Anansi, Spider God and Freedom Symbol

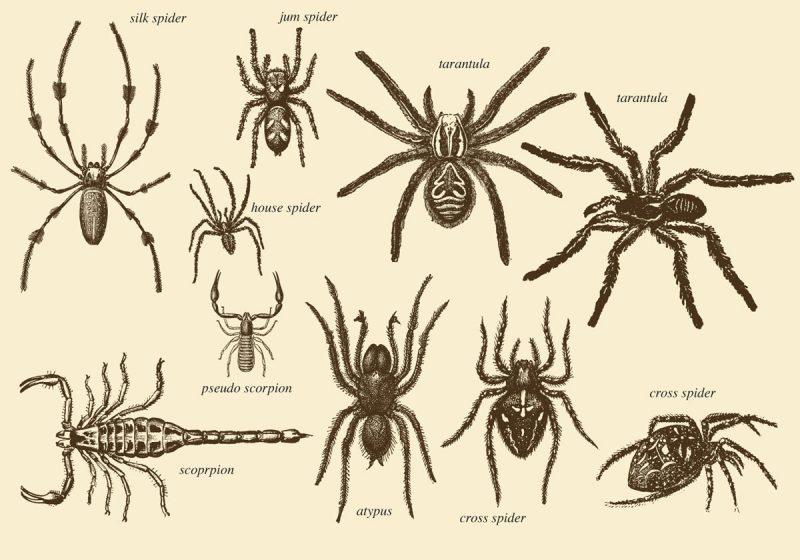

Anansi is both a god, spirit and African folktale character. He often takes the shape of a spider and is considered to be the spirit of all knowledge of stories. He is also one of the most important characters of West African and Caribbean folklore.

Anansi the African an Afro-Caribbean spider-god is a symbol of cunningness and freedom

Anansi as a spirit, acts on behalf of Nyame, his father and the Sky Father. He brings rain to stop fires and performs other duties for him. His mother is Asase Ya. According to some stories his wife is known as Miss Anansi or Mistress Anansi, but most commonly as Aso. Anansi is depicted in many different ways. Sometimes he seems like an ordinary spider, sometimes he is a spider wearing clothes or with a human expression and sometimes he seems much more like a human with spider elements, such as eight legs.

In some beliefs, the spider god is responsible for creating the sun, the stars and the moon, as well as teaching mankind the techniques of agriculture. Other names for Anansi are Ananse, Kwaku Ananse, and Anancy. In the southern United States, he has evolved into Aunt Nancy.

The spider god tales originated from the Ashanti people of present-day Ghana. The word Ananse is Akan and means “spider”. They later spread to other Akan groups and then to the West Indies, Suriname, Sierra Leone (where they were introduced by Jamaican Maroons) and the Netherlands Antilles. On Curaçao, Aruba and Bonaire he is known as Nanzi, and his wife as Shi Maria.

Anansi tales are some of the best-known amongst the Asante people of Ghana. The stories made up an exclusively oral tradition, and indeed Anansi himself was synonymous with skill and wisdom in speech. It was as remembered and told tales, that they arrived in the Caribbean and other parts of the New World, with captives via the Atlantic slave trade.

In the Caribbean Anansi is often celebrated as a symbol of slavery resistance and survival.

In the Caribbean version is often celebrated as a symbol of slavery resistance and survival. Anansi is able to turn the table on his powerful oppressors using his cunning and trickery, a model of behaviour utilised by slaves to gain the upper-hand within the confines of the plantation power structure.

Anansi is also believed to have played a multi-functional role in slaves’ lives, as well as inspiring strategies of resistance the tales enabled slaves to establish a sense of continuity with their African past and offered them the means to transform and assert their identity within the boundaries of captivity. Stories of Anansi became such a prominent and familiar part of the Ashanti oral culture that the word Anansesem—“spider tales”— came to embrace all kinds of fables. Elsewhere these spider-tales have other names, for instance Anansi-Tori in Suriname, Anansi in Guyana, and Kuent’i Nanzi in Curaçao. The Jamaican versions of these stories are the most well preserved, because Jamaica had the largest concentration of Asante as slaves in the Americas.

Martha Warren Beckwith, author of Anansi

Martha Warren Beckwith

Martha Warren Beckwith (January 19, 1871 – January 28, 1959) was an American folklorist and ethnographer and philosopher. She was born in Wellesley Heights, Massachusetts. In 1920, Martha Beckwith became the first person to hold a chair in Folklore at any college or university in the country.

The Folklore Foundation, established at Vassar, with a donation by the naturalist Annie Alexander, was an unprecedented institution. With its establishment, Vassar College suddenly became a centre of research in the almost entirely new field of folk culture, while Martha Beckwith had a major part in emancipating the general attitude towards folklore studies in the first half of the twentieth century, which were tainted too often with terms originating in nineteenth centre colonialism.

Her book Jamaica Anansi Stories (1924), republished in a revised edition by VAMzzz Publishing as Anansi, Jamaican stories of the Spider God, typifies her, in those days quite unique opinion on folklore. While many early folklorists believed that the term “folk” only referred to the oral culture of “savages”, Beckwith maintained that all cultures had folk traditions that warranted investigation. Many scholars also drew a firm line between “folk” and other “higher” forms of artistic expression. Beckwith believed both belonged in the literary tradition.

‘In 1920, Beckwith became the first person to hold a chair in Folklore at any college or university in the country.’

Beckwith graduated from Mount Holyoke College in 1893 and taught English at Elmira College, Mount Holyoke, Vassar College, and Smith College. In 1906, she obtained a Master of Arts degree in anthropology after studying under Franz Boas at Columbia University, and she received her Doctor of Philosophy in 1918. In 1920, Beckwith was appointed to the chair in Folklore at Vassar College.

During her sabbatical year of 1926-27, she studied folk literature in Italy, Greece, Palestine, Syria, and India. For the most part, however, she focused her study on Hawaii, Jamaica, and the Sioux and Mandan-Hidatsa Native American Reservations of North and South Dakota. There, she collected folklore from anyone willing to speak with her. The longest trips were to Hawaii, where she worked for the Bishop Museum while collecting local folk tales and songs. She became friendly with the people she met wherever she was. Her three summer trips to the Mandan-Hidatsa Native American Reservations made her close enough to the members of the Prairie Chicken Clan that they decided to initiate her. She became a full professor in 1929 and retired in 1938.

Other publications by Beckwith

- Folk-Games of Jamaica (with music recorded in the field by Helen H. Roberts). Poughkeepsie, N. Y.: Vassar College, 1922.

- Christmas Mummings in Jamaica. Poughkeepsie, N.Y.: Vassar College, 1923.

- Black Roadways: A Study of Jamaican Folk Life. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1929.

- Polynesian Analogues to the Celtic Other- World and Fairy Mistress Themes. New Haven, C.T.: Yale University Press, 1923.

- Jamaica Anansi Stories (with music recorded in the field by Helen Roberts). New York: American Folklore Society, 1924.

- Jamaica Proverbs. Poughkeepsie, N.Y.: Vassar College, 1925.

- Notes on Jamaican Ethnobotany. Poughkeepsie, N.Y.: Vassar College, 1927.

- Jamaica Folk-Lore. New York: American Folk-Lore Society. 1928.

- Myths and Hunting Stories of the Mandan and Hidatsa Sioux. Poughkeepsie, N.Y.: Vassar College, 1930.

- Mandan-Hidatsa Myths and Ceremonies. New York: American Folk-Lore Society, 1937.

- Hawaiian Mythology. New Haven, C.T.: Yale University Press, 1940.

- The Kumulipo: A Hawaiian Creation Chant. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1951.

Fire and Anansi

(Henry Spence, Bog, Westmoreland)

Anansi an’ Fire were good frien’. So Anansi come an’ see Fire an’ dey had dinner. So he invite Fire fe come see him now. So Fire tell him he kyan’t walk, So Fire tell him from him house him mus’ lay path dry bush, an’ him walk on top of dry bush. Anansi married to Ground Dove. Ground Dove tell him no, he mustn’t invite Fire; him wi’ bu’n him house an’ bu’n out himself. Anansi wouldn’t hear what him wife say, an’ he laid de trash on. An’ Fire bu’n from him house, an’ when he come near Anansi house he mak a big jump, bu’n Anansi, bu’n him house, bu’n eb’ryt’ing but him wife. Fire fool Anansi!

(Page 119, Anansi)

Anansi and Mr. Able

(Thomas White, Maroon Town)

Able have two daughter an’ dey was pretty young women. Anansi hear about dese two women, did want dem for wife, didn’t know what way he was to get dem. Able is a man couldn’t bear to hear no one call him name; for jus’ as he hear him name call, him get disturb all to kill himself. So Anansi get two ripe plantain an’ give de young women de two ripe plantain, an’ dey tek de two ripe plantain from Anansi an’ dey eat de two ripe plantain. Das de only way Anansi can get dese two young women.

An’ Able nebber know ‘bout it until one day Mr. Able deh at him house an’ him hear de voice of a singin’,—

“Brar Able o, me ruin’ o Me plant gone!”

Brar A-ble, oh, me ruin, oh, Brar A-ble,

oh, me ruin, oh, Brar A-ble, oh, me ruin, oh, Brar A-ble, oh, me plan-tain gone.

Brar Able say, “Well, from since I born I never know man speak my name in such way!” So he couldn’t stay in de house, an’ come out an’ went to plant sucker-root. Anansi go out,—

“Brar Able o, me ruin o, Me plant gone.”

Mr. Able went out from de sucker-root an’ he climb breadfruit tree. Anansi go just under de breadfruit tree, sing,

“Brar Able o, me ruin o, Me plant gone.”

Mr. Able went up in a cotton-tree, Anansi went up to de cotton-tree root, give out—

“Brar Able o, me ruin o, Me plant gone.”

An’ Mr. Able tek up himself off de cotton-tree an’ break him neck an’ Mr. Anansi tek charge Mr. Able house an’ two daughters.

Jack man dory, choose one!

(Page 250, Anansi)

Anansi seeks his Fortune

(Stanley Jones, Claremont, St. Ann)

Anansi was very poor and he went out to seek his fortune, but he had no intention of working. He clad himself in a white gown. And he met a woman. She said to him, “Who are you, sah? an’ whe’ you from?”—“I am jus’ from heaven.” The woman said, “Did you see my husban’ dere?” He said, “Well, my dear woman, heaven is a large place; you will have to tell me his name, for perhaps I never met him.” She said his name was James Thomas. Anansi said, “Oh, he is a good friend of mine! I know him well. He is a big boss up there and he’s carrying a gang. But one trouble, he has no Sunday clo’es.” The woman ran away and got what money she could together and gave it to Anansi to take to her husband.

But he wasn’t satisfied with that amount; he wanted some more. He went on a little further and saw a man giving a woman some money and telling her to put it up for ‘rainy day’. After the man had left, Anansi went up to the woman and told her he was “Mr. Rainy Day.” She said, “Well, it’s you, sah? My husband been putting up money for you for ten years now. He has quite a bag of it, and I’m so afraid of robbers I’m glad you come!” So Anansi took the money and returned home and lived contentedly for the rest of his days.

(Page 333, Anansi)

You may also like to read:

Pomba Gira or Pombajira and Exu

Mami Wata

Palo and Hoodoo

Umbanda, Brazilian Vodum and Santeria

VAMzzz Publishing book:

Anansi

Jamaican Stories of the Spider God

by Martha Warren Beckwith

English

ISBN 9789492355171

Paperback, book size 148 x 210 mm

494 pages