Mysteries of the Ancient Oaks

Once upon a time vast areas of Europe were covered in dense and ancient oak forests. A major part of Celtic France was oak forest before the Romans systematically started cutting the oaks down, causing one of the first environmental disasters of our history. This was not just for timber. It also had a political motive.

Within the native European cultures of the Celts and the Germanic tribes, the oak was a holy tree, and therefore the mysteries of the oaks were closely intermingled with their religious beliefs. Especially for the Gaelic population of France, where the Oak forests were sacred to the Druidic leaders, who worshipped the Tree Mothers, and were a menace in the eyes of the Roman invader. Cutting their forests was thus part of hitting them in the very heart of their culture and identity. Many Druids left France with the disappearing of the oak forests and took sanctuary on the British Isles.

The Oak and the Thunder god

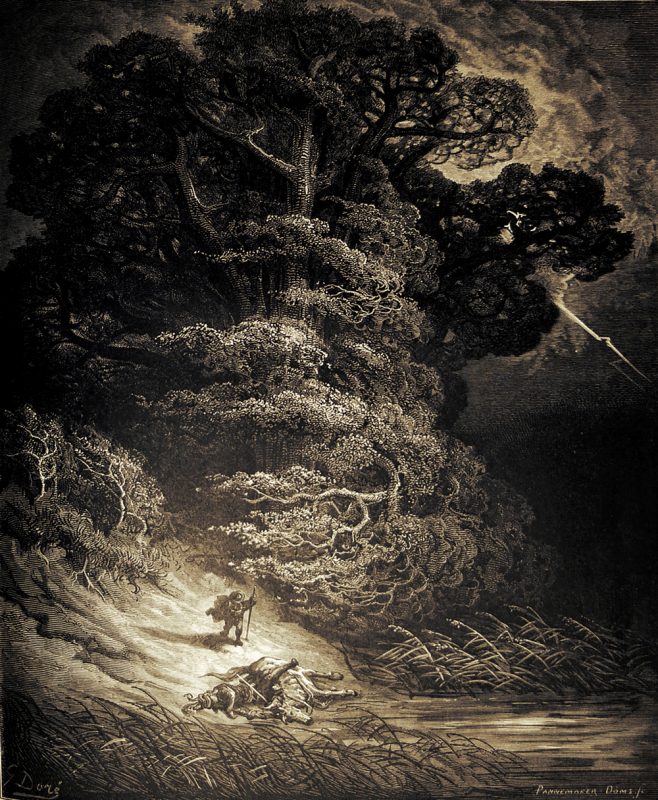

Oak mythology is very old. In the Orphic religion, which can be traced back to the 6th century BC, we find the Huptopteros Drus, the Goddess (Persephone) symbolized by a holy oak that is being enwrapped in the creation flow by Zos, (a primordial Zeus).

In the pre-Christian religion of Europe it was believed that the wood spirits or Dryads favoured the oak among all other trees. The Goddess Brigid, apart from groves and springs, was also associated with the oak tree, and so was Diana, whose holy oak at Lake Nemi was guarded by a spirit known as Rex Nemorensis. The oak grove at Dodona was sacred to Zeus. In Baltic and Slavic mythology, the oak is the sacred tree of Latvian Pērkons, Lithuanian Perkūnas, Prussian Perkūns and Slavic Perun, the god of thunder and one of the most important deities in the Baltic and Slavic pantheons. In the Norse and Germanic mythology the oak was sacred to the Thunder god Thor/Donar.

Oaks are most often struck by lightning than other trees and are sacred to the Thunder Gods in many European pre-Christian religions.

https://vamzzz.com/product/plant-lore-legends-lyrics/

In Celtic polytheism, the name of the oak tree was part of the Proto-Celtic word for ‘druid’ derwo-weyd, druwid; however, Proto-Celtic derwo- (and dru-) can also be adjectives for ‘strong’ and ‘firm’, so Ranko Matasovic interprets that druwid- may mean ‘strong knowledge’. As in other Indo-European faiths, Taranis, being a thunder god, was associated with the oak tree. The Indo-Europeans worshipped the oak and connected it with a thunder or lightning god; “tree” and drus may also be cognate with “Druid,” the Celtic priest to whom the oak was sacred. There has even been a study that shows that oaks are more likely to be struck by lightning than any other tree of the same height.

The Oak King

One feature of oaks mythology is the legendary Pērkons, Lithuanian Perkūnas, Prussian Perkūns and Slavic Perun, who some fifty years back made his revival in Wicca and Neopaganism, and his counterpart the Holly King are variables of the Green Man or Wild Man archetype. Found in many cultures for many ages around the world, the Green Man is often related to natural vegetative deities. It is primarily interpreted as a symbol of rebirth, representing the cycle of growth each spring.

In his book The White Goddess, the author Robert Graves proposed that the mythological figure of the Holly King represents one half of the year, while the other is personified by his counterpart and adversary the Oak King: the two battle endlessly as the seasons turn. At Midsummer the Oak King, representing the light and fertile half of the year, is at the height of his strength, while the Holly King, representing the dark, or regenerating half, is at his weakest. The Holly King begins to regain his power, and at the Autumn Equinox, the tables finally turn in the Holly King’s favour; his strength peaks at Midwinter.

A similar idea was suggested previously by Sir James George Frazer in his work The Golden Bough in Chapter XXVIII, The Killing of The Tree Spirit in the section entitled The Battle of Summer and Winter. Frazer drew parallels between the folk-customs associated with May Day or the changing seasons in Scandinavian, Bavarian and Native American cultures, amongst others, in support of this theory. However the Divine King of Frazer was split into the kings of winter and summer in Graves’ work. These pairs are seen as the dual aspects of the male Earth deity, one ruling the waxing year, the other ruling the waning year. Wiccan pioneers Stewart and Janet Farrar, following Graves’ theory, gave a similar interpretation to witchcraft related seasonal rituals. ♦

© 2017 Benjamin Adamah

https://vamzzz.com/product/giants-and-dwarfs/

You may also like to read:

Witches ointment

Why did Witches Want to Ride their Broomsticks?

The incubus or succubus – nightmare or astral sex date?

Hecate – The Calling of the Crossroad Goddess

The Ancient Witch-Cult of The Basques

Walpurgis Night

Stefan Eggeler: Walpurgis Night witches, Kokain (Cocaine) and other illustrations

Witchcraft paintings – Dutch 17th century

Rosaleen Norton, Daughter of Pan

Black Cat Superstitions

The Mystical Mandrake

Little Secrets of the Poppy

Datura stramonium or jimson weed or zombi-cucumber

Mountain spirits

Wild Man or Woodwose

Sprite

Claude Gillot’s witches’ sabbat drawings