Wild Man or Woodwose

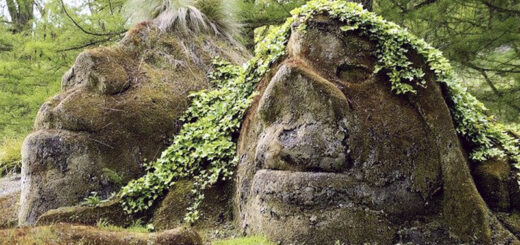

The Wild Man is an anthropomorphic being in the popular beliefs of the Germanic and Slavic linguistic area from the early Middle Ages to the beginning of modern times. He was described or portrayed as a loner, endowed with giant powers, strongly hairy, naked or only with moss or foliage clothed primitive man. His way of life was considered, on the one hand semi-animal and primitive, but on the other hand also paradisaical and close to nature. Uninhabited or uninhabitable forest and mountain areas were considered his preferred place of residence.

Wild man appears in Two scenes from Der_Busant (1480-1490)

A common Middle English term for the wild man was woodwose or wodewose (also spelled woodehouse, wudwas). Wodwos occurs in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (c. 1390).The Middle English word is first attested for the 1340s, in references to the “wild man” decorative artwork popular at the time, in a Latin description of an embroidery of the Great Wardrobe of Edward III, but as a surname it is found as early as 1251, of one Robert de Wudewuse. In reference to an actual legendary or mythological creature, the term is found during the 1380s, in Wycliffe’s Bible, translating שעיר (LXX δαιμόνια, Latin pilosi meaning “hairy”) in Isaiah 13:21 The occurrences in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight date to soon after Wycliffe’s Bible, to c. 1390.

Wild Man design for a Stained Glass Window by Hans Holbein the Younger

Etymology of woodwose

The first element of woodwose is usually explained as from wudu “wood”, “forest”, derived from the Proto-Germanic widuz “woodland”, “wood”, “tree”. The second element is less clear. It has been identified as a hypothetical noun *wāsa “being”, from the verb wesan, wosan “to be”, “to be alive”. The Old English form is unattested, but it would have been *wudu-wāsa or *wude-wāsa. It may also mean a forlorn or abandoned person, cognate with the German Waise and Dutch wees which both mean “orphan.” Old High German had the terms schrat, scrato or scrazo, which appear in glosses of Latin works as translations for fauni, silvestres, or pilosi, identifying the creatures as hairy woodland beings. Some of the local names suggest associations with characters from ancient mythology. Common in Lombardy and the Italian-speaking parts of the Alps are the terms salvan and salvang, which derive from the Latin Silvanus, the name of the Roman tutelary god of gardens and the countryside. Similarly, folklore in Tyrol and German-speaking Switzerland into the 20th century included a wild woman known as Fange or Fanke, which derives from the Latin fauna, the feminine form of faun. Medieval German sources give as names for the wild woman lamia and holzmoia; the former clearly refers to the Greek wilderness demon Lamia while the latter derives ultimately from Maia, a Greco-Roman earth and fertility goddess who is identified elsewhere with Fauna and who exerted a wide influence on medieval wild-man lore. Slavic has leshy “forest man”.

Other wild men in Europe

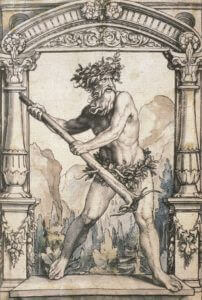

Wild man holding shield by Martin Schongauer 1470-90

Various languages and traditions include names suggesting affinities with Orcus, a Roman and Italic god of death. For many years people in Tyrol called the wild man Orke, Lorke, or Noerglein, while in parts of Italy he was the orco or huorco. The French ogre has the same derivation, as do modern literary orcs. Importantly, Orcus is associated with Maia in a dance celebrated late enough to be condemned in a 9th- or 10th-century Spanish penitential. The Basques had their Basajaun, an important figure in Basque mythology.

Wild men are a specifically Central European form of a mythical idea of semi-human forest dwellers that occurs worldwide in all cultures. These creatures first appear as wild people (medieval Latin silvani) or wild people, later personified as wild man and wild woman or also as wild lady:

“The various views of forest men and wild men, which have grown out of customs and literature, have condensed in the visual arts into the representation of a wild, hairy, often loinclothed human being. These beings, who in the literal translation illustrate the wild, include all versions of these mythical figures. This characterization persists through all stylistic epochs.”

In the texts and representations, the Wild Man often has a metaphorical meaning. He stands for the wild, the threatening nature, for the overcoming of nature, for outdated cultural development stages of man and for certain character characteristics of men which are perceived as primeval. In the Middle Ages, the Wild Man was transformed from a myth of popular belief, an archetype of chaos, to a symbol of desirable character traits in the stories of the upper class.

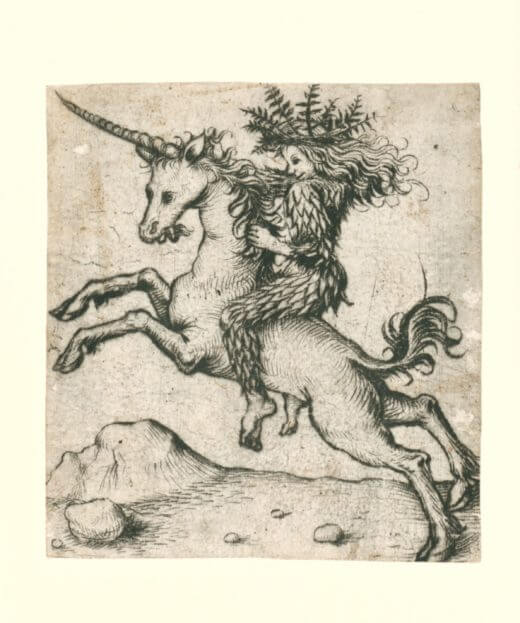

Wild men on a unicorn – Meester van het Amsterdamse Kabinet 1473-1477

Appearances of wild men

Wild men, and more rarely wild women, appear in legends, fairy tales and medieval literature, since the middle of the 14th century in emblematic representations of medieval art on tapestries, miniature boxes, choir stalls, reliquary boxes, tiles, glass paintings, graphics, as a sign in card games, as a common figure or more often as a shield holder in coats of arms, as coin pictures, as a house sign and as a man figure in half-timbered houses, as a figure in processions, festivals and rituals, depicted by a disguised human being, as eponym for parcels and mountains, for mining facilities such as mines and galleries, for mining towns and later also for gastronomic facilities such as hotels and restaurants, as a metaphor for certain characteristics of man and man, and especially in the international literature of the 1980s as a metaphor for aspects of the gender role of men in redefining the distribution of gender roles in the course of social upheaval.

Features & Benefits

Especially in the archaic legends of the Alps (mainly Tyrol) do wild men have certain characteristics of ghosts and nature demons. Basajaun and the offspring of Sylvanus are also nature deamons. In most cases however wild men are human beings and not transcendent beings, i.e. they are not beings from another world, for example the divine world, who materialize arbitrarily in this world and appear in different forms and can disappear again. Since wild men are not able to do this, they can also be captured by man. Wild men have superhuman abilities, sometimes something like magic powers or visionary abilities, but they are even biological beings that are vulnerable, can be shot at and hurt. They can have a sexual and family life.

Wild people, in the margins of a late 14th-century Book of Hours

Wild men are human

Wild men are also human beings, not animal beings. Apart from their intensive hair growth (hypertrichosis), their great physical strength and nakedness, which can also occur in normal people, they have no animal characteristics. They have no hoves, no tail and no horns. On representations and in the narratives, the wild man is always barefoot and – unlike animals – armed with a club or a torn tree.

Wild men are usually inferior to humans when their great physical strength is rendered harmless. This can happen through sexual seduction, but also through female virtue, through alcohol, through magic, through combat with professional military training and armament, through long-range weapons or through other particularly intelligent measures. They can then be locked up and kept in cages like animals, prisoners or lunatics. The expectations of getting to the bottom of the mystery of their savagery, however, are fundamentally disappointing.

Only at the beginning of modern times did the wild men become guardians of mostly metal treasures (a role that had previously rather been ascribed to the magical and technologically superior dwarfs). This was the time when humans had to systematically open up the last uninhabited areas of the Middle Ages in order to access the mineral resources that were waiting to be discovered in the mountains, which had previously been avoided as inhospitable and wild. Here they encountered the savagery of nature, from which they were able to take away its treasures by previously unknown methods. Typically it is here for the first time also miners encounter the wild man. Something which had been the privilege of hunters for centuries.

The wild man and the “Neanderthal-memory”

It is no longer possible to reconstruct whether the ideas of the Wild Man spread all over the world have preserved old memories of the times when several species of hominini still existed side by side. Although modern humans (Homo sapiens) and Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) have lived in the immediate vicinity of Central Europe for about 10,000 years and, at least in a certain time window before the splitting up in the Eurasian populations, also produced common offspring, which can be proven in the genetic material of the Eurasian populations living today. However, due to the large time gap between the extinction of the last Neanderthals 30,000 – 25,000 years ago and the first written figure of a wild man in the Gilgamesh epic more than 20,000 years later, no verifiable connection can be established. This is all the more true for the distribution of the wild man-theme in early medieval to modern Europe.

The wild man in the bible and Christianity

Albrecht Durer – Woodwoses 1499

Some references in the Old Testament speak in favour of the explanation that the stories of the Wild Man are based on the transitional period from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic, when people developed from hunters and gatherers to farmers and cattle breeders. The old biblical stories have a certain significance here, as they come from the area where agriculture was first developed. Genesis 2:5-33 deals with the dispute between the twin brothers Esau, the older, instinctive, hairy, hunter, and Jacob, the younger, self-conscious, fine-skinned, urban, intellectual, cultivated favorite son of mother Rebekah. The competition between agriculture and hunting shows the superiority of the new form of society: The hunter Esau must sell his right of inheritance to his brother Jakob, who is agriculturally active and thus economically superior, in order to have anything to eat at all. Jacob, the chosen one of God, thus became the progenitor of the twelve tribes of Israel. The hairy Esau went away empty-handed and became the progenitor of a mountain people.

In the ancient legends of the alpine region, wild men depicted, among other things, nature, which was difficult to tame and unpredictable, and which made it particularly difficult for people in inhospitable regions to cope with industrialization. Man felt defenseless to the forces and personified them in a series of mythical figures, including the Wild Men (e.g. in Wildon, Styria).

In Christianity, wild men stand outside creation and the plan of salvation. They are figures of the lower mythology, which serve in the ecclesiastical understanding to symbolize the virtuous victory over them and thus over the wild, the lower and the vicious. In the imagination of medieval man, anything “wild” was considered to be that which stood outside human culture, community, custom and norm. Moreover, it was considered the desert and the undeveloped, the confused and the disastrous. For this reason, the Wild Men often appear in the late Middle Ages on Fastnacht (Shrove Tuesday), when, together with the other fools, they represent the representatives of the distance from God and thus of the devil. As these representatives the Wild Man and the Wild Woman can be seen together with the fool and the devil on a vaulted console of the Holy Cross Minster in Rottweil.

The courtly literature of the Middle Ages contrasted the knights, who were regarded as social role models, with various fright figures to show their ethical and militant superiority. These figures included not only dragons and giants but also wild men.

At the beginning of the early modern era, the aspect emerged that the overcoming of nature, here in the form of the Wild Man, also opened up opportunities for wealth for mankind. The opening up of inhospitable regions by the courageous advance of the miners was linked with legends of the overcoming of wild men who guarded metal mineral resources. This led to the use of the Wild Man motif on coins and coats of arms. They thus became a symbol of the wealth gained from nature and are still proudly presented today.

Similar phenomena

Forest and mountain spirits

Forest and mountain spirits in the broadest sense appear in legends and fairy tales throughout Europe and beyond. These creatures are depicted as much more powerful than the Wild Man. They are regarded as masters of nature and can be influenced by man, but not destroyed. The Schrat seems to be similar to the Wild Man in many respects. In the Riesengebirge (Giant Mountains) the Rübezahl is at home. In Scandinavia the Skogsfru haunts the mountains. These are ghostly creatures that can appear in various forms. They are able to transform and simply disappear. They usually have magical powers or the power of nature. Rübezahl is considered the lord of the mountains. He can cause thunderstorms to which man is then helplessly exposed. Although there are stories in which he is tricked by man, one cannot catch and imprison Rübezahl (see also: Mountain Spirit).

The insane or outcast

In old stories, for example in the Bible or in medieval poetry, there are reports of people who, due to an accident or a punishment from God, have fallen into madness and have to live wild like an animal without reason. This may include tearing off their clothes and running naked into the wilderness. Outcasts, confused and lost people are depicted similarly to wild men, but in contrast to them crawling on all fours.

Such a punishment is imposed on the figure of Nebuchadnezzar from the report in Dan 4,1-34. Nebuchadnezzar is an arrogant tyrant who persecutes the Jews. A heavenly voice announces the deepest humiliation to him. He falls into madness and has to live like an animal and eat grass for seven years. In the Welsh Merlin legend and the Latin Vita Merlini based on it, the poet Myrddin meets such a fate: When his master is killed in a battle, he loses his mind, runs into the woods and speaks there to an apple tree and the pigs. So he lives 50 years until he is healed by a miracle spring.

A haunting description can also be found as the central plot turn in the Middle High German Arthurian novel Iwein by Hartmann von Aue. The Arthurian knight Iwein misses a deadline set by his wife and thus loses her favour. Thereupon he flees from the court, becomes a raving addict and ekes out his life in the woods as an undressed madman:

dô wart sîn riuwe alsô grôz

daz im in daz hirne schôz

ein zorn unde ein tobesuht,

er brach sîne site und sîne zuht

und zarte abe sîn gewant,

daz er wart blôz sam ein hant.

sus lief er über gevilde

nacket nâch der wilde.

(Freely translated: Then his remorse became so great that anger and raving madness shot into his brain. He forgot decency and upbringing, pulled his robe off his body until he was completely exposed. So he ran naked across the sunny fields into the wilderness.)

Medieval Epic

The fight in the forest with wild man – Hans Burgkmair the Elder (1473–1531)

The figure of the wild man appears frequently in the profane literature of the Middle Ages. We find early examples (as Schrat) already in Old High German glosses, since the 11th century, here with Burchard of Worms, for the first time, the wild woman is mentioned. Heinrich von Hesler describes them as people living in forests, waters, caves and mountains. Chrétien de Troyes, in “Le Chevalier au Lion ou le roman d’Yvain”, around 1170, writes about the knightly title hero who temporarily hanges into a wild man, and can only be “cured” by the lady of his heart. In the Arthur novel Wigalois a wild woman is described. In other courtly novels, too, the Wild People with their rough, unbridled nature form a counter-world to courtly life.

In the medieval epics of the hero Dietrich von Bern it is reported how the hero fights with different mythical figures – giants and dragons. In the story Der jüngere Siegenott, he also meets a wild man who has captured a dwarf. The dwarf calls Dietrich for help because he fears that the Wild Man wants to kill him. He calls him tiufel (devil). Dietrich fights against the Wild Man, but his sword cannot penetrate his fur-like hair, which looks like armor. Then he tries to strangle the Wild Man, which doesn’t work either. Finally, he can defeat him by means of a spell provided to him by the dwarf. It turns out that the Wild Man can speak. He willingly gives Dietrich further tips to help him overcome his arch-enemy, the giant Siegenot.

Wild children

Wolf children or wild children are children, often foundlings, who grew up isolated from humans for a while at a young age and therefore differ in their learned behaviour from children who grew up normally. In rare cases, wolf children were adopted by animals and lived with them.

There are many stories and legends about wolf children, but scientists have only been able to study a few real cases. Since the middle of the 14th century at least 53 wild children have been found.

In the documented cases, the integration of these children into human society was not particularly successful (e.g. Victor von Aveyron, Kaspar Hauser).

Disregarding these historical experiences, fabulous heroes are often said to have a childhood outside of human civilization, as if that were a prerequisite for superhuman achievements. In Roman mythology, Romulus and Remus are suckled by a she-wolf, a very popular motif in European and Oriental mythology, as similar stories are reported by the Slovakian warriors Waligor and Wyrwidub, by the founder of the Old Persian Empire, Kyros, and by the legendary hero Dietrich von Bern in Germanic mythology. Also the biblical Moses was hidden for a while in the reed thicket before he was found and could enjoy a special education.

You may also like to read:

Witches ointment

Historical werewolf cases in Europe

Why did Witches Want to Ride their Broomsticks?

The incubus or succubus – nightmare or astral sex date?

Hecate – The Calling of the Crossroad Goddess

The Ancient Witch-Cult of The Basques

Walpurgis Night

Stefan Eggeler: Walpurgis Night witches, Kokain (Cocaine) and other illustrations

Witchcraft paintings – Dutch 17th century

Rosaleen Norton, Daughter of Pan

Mysteries of the Ancient Oaks

Black Cat Superstitions

The Mystical Mandrake

Little Secrets of the Poppy

Datura stramonium or jimson weed or zombi-cucumber

Mountain spirits

Sprite

Claude Gillot’s witches’ sabbat drawings