The witches of Benevento and their walnut tree Sabbath or Treguenda

As famous as Zugarramurdi, for its history of witchcraft in Spain, Benevento is best known as the Italian ‘Town of the Witches’. Even today this place breathes the magic of ancient times.

When the Romans conquered the area in the 3rd c. B.C. they changed its original name Maleventum (meaning “bad event”) into Beneventum (“good event”). Most important to them was that Benevento was a place of crossroads. The city stood where the Appian Way forked and the Sabato and Calore rivers came together. Crossroads were the special domain of the goddess Trivia, protector of witches (Tri-via meaning “three roads”).

The legend of the witches of Benevento dates back to the fourth century BC, when the ancient colonists of Magna Graecia introduced the orgiastic worship of Cybele.

For a brief period during Roman times, the cult of Isis, Egyptian goddess of the moon, proliferated in Benevento; also, the emperor Domitian had a temple erected in her honor. Within this cult Isis was part of a sort of Trimurti: she became identified with Hecate, goddess of the underworld, and Diana, goddess of the hunt. These deities were also connected with magic.

Notorious Renaissance witches

During the Renaissance, some of the most famous witches of Italy of that period lived and worked in, or in the region of Bernevento: Violante da Pontecorvo, Sorceress Menandra or Sorceress Alcina who, according to Pietro Piperno, author of the book ‘De nuce maga’, lived at about four miles distant from the town of Benevento, in the village of Pietra Pucina (little stone), which is now called Pietralcina. Other famous witches were Boiarona who, according to legend, had chained some demons to the walnut trees and the witch Gioconna. Gioconna was interrogated by the Holy Office of Rome in 1540 in the Arcistrega of Samnium. She was renowned for her beautiful apprentices, whom she taught how to rub their bodies with flying ointment.

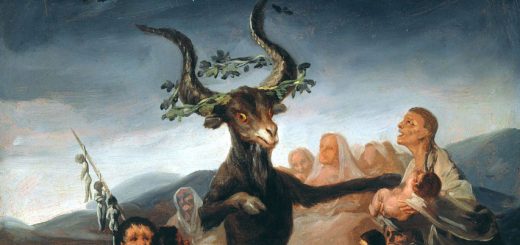

The Sabbath or Treguenda

…Unguent, unguent, Carry me to the walnut tree of Benevento, Above the water and above the wind, And above all other bad weather…’

The witches had the custom of nocturnal meetings, in the night between Saturday and Sunday, around a big walnut tree, to attend their Sabbath or Treguenda. People believed they traveled seated on flying broomsticks, after having anointed themselves with their witches unguent, which not only lifted them into the air but also made them invisible to the indiscreet eye.

The walnut tree of the witches of Benevento

Under the branches of a huge walnut tree a savage rite was performed. The locals really feared these women. They thought the witches could cause miscarriages and malformations in the newborns. They brushed against sleepers like a gust of wind and caused a sense of oppression on the chest, which at times was felt while they lay on their backs. Also feared were certain more “innocent” pranks, which, for example, would make the horses be found in their stables in the morning with their manes braided, or sweating from having been ridden all night. It was also believed they had the ability to enter their houses by moving their bodies under the doors during the nighttime. This could have been the source of their nickname Janara, which in dialect means ‘door’. Yet a more plausible theory links Janara to Dianare, priestesses of Diana. During the Roman era, the worship of Diana was widely spread in this region. The emperor Diocletian even built a temple in her honour.

The legend has it that the witches, indistinguishable from the other women by day, at night anointed their underarms or their breasts with an unguent and took off flying, pronouncing their magic phrase.

‘Nguento, ‘nguento,

mànname a lu nocio ‘e Beneviento,

sott’a ll’acqua e sotto ô viento,

sotto â ogne maletiempo.

Unguent, unguent,

Carry me to the walnut tree of Benevento,

Above the water and above the wind,

And above all other bad weather.

They were supposed to ride on brooms of sorghum. At the same time the witches became incorporeal, spirits like the wind; indeed, their preferred nights for flying were stormy ones.

The walnut tree of Benevento

The chief physician of Benevento, Pietro Piperno, in his essay On the Superstitious Walnut Tree of Benevento (1639, translated from his original Latin De Nuce Maga Beneventana), traced the roots of the witch legend back to the seventh century. At that time Benevento was the capital of a Lombard duchy. The invaders, although formally converted to Catholicism, did not renounce their traditional pagan religion. Under Duke Romuald I they worshiped a golden viper (perhaps winged, or with two heads), which probably had some connection with the cult of Isis, since the goddess was able to control serpents. They began to develop a singular rite near the Sabato river, which the Lombards celebrated in honor of Wotan, father of the gods: the hide of a goat was hung on a sacred tree. The warriors earned the favor of the god by rushing frantically around the tree on horseback and striking the hide with their lances, with the intent of tearing off shreds, which they then ate. In this ritual can be recognized the practice of diasparagmos, the god sacrificed and torn to pieces, which became the ritual meal of the devotees.

The Christians of Benevento would have connected these frenzied rites with their already-existing beliefs about witches: in their eyes the women and the warriors were witches, the goat was the incarnation of the Devil, and the cries were orgiastic rites.

A priest named Saint Barbatus of Benevento outright accused the Lombard rulers of idolatry. According to the legend, when Benevento was besieged by forces of the Byzantine emperor Constans II in 663, Duke Romuald promised Barbatus to renounce paganism if the city—and the duchy—were saved. Constans withdrew (according to the legend, by divine grace), and Romuald made Barbatus the bishop of Benevento.

Saint Barbatus cut down the sacred tree and tore out its roots, and on that spot he had a church built, called Santa Maria in Voto. Romuald continued to worship the golden viper in private, until his wife Teodorada handed it over to St. Barbatus, who melted it down to make a chalice for the Eucharist.

This legend is incompatible with the historical facts. In 663 the duke of Benevento was Grimoald, while Romuald I would not succeed his predecessor until 671, having become King of the Lombards in the meantime; moreover, Romualdo’s wife was named Theuderada—not Teodorada, who was instead the wife of Ansprand and mother of Liutprand. In any case, Paul the Deacon neither mentioned the legend, nor the presumed pagan faith of Romuald, who was much more likely to have been an Arian like his father Grimoald.

The meetings under the walnut tree, one of the main features of the witch legend, therefore very probably came from these Lombard customs; nevertheless, they are also found in the practices of the cultus of Artemis (the Greek goddess who can in part be assimilated to Isis), carried out in the Anatolian region of Caria.

For hundreds of years after it was uprooted, legend had it that the tree re-appeared on nights of the witch’s sabbats, the parties where supernatural folk gathered.

The location of the walnut tree

According to the testimony of the presumed witches, the walnut must have been a tall tree, ever green, and of a “noxious nature”. There are various hypotheses about the location of the Riverbank of the Janaras, the place on the bank of the Sabato where the walnut tree would be found. The legend does not rule out that there could have been more than one. Pietro Piperno, intending to prove the rumor to be false, included in his essay a map that indicated a possible positioning of several walnut tees.

Other versions have the walnut tree located in a gorge called the Strait of Barba, in Ceppaloni on the road to Avellino, where there was a grove flanked by an abandoned church, or in another location called Plain of the Chapels. Even the vanished Pagan Tower is spoken of, on which was built a chapel to St. Nicholas where the saint had worked numerous miracles. There were several nut trees forming a circular shape near what is now the Porta Rufina Station, just at the outskirts of the city, where witches would dance and chant: “To the nut tree of Benevento, over the water, over the wind.”

The witches of Benevento became a trade mark of their town, now known by the popular term “Town of the Witches”.

You may also like to read:

Witches ointment

Why did Witches Want to Ride their Broomsticks?

The incubus or succubus – nightmare or astral sex date?

Hecate – The Calling of the Crossroad Goddess

The Ancient Witch-Cult of The Basques

Walpurgis Night

Stefan Eggeler: Walpurgis Night witches, Kokain (Cocaine) and other illustrations

Witchcraft paintings – Dutch 17th century

Rosaleen Norton, Daughter of Pan

Mysteries of the Ancient Oaks

Black Cat Superstitions

The Mystical Mandrake

Little Secrets of the Poppy

Datura stramonium or jimson weed or zombi-cucumber

Mountain spirits

Wild Man or Woodwose

Sprite

sources:

http://www.witchesofbenevento.com/

http://insolitaitalia.databenc.it/

https://en.wikipedia.org/

VAMzzz Publishing book:

Etruscan Magic & Occult Remedies by Charles Godfrey Leland was first published as Etruscan Roman Remains in Popular Tradition, in 1892. Part One of the book offers a complete and detailed insight in the Etruscan and Roman rooted pantheon of the Tuscan Streghe (witches). Part Two describes many of their spells, incantations, sorcery and several lost divination methods.

Leland found himself at the crossroads of the academic and the romantic and it is precisely this, which makes the reading of his work so enjoyable. His primary aim was to preserve this ancient traditional knowledge, as he feared, it would soon be wiped out by modernism. Much information in this book, Leland received first hand from the Tuscan witches Maddalena and Marietta.

His second work on Stregheria: Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches was published seven years later in 1899. One could state he reached his goal, as his books are still of invaluable importance to both the Italian folklore and the modern practitioner of witchcraft. One of Leland’s readers was the late Gerald Gardner, which makes one wonder who was the true godfather of modern witchcraft… VAMzzz Publishing added an index of ancient Etruscan gods and spirits in this special revised edition.