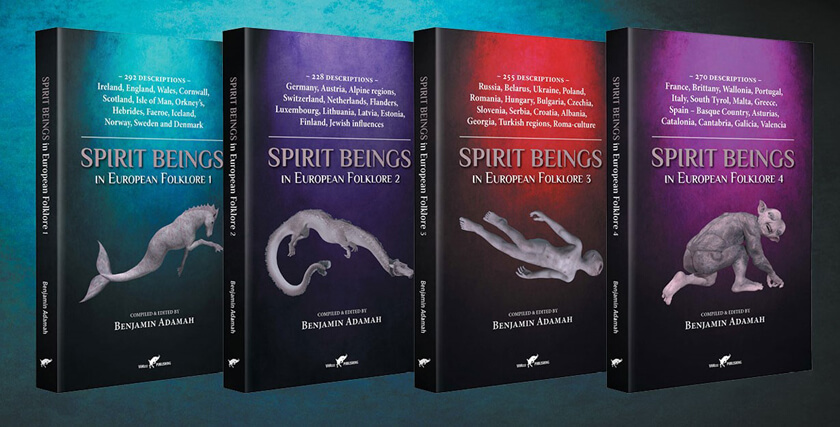

Spirit Beings in European Folklore

The banshee

Historical werewolf cases in Europe

Poltergeist

The incubus or succubus – nightmare or astral sex date?

Aura protection – How to protect your energy field from negative influences

Mountain spirits

The Mysterie of the White Ladies

Wild man or Woodwose

Black cat superstitions

Sex and Mediumship – quotations on the observation of ectoplasma

Allan Kardec -Life after death as a science…

Aura Colors – What do they mean?

Thirty Years among the Dead

animal ghosts and apparitions

Black dog apparitions

Thought forms – Thoughts condensed on purpose or by accident

Top 7 techniques for inducing an Out of Body Experience (OBE)