The Domovoy and other Fairies of Russian folklore

In his Songs of the Russian People, W. R. S. Ralston gives us interesting information about the inferior inhabitants of their spirit-world, among them is the Domovoy (plural Domovuie). The belief in these beings was still very much alive in the 19th century. The Church has waged war against them for centuries, and has degraded and disfigured many of them, but although their expression has in many cases become greatly altered, according to Ralston, yet their original features may easily be recognized by a careful observer. The text below is the (extended) continuation of Ralston’s chapter: Demigods and Fairies.

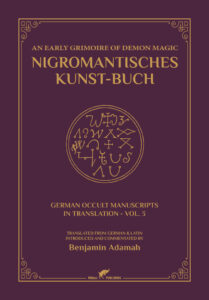

Drawing of the Domovoy, the Russian house spirit – by Ivan Bilibin, 1934

When Satan and all his hosts were expelled from heaven, says a popular legenda, some of the exiled spirits fell into the lowest recesses of the underground world, where they remain in the shape of Karliki or dwarfs. Some were received by the woods [lyesa], which they still haunt as Lyeshie, or sylvan demons, resembling fauns or satyrs; some dived into the waters [vodui], which they now inhabit under the name of Vodyanuie, or water-sprites; some remained in the air [vozdukh], and under the designation of Vozdushnuie delight in riding the whirlwind and directing the storm; and some have attached themselves to the houses [doma] of mankind, and have thence obtained the name of Domovuie, or domestic spirits. The distinctions made between the various groups of demons may be referred back to a very ancient period, but their demoniacal character, and the reason given for their appearance on earth, are the results of comparatively recent ideas about the world of spirits.

At least, a very great part of the opinions held by the peasants of modern Russia, with respect to these supernatural beings, are evidently founded upon the reverence paid by their forefathers to the spirits of the dead. From it, and from the ancient tendency to personify the elements, and pay divine honours to them, seem to have sprung most of the superstitions which to the present day make ghostly forms abound in woods and waters and about the domestic hearth. It is not necessary to dwell at any length in this chapter on the ideas and the customs of the Russian peasantry with respect to the dead, for they will be more fitly discussed in that devoted to “Funeral Songs,” but, in order to account for the characteristics of some of the inhabitants of the Slavonic fairy-land, it will be as well to say something about the views which the old Slavonians held with reference to the unseen world. It is especially to the Domovoy or house-spirit, and the Rusalka, a species of Naiad or Undine, that they apply.

Funeral customs and the journey of the dead

The Slavonians believed that after death the soul had to begin a long journey. According to one idea it was obliged to sail across a wide sea, and therefore coins intended for the spirit’s passage-money were placed in every grave. This practice is still kept up among the Russian peasants, who throw small copper or silver coins into the grave at a funeral, though in many cases they have lost sight of the original meaning of the custom. To the idea of this voyage, also, some of the archæologists are inclined to turn for an explanation of the old Slavonic custom of burning or burying the dead in boats, or boat-shaped coffins.

Silesian Domovoy statue

According to another idea the journey had to be made on foot, and so a corpse was sometimes provided with a pair of boots, intended to be worn during the pilgrimage and discarded at its termination, a custom said to linger still among the Bohemian peasants. Kotlyarevsky thinks that there is reason to suppose that a conductor of the dead was known to the old Slavonians, and as their Psychopomp he is inclined to recognize the deity whom Dlugosz mentions under the name of Nija, and compares with Pluto, but whom another old writer calls “The Leader.” And Afanasief thinks that some connexion may be traced between the dark dogs of Yama, which guarded the road to the dwelling-place of the Fathers, and the black dog which in Ruthenia, when a dying man’s agony is greatly prolonged, is passed through a hole made in the roof over his head, in the hope of thereby expediting the liberation of the soul from the body. But these are mere conjectures. What is certain is that the Slavonians believed in a road leading from this to the other world, sometimes recognizing it in the rainbow, but more often in the Milky Way. To the latter various names, associated with this old belief, are still given by the Russian peasants. In the Nijegorod Government it is called the “Mouse Path,” the mouse being a well-known figure for the soul. In that of Tula it is the Stanovishche, the “Traveller’s Halting-Place.”

About Perm it is known as the “Road to Jerusalem;” the Tambof peasantry call it “Baty’s Road,” and say that it runs from the “Iron Hills,” within which are confined the Tartar invaders whom Baty used to lead–the original idea having been, in all probability, that the path led from the cloud-hills in which the spirits of the storm were imprisoned, for in the middle ages the Tartars were commonly substituted in legends for the evil spirits of an earlier age. In the Government of Yaroslaf the Raskolniks say that there is a sacred city hidden beneath deep waters, in which the “Holy Elders” live, and that Baty’s Road led thither. The Holy Elders are the dead, whom the Russian peasant still addresses as Roditeli, a term exactly answering to the Vedic Pitris, or Fathers. At the head of the Milky Way, according to a Tula tradition, there stand four mowers, who guard the sacred road, and cut to pieces all who attempt to traverse it–a myth closely akin to that of Heimdall, the Scandinavian watcher of the Rainbow-bridge between heaven and earth.

A third view of the soul’s wanderings was that it had to climb a steep hill-side, sometimes supposed to be made of iron, sometimes of glass, on the summit of which was situated the heavenly Paradise. And, therefore, if the nails of a corpse were pared, the parings were placed along with it in the grave, a custom still kept up among the Russian peasantry. The Raskolniks, indeed–the Russian Nonconformists, among whom old ideas are religiously kept alive–are in the habit of carrying about with them, in rings or amulets, parings of an owl’s claws and of their own nails. Such relies are supposed by the peasantry in many parts of Russia to be of the greatest use to a man after his death, for by their means his soul will be able to clamber up the steep sides of the hill leading to heaven. The Lithuanians, it is well known, held similar ideas, and used to burn the claws of wild beasts on their funeral pyres.

https://vamzzz.com/product/spirit-beings-in-european-folklore-3/

Before ascending the high hill or crossing the wide sea, the soul had to rise from the grave, and therefore certain aids to climbing were buried with the corpse. Among these were plaited thongs of leather and small ladders. One of the most interesting specimens of Survival to be found among the customs of the Russian peasantry is connected with this idea. Even at the present day, when many of them have forgotten the origin of the custom, they still, in some districts, make little ladders of dough, and have them baked for the benefit of the dead. In the Government of Voroneje a ladder of this sort, about three feet high, is set up at the time when a coffin is being carried to the grave; in some other places similar pieces of dough are baked in behalf of departed relatives on the fortieth day after their death, or long pies marked crossways with bars are taken to church on Ascension Day and divided between the priest and the poor.

In some villages these pies, which are known as Lyesenki, or “Ladderlings,” have seven bars or rungs, in reference to the “Seven Heavens.” The peasants fling them down from the belfry, and accept their condition after their fall as an omen of their own probable fate after death. A Mazovian legend tells how a certain pilgrim, on his way to worship at the Holy Sepulchre, became lost in a rocky place from which he could not for a long time extricate himself. At last he saw hanging in the air a ladder made of birds’ feathers. Up this he clambered for three months, at the end of which he reached the Garden of Paradise, and entered among groves of gold and silver and gem-bearing trees, all of which were familiar with the past, the present, and the future.

Silesian Domovoy statue

The abode of the dead was known to the old Slavonians under three names, Rai, Nava, and Peklo. They originally, it is supposed, had the same meaning, but in the course of time the first and the last became associated with two different sets of ideas, and in modern Russian Rai stands for Heaven and Peklo for Hell. The word Rai, in Lithuanian rojus, is derived by Kotlyarevsky from the Sanskrit root raj, and one of its forms, Vuirei, is compared by Afanasief with the Elysian vireta of Virgil. According to many Slavonic traditions, this Rai, Iry, or Vuirei is the home of the sun, lying eastward beyond the ocean, or in an island surrounded by the sea. Thither repairs the sun when his day’s toil is finished; thither also fly the souls of little children [provided that they have not died unchristened], and there they play among the trees and gather their golden fruits. There, according to a tradition current among the Lithuanians, as well as among some of the Slavonic peoples, dwell the spirits which at some future time are to be sent to live upon earth in mortal bodies, and thither, when disembodied, will they return. No cold winds ever blow there, winter never enters those blissful realms, in which are preserved the seeds and types of all things that Eve upon the earth, and whither birds and insects repair at the end of the autumn, to re-appear among men with the return of spring.

There seems to have prevailed in almost all parts of the world a belief in the existence of Happy Islands lying towards the west, the home of the setting sun, but among the Slavonians there appears to have been widely spread some idea,–due probably to the apocryphal books about Alexander of Macedon,–of eastern climes to which they attached the idea of perennial warmth and light. Thus, in Galicia, there still lingers a tradition that somewhere far away, beyond the dark seas, and in the land from which the sun goes forth to run his daily course, there dwells the happy nation of the Rakhmane. They lead a holy life, for they abstain from eating flesh all the year round, with the exception of one day, “the Rakhmanian Easter Sunday.” And that festival is celebrated by them on the day on which the shell of a consecrated Easter egg floats to them across the wide sea which divides them from the lands inhabited by ordinary mortals. The name of these Easterns, who seem akin to Homer’s “blameless Ethiopians” explains itself. The people who were Brahmans have become Rakhmane, and their name has gradually passed, in the minds of the people, into an expression for persons who are (1) joyous, hospitable, etc., (2) soft, mild, etc., (3) dreary, weak-minded, etc.

The derivation of the second term for the home of the dead, Nava, is uncertain. The word nav, nav’e, means a mortal, and unaviti is to kill. Comparisons have been made by the philologists between nava and the Sanskrit and Greek naus, or the Latin navis, as well as with nekus, but all that can be deduced from such comparisons is that in nava there may possibly be some reference to the sea traversed by the dead, the atmospheric ocean across which the winds breathe. The primary meaning of the third designation, Peklo, seems to be that of a place of warmth, being derived from the same root as Pech’, [as a verb] to parch, [as a substantive] a stove, etc. After a time it probably acquired the’ signification of the abode of bad souls only, and under the influence of Christian teaching it became Hell, the subterranean place of punishment in which evil spirits torment the souls of the wicked.

Side by side with the traditions which point to a distant habitation of the dead, there exist others in which the grave itself is spoken of as the home of the departed spirit. “Dark and joyless is our prison-house,” is the reply constantly made by ghosts when questioned as to their habitation. “Stone and earth lie heavy on our hearts, our eyes are fast closed, our hands and feet are frozen by the cold.” Especially during the winters do the dead suffer; when the spring returns the peasants say, “Our fathers enjoy repose,” and in Little-Russia they add, “God grant that the earth may lie light on you, and that your eyes may see Christ!” It is this idea of residence in the material grave that lies at the root of the custom of periodically visiting and pouring libations on the tombs of departed relatives, with which we shall meet in the section devoted to funeral songs.

The old heathen Slavonians seem to have had no idea of a future state in which present wrongs should be redressed, or griefs assuaged. They appear to have looked on the life beyond the grave as a mere prolongation of that led on earth–the rich man retained at least some of his possessions; the slave remained a slave. Thus wedded people were supposed to live together in a future state, an opinion on which some of the funeral ceremonies of the present day are founded, and which, in heathen times, frequently induced wives to kill themselves when their husbands died. The Bulgarians hold the same doctrine even at the present day, and therefore among them widows seldom marry. Nor does a widower often find any one but a widow who will accept, him, for in the world to come, it is supposed, his first wife will claim him and take him away from her successor.

The soul after death belief among the slavonic people

After death the soul at first remains in the neighbourhood of the body, and then follows it to the tomb. The Bulgarians hold that it assumes the form of a bird or a butterfly, and sits on the nearest tree waiting till the funeral is over. Afterwards it sets out on its long journey, accompanied by an attendant angel. The Mazovians say that the soul remains with the coffin, sitting upon the upper part of it until the burial is over, when it flies away. Such traditions as these vary in different localities, but every where, among all the Slavonic people, there seems always to have prevailed an idea that death does not finally sever the ties between the living and the dead. This idea has taken various forms, and settled into several widely differing superstitions, lurking, for instance, in the secrecy of the cottage, and there keeping alive the cultus of the domestic spirit, or showing itself openly in the village church, where on a certain day it calls for a service in remembrance of the dead. The spirits of those who are thus remembered, say the peasants, attend the service, taking their place behind the altar. But those who are left unremembered weep bitterly all through the day.

Šetek or Skřítek, the Bohemian version of Domovoy in his Christianised representation as a hellish hobgoblin

In the mythic songs and stories current among the old Slavonians the soul of man was represented under various forms, by numerous images. Ancient traditions affirmed that it was a spark of heavenly fire, kindled in the human body by the thunder-god. And in accordance with this idea the superstition of the Russian peasant of to-day often sees ghostly flames gleaming above graves, not to be banished till the necessary prayers have been said–still believes that of a wedded couple that one will die the first whose taper was first extinguished at the time of the marriage ceremony. In the Government of Perm the peasants hold that there are just as many stars in the sky as there are human beings on earth, a new star appearing whenever a babe is born, and disappearing when its corresponding mortal dies. In Ruthenia a shooting star is looked upon as the track of an angel flying to receive a departed spirit, or of a righteous soul going up to heaven. In the latter case, it is believed that if a wish is uttered at the moment when the star shoots by, it will go straight up with the rejoicing spirit to the throne of God. So, when a star falls, the Servians say “Some one’s light has gone out,” meaning some one is dead.

Besides being likened to fire and a star, the soul is often represented by Russian tradition as a smoke, or vapour, or a current of air. In the Stikhi, or popular religious poems, the Angel of Death receives the disembodied spirit from “the sweet lips” of the righteous dead, an idea which prevails also among the people of South Siberia, who hold that a man’s soul has its residence in his windpipe. A shadow, also, is as common a metaphor for the soul in Russia as elsewhere, whence it arises that, even at the present day, there are persons there who object to having their silhouettes taken, fearing that if they do so they will die before the year is out. In the same way, a man’s reflected image is supposed to be in communion with his inner self, and therefore children are often forbidden to look at themselves in a glass, last their sleep should be disturbed at night. In the opinion of the Raskolniks a mirror is an accursed thing, invented by the devil.

The butterfly seems to have been universally accepted by the Slavonians as an emblem of the soul. In the Government of Yaroslav, one of its names is dushichka, a caressing diminutive of dusha, the soul. In that of Kherson it is believed that if the usual alms are not distributed at a funeral, the dead man’s soul will reveal itself to his relatives in the form of a moth flying about the flame of a candle. The day after receiving such a warning visit, they call together the poor, and distribute food among them. In Bohemia tradition says that if the first butterfly a man sees in the spring is a white one, he is destined to die within the year. The Servians believe that the soul of a witch often leaves her body while she is asleep, and flies abroad in the shape of a butterfly. If during its absence her body be turned round, so that her feet are placed where her head was before, the soul-butterfly will not be able to find her mouth, and so will be shut out from her body. Thereupon the witch will die. Gnats and flies are often looked upon as equally spiritual creatures. In Little-Russia the old women of a family will often, after returning from a funeral, sit up all night watching a dish in which water with honey in it has been placed, in the belief that the spirit of their dead relative will come in the form of a fly, and sip the proffered liquid.

https://vamzzz.com/product/the-meaning-of-the-360-zodiacal-degrees/

A common belief among the Russian peasantry is that the spirits of the departed haunt their old homes for the space of six weeks, during which they eat and drink, and watch the sorrowing of the mourners. After that time they fly away to the other world. In certain districts bread-crumbs are placed on a piece of white linen at a window during those six weeks, and the soul is believed to come and feed upon them in the shape of a bird. It is generally into pigeons or crows that the dead are transformed. Thus when the Deacon Theodore and his three schismatic brethren were burnt in 1681, the souls of the martyrs, as the “Old-Believers” affirm, appeared in the air as pigeons. In Volhynia dead children are supposed to come back in the spring to their native village under the semblance of swallows and other small birds, and to seek by soft twittering or song to console their sorrowing parents. The cuckoo, also, according to Slavonic superstitions, is intimately connected with the dead. In Little-Russia she flies to weep over corpses. The Servians and Lithuanians look on her as a sister whom nothing can console for the loss of a brother; and in a Russian marriage-song the orphan bride implores the cuckoo to fetch her dead parents from the other world, that they may bless her before she enters on her new life.

The Domovoy and the ancestors

Kikimora – Aleksandr Golovin’s sketch for a costume for Stravinsky’s The Firebird. The Kikimora is sometimes seen as the female version of the Domovoy.

It is evident, from what has been said, that the views of the Old Slavonians about a future state were not defined with any great precision, and it is not easy to decide what were the exact opinions they held as to the relations between the inhabitants of this world and of the other. But there can be no doubt about their belief that the souls of fathers watched over their children and their children’s children, and that therefore departed spirits, and especially those of ancestors, ought always to be regarded with pious veneration, and sometimes solaced or conciliated by prayer and sacrifice. It is clear, moreover, that the cultus of the dead was among them, as among so many other peoples, closely connected with that of the fire burning on the domestic hearth, a fact which accounts for the stove of modern Russia having come to be considered the special haunt of the Domovoy, or house-spirit, whose position in the esteem of the people is looked upon as a trace of the ancestor worship of olden days. He is, of course, merely the Slavonic counterpart of the house-spirit of other lands, but his memory has been so well preserved in Russia, and so many legends are current about him, that he seems well worthy of a detailed notice.

Since the introduction of Christianity into Russia, something of a demoniacal nature has attached itself to the character and the appearance of the Domovoy, which may account for the fact that he is supposed to be a hirsute creature, the whole of his body, even to the palms of his hands and the soles of his feet, being covered with thick hair. Only the space around his eyes and nose is bare. The tracks of his shaggy feet may be seen in winter time in the snow; his hairy hands are felt by night gliding over the faces of sleepers. When his hand feels soft and warm it is a sign of good luck: when it is cold and bristly, misfortune is to be looked for.

He is supposed to live behind the stove now, but in early times he, or the spirits of the dead ancestors, of whom he is now the chief representative, were held to be in even more direct relations with the fire on the hearth. In the Nijegorod Government it is still forbidden to break up the smouldering remains of the faggots in a stove with a poker; to do so might be to cause one’s “ancestors” to fall through into Hell. The term “ancestors” is universally applied to the defunct, even when dead children are being spoken of. When a Russian family moves from one house to another, the fire is raked out of the old stove into a jar and solemnly conveyed to the new one, the words “Welcome, grandfather, to the new home!” being uttered when it arrives. This and the following custom have been supposed to point to a time when the spirit and the flame were identified, and when some now forgotten form of fire-worship was practised:–On the 28th of January the peasants, after supper, leave out a pot of stewed grain for the Domovoy. This pot is placed on the hearth in front of the stove, and surrounded with hot embers. In olden days, says Afanasief, the offering of corn was doubtless placed directly on the fire.

In some districts tradition expressly refers to the spirits of the dead the functions which are generally attributed to the Domovoy, and they are supposed to keep careful watch over the house of a descendant who honours them and provides them with due offerings. Similarly among the (non-Slavonic) Mordvins in the Penza and Saratof Governments, a dead man’s relations offer the corpse eggs, butter, and money. saying: “Here is something for you: Marfa has brought you this. Watch over her corn and cattle, and when I gather the harvest, do thou feed the chickens and look after the house.”

In Galicia the people believe that their hearths are haunted by the souls of the dead, who make themselves useful to the family, and there are many Czekhs who still hold that their departed ancestors look after their fields and herds, and assist in hunting and fishing. Directly after a man’s burial, according to them, his spirit takes to wandering by nights about the old home, and watching that no evil befalls his heirs.

https://vamzzz.com/product/giants-and-dwarfs/

Domestic spirits and the importance of the stove

In Lithuania the name given to the domestic spirits is Kaukas, a term which has never been thoroughly explained. They are little creatures, like the German kobolds, being not more than a foot high. The peasants sometimes make tiny cloaks, and bury them in the ground within the cottage; the Kaukas put them on, and thenceforward devote their energies to serving the friendly proprietor of the house. But if they are badly used or neglected, they set his homestead on fire. Similar little beings, called Krosnyata, or dwarfs, are supposed to exist among the Kashoubes, the Slavonic inhabitants of a part of the coast of the Baltic. The Ruthenians reverence in the person of the Domovoy the original constructor of the family hearth. He has a wife and daughters, who are beautiful as were the Hellenic Nymphs, but their favours are deadly to mortal men. In one district of the Viatka Government the Domovoy is described as a little old man, the size of a five-year-old boy. He wears a red shirt with a blue girdle; his face is wrinkled, his hair is of a yellowish grey, his beard is white, his eyes glow like fire. In other places his appearance is much the same, only sometimes he wears a blue caftan with a rose-coloured girdle. Every where he is given to grumbling and quarrelling, and always expresses himself in strong, idiomatic phrases. In Lusatia he takes the form of a beautiful boy, who goes about the house dressed in white, and warns its inhabitants, by his sad groaning, of impending woe. When hot water is going to be poured away, it is customary there to give warning to the Domovoy, that he may not be scalded.

The Russian Domovoy hides behind the stove all day, but at night, when all the house is asleep, he comes forth from his retreat, and devours what is, left out for him. In some families a portion of the supper is always set aside for him, for if he is neglected he waxes wroth, and knocks the tables and benches about at night. Wherever fires, are lighted, there the Domovoy is to be found, in baths, in places for drying corn, and in distilleries. When he haunts a bath (banya) he is known as a Bannik; the peasants avoid visiting a bath at late hours, for the Bannik does not like people who bathe at night, and often suffocates them, especially if they have not prefaced their ablutions by a prayer. It is considered dangerous, also, to pass the night in a corn-kiln, for the Domovoy may strangle the intruder in his sleep. In the Smolensk Government it is usual for peasants who quit a bath to leave a bucket of water and a whisk for the use of the Domovoy who takes, their place. In Poland it is believed that the Domovoy is so loath to quit a building in which he has once taken up his quarters, that even if it is burnt down he still haunts it, continuing to dwell in the remains of the stove. And so they say there, “In an old stove the devil warms,” for the devil and the Domovoy are often synonymous terms in the mouths of the people, who regard Satan with more sorrow than anger. In Galicia the, following story is told “About the Devil in the Stove:”–

There was a hut in which no one would live, for the children of every one who had inhabited it had died, and so it remained empty. But at last there came a man who was very poor, and he entered the hut, and said, “Good day to whomsoever is in this house!” “What dost thou want?” cried out the Old One 1. “I am poor; I have neither roof nor courtyard,” sadly said the new comer. “Live here,” said the Old One, “only tell thy wife to grease the stove every week, and look after thy children that they mayn’t lie down upon it.” So the poor man settled in that hut, and lived in it peacefully with all his family. And one evening, when he had been complaining about his poverty, the Old One took a whole potful of money out of the stove and gave it him.

In Galicia and Poland a belief is current in the existence of an invisible servant who lives in the stove, is called Iskrzycki [Iskra is Polish for a spark], and most zealously performs all sorts of domestic duties for the master of the house. In White-Russia the Domovoy is called Tsmok, a snake, one of the forms under which the lightning was most commonly personified. This House Snake brings all sorts of good to the master who treats it well and gives it omelettes, which should be placed on the roof of the house or on the threshing-floor. But if this be not done the snake will burn down the house. It rarely shows itself to mortal eyes, and when it does so, it is generally to warn the heads of the family to which it is attached of some coming woe.

“Once upon a time a servant maid awoke one morning, lighted the fire, and went for her buckets to fetch water. Not a bucket was to be seen! Of course she thought ‘a neighbour has taken them.’ Out she ran to the river, and there she saw the Domovoy–a little old man in a red shirt–who was drawing water in her buckets, to give the bay mare to drink, and he glared ever so at the girl–his eyes burned just like live coals! She was terribly frightened, and ran back again. But at home there was woe! All the house was in a blaze!”

Domovoy as guardian of herds and stables

It is said that the Domovoy does not like to pass the night in the dark, so he often strikes a light with a flint and steel, and goes about, candle in hand, inspecting the stables and outhouses. Hence he derives a number of his names. Sometimes he appears as Vazila [from vozit’, to drive], the protector of horses, a being in shape like a man, but having equine ears and hoofs; at other times as Bagan, he is guardian of the herds, taking up his quarters in a little crib filled for his benefit with hay. On Easter Sunday and the preceding Thursday he becomes visible, and may be seen crouching in a corner of his stall. He is very fond of horses, and often rides them all night, so that they are found in the morning foaming and exhausted. Sometimes, also, he goes riding on a goat. When a newly purchased animal is brought home for the first time, it is customary in several places to go through the following ceremony. The animal is led to its stall, and then its possessor bows low, turning to each of the four corners of the building in succession, and says, “Here is a shaggy beast for thee, Master! Love him, give him to eat and to drink!” And then the cord by which the animal was led is attached to the kitchen-stove.

Animal sacrifice for a new house

With the idea that each house ought to have its familiar spirit, and that it is the soul of the founder of the homestead which appears in that capacity, may be connected the various superstitious ideas which attach themselves in Slavonic countries to the building of a new house. The Russian peasant believes that such an act is apt to be followed by the death of the head of the family for which the new dwelling is constructed, or that the member of the family who is the first to enter it will soon die. In accordance with a custom of great antiquity, the oldest member of a migrating household enters the new house first, and in many places, as for instance, in the Government of Archangel, some animal is killed and buried on the spot on which the first log or stone is laid. In other places the carpenters who are going to build the house call out, at the first few strokes of the axe, the name of some bird or beast, believing that the creature thus named will rapidly consume away and perish. On such occasions the peasants take care to be very civil to the carpenters, being assured that their own names might be pronounced by those workmen if they were neglected or provoked. The Bulgarians, it is said, under similar circumstances, take a thread and measure the shadow of some casual passer-by. The measure is then buried under the foundation-stone, and it is expected that the man whose shadow has been thus treated will soon become but a shade himself. If they cannot succeed in getting at a human shadow, they make use of the shadow of the first animal that comes their way.

Sometimes a victim is put to death on the occasion, the foundations of the house being sprinkled with the blood of a fowl, or a lamb, or some other species of scapegoat, a custom which is evidently derived from that older one of offering sacrifices in honour of the Earth Goddess, when a new house was being founded. In Servia a similar idea used to apply to the fortifications of towns. No city was thought to be secure unless a human being, or at least the shadow of one, was built into its walls. When a shadow was thus immured, its owner was sure to die quickly. There is a well-known Servian ballad–one of those translated by Sir John Bowring–in which is described the building of Skadra [the Bulgarian Scutari] by a king and his two brothers. At first they cannot succeed in their task, for the Vilas pull down at night what has been built in the day, so they determine to build into the wall whichever of the three princesses, their wives, comes out the first to bring them refreshment. The two elder brothers warn their wives, who pretend to be ill, but the youngest of the ladies hears nothing about the agreement, so, she comes out, and is at once seized upon by her brothers-in-law, and immured alive.

A similar story is told about the second founding of Slavensk. The city was built by a colony of Slaves from the Danube. A plague devastated it, so they determined to give it a new name. Acting on the advice of their wisest men, they sent out messengers before sunrise one morning in all directions, with orders to seize upon the first living creature they should meet. The victim proved to be a child (Dyetina, archaic form of Ditya), who was buried alive under the foundation-stone of the new citadel. The city was on that account called Dyetinets, a name since applied to any citadel. The city was afterwards laid waste a second time, on which its inhabitants removed to a short distance, and founded a new city, the present Novgorod.

Domovoy as Banshee

The Domovoy often appears in the likeness of the proprietor of the house, and sometimes wears his clothes. For he is, indeed, the representative of the housekeeping ideal as it presents itself to the Slavonian mind. He is industrious and frugal, he watches over the homestead and all that belongs to it. When a goose is sacrificed to the water-spirit, its head is cut off and hung up in the poultry-yard, in order that the Domovoy may not know, when he counts the heads, that one of the flock has gone. For he is jealous of other spirits. He will not allow the forest-spirit to play pranks in the garden, nor witches to injure the cows. He sympathizes with the joys and sorrows of the house to which he is attached. When any member of the family dies, he may be heard (like the Banshee) wailing at night; when the head of the family is about to die, the Domovoy forebodes the sad event by sighing, weeping, or sitting at his work with his cap pulled over his eyes. Before an outbreak of war, fire, or pestilence, the Domovoys go out from a village and may be heard lamenting in the meadows. When any misfortune is impending over a family, the Domovoy gives warning of it by knocking, by riding at night on the horses till they are completely exhausted, and by making the watch-dogs dig holes in the courtyard and go howling through the village. And he often rouses the head of the family from his sleep at night when the house is threatened with fire or robbery.

https://vamzzz.com/product/the-great-sea-serpent/

Quarreling and unfriendly Domovuie

The Russian peasant draws a clear line between his own Domovoy and his neighbour’s. The former is a benignant spirit, who will do him good, even at the expense of others; the latter is a malevolent being, who will very likely steal his hay, drive away his poultry, and so forth, for his neighbour’s benefit. Therefore incantations are provided against him, in some of which the assistance of “the bright gods” is invoked against “the terrible devil and the stranger Domovoy.” The domestic spirits of different households often engage in contests with one another, as might be expected, seeing that they are addicted to stealing from each other’s possessions. Sometimes one will vanquish another, drive him out of the house he haunts, and take possession of it himself. When a peasant moves into a new house, in certain districts, he takes his own Domovoy with him, having first, as a measure of precaution, taken care to hang up a bear’s head in the stable. This prevents any evil Domovoy, whom malicious neighbours may have introduced, from fighting with, and perhaps overcoming, the good Lar Familiaris.

English Robin Goodfellow illustration dated 1639.

Each Domovoy has his own favourite colour, and it is important for the family to try and get all their cattle, poultry, dogs and cats of this hue. In order to find out what it is, the Orel peasants take a piece of cake on Easter Sunday, wrap it in a rag, and hang it up in the stable. At the end of six weeks they look at it to see of what colour the maggots are which are in it. That is the colour which the Domovoy likes. In the Governments of Yaroslaf and Nijegorod the Domovoy takes a fancy to those horses and cows only which are of the colour of his own hide. There was a peasant once, the story runs, who lost all his horses because they were of the wrong colour. At last the poor man, who was almost ruined, bought a miserable hack, which was of the right hue. “What a horse! there’s something like a horse! Quite different from the other ones!” exclaimed the delighted Domovoy, and from that moment all went well with the peasant. It is a terrible thing for a family when a strange Domovoy gets into a house and turns out its friendly spiritual occupant. The new comer plays all the pranks attributed to

“That shrewd and knavish sprite,

Call’d Robin Goodfellow,”

pinches sleepers as the fairies in Windsor Park pinched Falstaff, but without equally good reason, and renders life a burden to the haunted household. Fortunately there is a means of expelling him, which is to take brooms, and with them to strike the walls and fences, exclaiming, “Stranger Domovoy, go away home!” and on the evening of the same day to dress in holiday array, and go out into the yard, and call out to the original tenant of the hearth, “Grandfather Domovoy! Come home to us–to make habitable the house and tend the cattle!” Another means is to ride on horseback about the yard, waving a fire-shovel in the air, and uttering an incantation. Sometimes the shovel is dipped in tar. When the Domovoy rubs his head against it he is disgusted, and quits the house.

Sometimes a man’s own Domovoy takes to behaving unpleasantly to him, for the domestic spirits have a dual nature, answering to that which the old Slavonians attributed to the spirits of the storm. The same forces of nature which fattened the earth and made it bring forth harvests, often manifested themselves as destructive agents; so the Domovoy, although generally good to his friends, sometimes does them harm, just as fire is at one time friendly to man, at another hostile. Every now and then, the peasants believe, a house becomes haunted by teazing, if not absolutely malicious beings, who make terrible noises at night, throw about sticks and stones, and in various ways annoy the sleeping members of the family. When the regular Domovoy does this, all he needs in general is a mild scolding. Various stories prove the truth of this assertion. Here is one of them. In a certain house the Domovoy took to playing pranks. “One day, when he had caught up the cat, and flung her on the ground, the housewife expostulated with him as follows: ‘Why did you do that? Is that the way to manage a house? We can’t get on without our cat. A pretty manager, forsooth!’ And from that time the Domovoy gave up troubling the cats.”

Domovoy as incubus

Kikimora by by Ivan Bilibin, 1934

One of the many points in which the Domovoy resembles the Elves with whom we are so well acquainted, is his fondness for plaiting the manes of horses. Another is his tendency to interfere with the breathing of people who are asleep. Besides plaiting manes, he sometimes operates in a similar manner upon men’s beards and the back hair of women, his handiwork being generally considered a proof of his goodwill. But when he plays the part of our own nightmare, he can scarcely be looked upon as benignant. The Russian word for such an incubus is Kikimora or Shiskimora (the French Cauche-mare). The first half of the word, says Afanasief, is probably the same as the provincial expression shish = Domovoy, demon, etc. The second half means the same as the German mar or our mare in nightmare. In Servia, Montenegro, Bohemia, and Poland the word answering to mora, means the demoniacal spirit which passes from a witch’s lips in the form of a butterfly, and oppresses the breathing of sleepers at night. The Russians believe in certain little old female beings called Marui or Marukhi, who sit oil stoves and spin by night. No woman in the Olonets Government thinks of laying aside her spindle without uttering a prayer. If she forgot to do so the Mara would come at night and spoil all her work for her. The Kikimori are generally understood to be the souls of girls who have died unchristened, or who have been cursed by their parents, and so have passed under the power of evil spirits. According to a Servian tradition the Mora sometimes turns herself into a horse, or into a dlaka, or tuft of hair. Once a Mora so tormented a man that he left his home, took his white horse and rode away on it. But wherever he wandered the Mora followed after him. At last he stopped to pass the night in a certain house, the master of which heard him groaning terribly in his sleep, so he went to look at him. Then he saw that his guest was being suffocated by a long tuft of white hair which lay over his mouth. So he cut it in two with a pair of scissors. Next morning the white horse was found dead. The horse, the tuft of hair, and the nightmare, were all one.

https://vamzzz.com/product/the-book-of-halloween/

On the 30th of March the Domovoy turs malicious

The Domovoy generally turns malicious on the 30th of March, and remains so from early dawn till midnight. At that time he makes no distinction between friends and strangers, so it is as well to keep the cattle and poultry at home that day, and not to go to the window more than is necessary. It is uncertain whether his short-lived fury at that season of the year arises from the fact that he is then changing his coat. Some authorities hold that a kind of mania comes over him then, others that he feels a sudden craving to get married to a witch. Anyhow it is considered wise to propitiate him by offerings. These gifts can take almost any edible shape. In the Tomsk Government, on the Eve of the Epiphany, the peasants place in a certain part of the stove little cakes made expressly for the Domovoy. In other places a pot of stewed grain is set out for him on the evening of the 28th of January. Exactly at midnight he comes out from under the stove, and sups off it. If he is neglected he waxes wroth, but he may be appeased as follows:–A wizard is called in, who kills a cock and lets its blood run on to one of the whisks used in baths; with this in hand he sprinkles the corners of the cottage inside and out, uttering incantations the while. It may be as well to remark, that while unclean spirits fear the crowing of cocks, it never in any way affects the Domovoy.

Another way of pacifying the irritated domestic spirit is for the head of the family to go out at midnight into the courtyard, to turn his face to the moon, and to say, “Master! stand before me as the leaf before the grass [an ordinary formula], neither black nor green, but just like me! I have brought thee a red egg.” Thereupon the Domovoy will assume a human form, and, when he has received the red egg, will become quiet. But the peasant must not talk about this midnight meeting. If he does, the Domovoy will set his cottage on fire, or will induce him to commit suicide.

The threshold opposite the stove

We have already mentioned the custom of literally or figuratively sacrificing a victim on the spot which a projected house is to cover. Generally speaking that victim is a cock, the head of which is cut off and buried, in all privacy, exactly where the “upper corner” of the building is to stand. This corner, opposite to which stands the stove, is looked upon with great reverence by the peasants, who call it also the “Great” and the “Beautiful.” There the table stands on which is spread the daily meal in which the ancestors of the family were always supposed to participate. In all probability, says one Russian commentator, their images used to stand close by, and were transferred to the table at meal-time, but since the introduction of Christianity they have been replaced by holy icons, or sacred pictures. In that same corner every thing that is most revered is placed, as Paschal eggs and Whitsuntide verdure. Towards it every one who enters the cottage makes low obeisance. The peasants still believe that the souls of the dead, as soon as the bodies they used to inhabit are buried, take up their quarters in the cottage behind the sacred pictures, and therefore they place hot cakes upon the ledge which supports those pictures, intending them as an offering to the hungry ghosts. The sound of the death-watch is believed to be as ominous in Russia as in England, In Bohemia it is supposed to be caused by such ghosts as have just been mentioned, who are knocking in order to summon one of their descendants to join them.

The threshold of a cottage is not so important as its “front corner,” but many curious superstitions are attached to it. On it a cross is drawn to keep off Maras (hags). Under it the peasants bury stillborn children. In Lithuania, when a new house is being built, a wooden cross, or some article which has been handed down from past generations, is placed under the threshold. There, also, when a newly-baptized child is being brought back from church, it is customary for its father to hold it for a while over the threshold, “so as to place the new member of the family under the protection of the domestic divinities.” On the other side of the threshold that power which produces peace and goodwill in a family loses its influence, so kinsfolk ought to carry on their mutual relations as much as possible within doors. A man should always cross himself when he steps over a threshold, and he ought not, it is believed in some places, to sit down on one. Sick children, who are supposed to have been afflicted by an evil eye, are washed on the threshold of their cottage, in order that, with the help of the Penates who reside there, the malady may be driven out of doors.

Allusion has already been made to the customs observed when a Russian peasant family is about to migrate into a new house. So strange are they, that they are well deserving of a fuller notice. After every thing movable has been taken away from the old house, the mother-in-law, or the oldest woman in the family, lights a fire for the last time in the stove. When the wood is well alight she rakes it together into the pechurka (a niche in the stove), and waits till midday. A clean jar and a white napkin have been previously provided, and in this jar, precisely at midday, she deposits the burning embers, covering them over with the napkin. She then throws open the house-door, and, turning to the “back corner,” namely to the stove, says, “Welcome, dyedushka (grandfather) to our new home!” Then she carries the fire-containing jar to the courtyard of the new dwelling, at the opened gates of which she finds the master and mistress of the house, who have come to offer bread and salt to the Domovoy. The old woman strikes the door-posts, asking, “Are the visitors welcome?” on which the heads of the family reply, with a profound obeisance, “Welcome, dyedushka, to the new spot!”

After that invitation she enters the cottage, its master preceding her with the bread and salt, places the jar on the stove, takes off the napkin and shakes it towards each of the four corners, and empties the burning embers into the pechurka. The jar is then broken, and its fragments are buried at night under the “front corner.” When distance renders it impossible to transfer fire from. the old to the new habitation, as, for instance, when the Smolensk peasants migrate to other Governments, a fire-shovel and other implements appertaining to the domestic hearth are taken instead. In the Government of Perm such “flittings” take place by night. The house-mistress covers a table with a cloth and places bread and salt on it. A candle is then lighted before the holy icons, all pray to God, and afterwards the master of the house takes down the icons, and covers them over with the front of his dress. Then he opens the door which leads into what may be called the cellar, bows down, and says, “Neighbourling, brotherling! let us go to the new home. As we have lived in the old home well and happily, so let us live also in the new one. Be kind to my cattle and family!” After this they all set off for the new house, led by the father, who carries a cock and a hen. When they arrive at the cottage they turn the fowls loose in it, and wait till the cock crows. Then the master enters, places the icons on their stand, opens the cellar-flaps, and says, “Enter, neighbourling, brotherling!” Family prayer follows, and then the mistress lays the cloth, lights the fire, and looks after her cooking arrangements. If the cock refuses to crow it is a sign of impending misfortune. These customs are all of great antiquity. The part allotted in them to the icons dates, of course, from the time in which Christianity became the religion of the country, but a similar part may formerly have been played by images of domestic gods or deified ancestors. The whole ceremony is one of the most striking relies of that heathendom which once prevailed over the entire face of the land, and which still crops up in many of its remoter districts, sometimes half concealed by a Christian garb, sometimes exposing itself in downright pagan nakedness.

The Slavic languages and their local forms have variations of the term Domovoy and alternative names to describe the household god, including:

Děd, Dĕdek, Děduška (names of this form convey the concept of “grandfather”)

Did, Didko, Diduch, Domovyk (Ukrainian)

Damavik (Belarusian)

Dedek, Djadek (Czech)

Šetek, Šotek (Bohemian)

Skřítek

Škrata, Škriatek (Slovak)

Škrat, Škratek (Slovenian)

Skrzatek, Skrzat, Skrzot (Polish)

Chozyain, Chozyainuško (Russian) (meaning literally “master” and “little master”)

Stopan (Bulgarian)

Domovníček, Hospodáříček (Bohemian)

Domaći (Croatian)

Zmek, Smok, Ćmok (snake form)

The female counterpart Domania can appear as:

Domovikha (Russian);

Damavukha (Belarusian);

Kikimora

Marukha

Volossatka

The Rusalka

Ivan Kramskoi, Русалки (Rusalki), 1871

Next in importance to the Domovoy, but far superior to him in poetic interest, is the Rusalka. The Rusalkas are female water-spirits, who occupy a position which corresponds in many respects with that filled by the elves and fairies of Western Europe. The origin of their name seems to be doubtful, but it appears to be connected with rus, an old Slavonic word for a stream, or with ruslo, the bed of a river, and with several other kindred words, such as rosá, dew, which have reference to water. They are generally represented under the form of beauteous maidens with full and snow-white bosoms, and with long and slender limbs. Their feet are small, their eyes are wild, their faces are fair to see, but their complexion is pale, their expression anxious. Their hair is long and thick and wavy, and green as is the grass. Their dress is either a covering of green leaves, or a long white shift, worn without a girdle. At times they emerge from the waters of the lake or river in which they dwell, and sit upon its banks, combing and plaiting their flowing locks, or they cling to a mill-wheel; and turn round with it amid the splash of the stream. If any one happens to approach, they fling themselves into the waters, and there divert themselves, and try to allure him to join them. Whomsoever they get hold of they tickle to death. Witches alone can bathe with them unhurt.

In certain districts bordering on the sea the people believe, or used to believe, in marine Rusalkas, who are supposed, in some places, as, for instance, about Astrakhan, to raise storms and vex shipping. But as a general rule the Rusalkas are looked upon in Russia as haunting lakes and streams, at the bottom of which they usually dwell in crystal halls, radiant with gold and silver and precious stones. Sometimes, however, they are not so sumptuously housed, but have to make for themselves nests out of straw and feathers collected during the “Green Week,” the seventh after Easter. If a Rusalka’s hair becomes dry she dies, and therefore she is generally afraid of going far from the water, unless, indeed, she has a comb with her. So long as she has a comb she can always produce a flood by passing it through her waving locks.

In some places they are fond of spinning, in others they are given to washing linen. During the week before Whitsuntide, as many songs testify, they sit upon trees, and ask for linen garments. Up to the present day, in Little-Russia, it is customary to hang on the boughs of oaks and other trees, at that time of year, shifts and rags and skeins of thread, all intended as a present to the Rusalkas. In White-Russia the peasants affirm that during that week the forests are traversed by naked women and children, and whoever meets them, if he wishes to escape a premature death, must fling them a handkerchief, or some scrap torn from his dress.

On the approach of winter the Rusalkas disappear, and do not show themselves again until it is over. In Little-Russia they are supposed to appear on the Thursday in Holy Week, a day which in olden times was dear to them, as well as to many other spiritual beings. In the Ukraine the Thursday before Whitsuntide is called the Great Day, or Easter Sunday, of the Rusalkas. During the days called the “Green Svyatki,” at Whitsuntide, when every home is adorned with boughs and green leaves, no one dares to work for fear of offending the Rusalkas. Especially must women abstain from sewing or washing linen; and men from weaving fences and the like, such occupations too closely resembling those of the supernatural weavers and washers. It is chiefly at that time that the spirits leave their watery abodes, and go strolling about the fields and forests, continuing to do so until the end of June. All that time their voices may be heard in the rustling or sighing of the breeze, and the splash of running water betrays their dancing feet. At that time the peasant-girls go into the woods, and throw garlands to the Rusalkas, asking for rich husbands in return, or float them down a stream, seeing in their movements omens of future happiness or sorrow.

After St. Peter’s day, June 29, the Rusalkas dance by night beneath the moon, and in Little-Russia and Galicia, where Rusalkas (or Mavki as they are there called) have danced, circles of darker, and of richer grass are found in the fields. Sometimes they induce a shepherd to play to them. All night long they dance to his music: in the morning a hollow marks the spot where his foot has beaten time. Sometimes a man encounters Rusalkas who begin to writhe and contort themselves after a strange fashion. Involuntarily he imitates their gestures, and for the rest of his life he is deformed, or is a victim to St. Vitus’ dance. Any one who treads upon the linen which the Rusalkas have laid out to dry loses all his strength, or becomes a cripple; those who desecrate the Rusalnaya (or Rusalkas’) week by working are punished by the loss of their cattle and poultry. At times the Rusalkas entice into their haunts both youths and maidens, and tickle them to death, or strangle or drown them.

The Rusalkas have much to do with the harvest, sometimes making it plenteous, and at other times ruining it by rain and wind. The peasants in White-Russia say that the Rusalkas dwell amid the standing corn; and in Little-Russia it is believed that on Whit-Sunday Eve they go out to the corn-fields, and there, with joyous singing and clapping of hands, they scamper through the rye or hang on to its stalks, and swing to and fro, so that the corn undulates as if beneath a strong wind.

In some parts of Russia there is performed, immediately after the end of the Whitsuntide festival, the ceremony of expelling the Rusalkas. On the first Monday of the “Peter’s Fast” a figure made of straw is draped in woman’s clothes, so as to represent a Rusalka. Afterwards a Khorovod is formed, and the assembled company go out to the fields with dance and song, she who holds the straw Rusalka in her hand bounding about in the middle of the choral circle. On arriving at the fields the singers form two bodies, one of which attacks the figure, while the other defends it. Eventually it is torn to pieces, and the straw of which it was made is thrown to the winds, after which the performers return home, saying they have expelled the Rusalka. In the Government of Tula the women and girls go out to the fields during the “Green Week,” and chase the Rusalka, who is supposed to be stealing the grain. Having made a straw figure, they take it to the banks of a stream and fling it into the water. In some districts the young people run about the fields on Whit-Sunday Eve, waving brooms, and crying, “Pursue! pursue!” There are people who affirm that they have seen the hunted Rusalkas running out of the corn-fields into the woods, and have heard their sobs and cries.

Rusalka in tree – illustration after Ivan Bibilin

Besides the full-grown Rusalkas there are little ones, having the appearance of seven-year-old girls. These are supposed, by the Russian peasants, to be the ghosts of still-born children, or such as have died before there was time to baptize them. Such children the Rusalkas are in the habit of stealing after death, taking them from their graves, or even from the cottages in which they lie, and carrying them off to their subaqueous dwellings. Every Whitsuntide, for seven successive years, the souls of these children fly about, asking to be christened. If any person who hears one of them lamenting will exclaim, “I baptize thee in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost,” the soul of that child will be saved, and will go straight to heaven. A religious service, annually performed on the first Monday of the “Peter’s Fast,” in behalf of an unbaptized child will be equally efficacious. But if the stray soul, during seven years, neither hears the baptismal formula pronounced, nor feels the effect of the divine service, it becomes enrolled for ever in the ranks of the Rusalkas. The same fate befalls those babes whom their mothers have cursed before they were born, or in the interval between their birth and their baptism. Such small Rusalkas, who abound among the Little-Russian Mavki, are evidently akin to our own fairies. Like them they make the grass grow richly where they dance, they float on the water in egg-shells, and some of them are sadly troubled by doubts about a future state. At least it is believed in the Government of Astrakhan that the sea Rusalkas come to the surface and ask mariners, “Is the end of the world near at hand?” Besides the children of whom mention has been made, women who kill themselves, and all those who are drowned, choked, or strangled, and who do not obtain Christian burial, are liable to become Rusalkas. During the Rusalka week the relatives of drowned or strangled persons go out to their graves, taking with them pancakes, and spirits, and red eggs. The eggs are broken, and the spirits poured over the graves, after which the remnants are left for the Rusalkas, these lines being sung:–

Queen Rusalka,

Maiden fair,

Do not destroy the soul,

Do not cause it to be choked,

And we will make obeisance to thee.

On the people who forget to do this the Rusalkas will wreak their vengeance. In the Saratof Government the Rusalkas are held in bad repute. There they are described as hideous, humpbacked, hairy creatures, with sharp claws, and an iron hook with which they try to seize on passers-by. If any one ventures to bathe in a river on Whit-Sunday, without having uttered a preliminary prayer, they instantly drag him down to the bottom. Or if he goes into a wood without taking a handful of wormwood (Poluin), he runs a serious risk, for the Rusalkas may ask him, “What have you got in your hands? is it Poluin or Petrushka (Parsley).” If he replies Poluin, they cry, “Hide under the tuin (hedge),” and he is safe. But if he says, Petrushka, they exclaim affectionately, “Ah! my dushka,” and begin tickling him till he foams at the mouth. In either case they seem to be greatly under the influence of rhyme.

In the vicinity of the Dnieper the peasants believe that the wild-fires which are sometimes seen at night flickering above graves, or around the tumuli called Kurgáns, or in woods and swampy places, are lighted by the Rusalkas, who wish thereby to allure incautious travellers to their ruin; but in many places these wandering “Wills o’ the Wisp ” are regarded as being the souls of unbaptized children, and so small Rusalkas themselves. In many parts of Russia the Rusalkas are represented in the songs of the people as propounding riddles to girls, and tickling and teasing those who cannot answer them. Sometimes the Rusalkas are asked similar questions, which they answer at once, being very sharp-witted.

The Servian Vilas are evidently akin to the Rusalkas, whom they equal in beauty, and generally outdo in malice. No higher compliment can be paid to a Servian maiden than to say that she is “lovely as a Vila.” But once upon a time, says a story, a proud husband boasted that his wife was “more beautiful than the white Vila.” His vaunt was overheard by the spirit, who exclaimed,–

“Show me thy love who is fairer than I, fairer than the white Vila from the hill.”

So he took his wife by the hand and led her forth, and what he had said was true. She was three times as beautiful as the Vila, and when the Vila saw that it was so, she cried out,–

“No great vaunt is it of thine, O youth, that thy love is fairer than I, the Vila from the hill. Her a mother bare, wrapped her in silken swaddling-clothes, and nourished her with a mother’s milk. But me, the Vila from the hill–me the hill itself bare, swaddled me in green leaves. The morning dew fell–nourished me the Vila; the breeze blew from the hill–rocked me the Vila.”

Poludnitsa

Another spiritual being of the same class is the Poludnitsa. Among the Lusatians, under the name of Prezpolnica or Pripolnica, she appears in the fields exactly at mid-day (in Russian, Polden or Poluden–“half-day”), holding a sickle in her hand. There she addresses any woman whom she finds tarrying afield instead of returning home for mid-day repose, and questions her on the cultivation and the spinning of flax, cutting off the head or dividing the neck of an unsatisfactory answerer. She seems to be akin to the dæmon Meridianus, “the sickness that destroyeth in the noonday.” It is worthy of remark that the Russian peasants make use of a verb, Poludnovat’, to express the action of drawing one’s last breath–“His soul in his body scarcely poludnoet,” they say. In the Government of Archangel tradition tells of “Twelve Midnight Sisters (Polunochnitsas), who attack children, and force them to cry out with pain.”

Acedia (Poludnitsa) or the Dæmon Meridianus by Pieter Breughel the Elder

The traditions of the Russian peasants people the waters with other spiritual inhabitants besides the Rusalkas. Their songs and stories often speak of the Tsar Morskoi, the Marine or Water King, who dwells in the depths of the sea, or the lake, or the pool, and who rules over the subaqueous world. To this Slavonic Neptune a family of daughters is frequently attributed, maidens of exceeding beauty, who, when they don their feather dresses, become the Swan Maidens who figure in the popular literature of so many nations. These graceful creatures, however, as well as their royal parent, belong to the realm of the peasant’s imagination rather than to that of his belief. But this is not the case with the spirits who are called Vodyanuie, the male counterparts of the Rusalkas. In them he still believes, and of them he often stands in considerable awe.

The Vodyany or Vodyanoy

The Vodyany, or Water-sprite, like his kin spirit the Domovoy, is affectionately called Dyedushka, or Grandfather, by the peasants. He generally inhabits the depths of rivers, lakes, or pools; but sometimes he dwells in swamps, and he is specially fond of taking up his quarters in a mill-stream, close to the wheel. Every mill is supposed to have a Vodyany attached to it, or several if it has more wheels than one. Consequently millers are generally obliged to be well-versed in the black art, for if they do not understand how to treat the water-spirits all will go ill with them.

Vodyanoy by Ivan Bilibin, 1934

The Vodyany is represented by the people as a naked old man, with a great paunch and a bloated face. He is much given to drinking, and delights in carouses and card-playing. He is a patron of bee-keeping, and it is customary to enclose the first swarm of the year in a bag, and to throw it, weighted with a stone, into the nearest river, as an offering to him. He who does this will flourish as a bee-master, especially if he takes a honeycomb from a hive on St. Zosima’s day, and flings it at midnight into a millstream.

The water-sprites have their subaqueous dwellings well-stocked with all sorts of cattle, which they drive out into the fields to graze by night. They have wives and children too, under the waves, the former sometimes being women who have been drowned, or whom a parent’s curse has placed within the power of the Evil One. Many a girl who has drowned herself has been turned into a Rusalka or some such being, and then has married a Vodyany. On the occasion of such a marriage, or indeed of any subaqueous wedding, the Vodyanies indulge in such revels and mad pranks that the waters are wildly agitated, and often carry away bridges or mill-dams; at least, that is how the peasants explain such accidents as arise when the snows melt and the streams wax violent. When a water-sprite’s wife is about to bear a child he assumes the appearance of an ordinary mortal, and fetches a midwife from some neighbouring village to attend her. Once a water-baby was caught by some fishermen in their nets. It splashed about joyously as long as it was in the water, but wailed sorely when it was taken into a cottage. Its capturers returned it to its father on his promising to drive plenty of fish into their nets in future–a promise which he conscientiously fulfilled. Here is one of the stories about a mixed marriage beneath the waves. Except at the end, it is very like that which forms the groundwork of Mr. Matthew Arnold’s exquisite romaunt of “The Forsaken Merman.” “Once upon a time a girl was drowned, and she lived for many years after that with a water-sprite. But one fine day she swam to the shore, and saw the red sun, and the green woods and fields, and heard the humming of insects and the distant sound of church-bells. Then a longing after her old life on earth came over her, and she could not resist the temptation. So she came out from the water, and went to her native village. But there neither her relatives nor her friends recognized her. Sadly did she return in the evening to the water-side, and passed once more into the power of the water-sprite. Two days later her mutilated corpse floated on to the sands, while the river roared and was wildly agitated. The remorseful water-sprite was lamenting his irrevocable loss.”

When a Vodyany appears in a village it is easy to recognize him, for water is always dripping from his left skirt, and the spot on which he sits instantly becomes wet. In his own realm he not only rules over all the fishes that swim, but he greatly influences the lot of fishers and mariners. Sometimes he brings them good luck; sometimes he lures them to destruction. Sometimes he gets caught in nets, but he immediately tears them asunder, and all the fish that had been enclosed in them swim out after him. A fisherman once found a dead body floating about in the water, so he took it into his boat. But to his horror the corpse suddenly came to life, uttered a wild laugh, and jumped overboard. That was one of the Vodyany’s pranks. A sportsman once waded into a river after a wounded duck. The Vodyany got hold of him by the neck, and would have pulled him under if he had not cut himself loose with his axe. When he got home his neck was all over blue marks left by the Vodyany’s fingers. Sometimes the Vodyany will jump on a horse and ride it to death; so, to keep him away while horses are fording a river, the peasants sign a cross on the water with a knife or a scythe. One should not bathe, say the peasants, without a cross round one’s neck, or after sunset. Especially dangerous is it to bathe during the week in which falls the feast of the Prophet Ilya (Elijah, formerly Rerun, the Thunderer), for then the Vodyany is on the look out for victims. During the day he generally lies at the bottom of the deep pools, but at night he sits on the shore combing his hair, or he sports in the water, diving with a splash and coming up far away; sometimes, also, he fights with the wood-sprites, the noise of their combats being heard afar off. In Bohemia fishermen are afraid of assisting a drowning man, thinking the Vodyany will be offended and will drive away the fish from their nets; and they say he often sits on the shore with a club in his hand, from which hang ribbons of various hues: with these he allures children, and those whom be gets bold of be drowns, The souls of his victims the Vodyany keeps, making them his Servants, but their bodies he allows to float to shore.

Sometimes be changes himself into a fish, generally a pike. Sometimes, also, he is represented, like the western Merman, with a fish’s tail. In the Ukraine there is a tradition that, when the sea is rough, such half-fishy “marine people” appear on the surface of the water and sing songs. The Chumaki (local carriers) go down at such times to the sea-side, and there hear those wonderful songs which they afterwards sing in the towns and villages. In other places these “sea people” are called “Pharaohs,” being supposed, like the seals in Iceland, to be the remains of that host of Pharaoh which perished in the Red Sea.

During the winter the Vodyany sleeps, but with the early spring he awakes, wrathful and hungry, and manifests his anger by various spiteful actions. In order to propitiate him the peasants in some places buy a horse, which they feed well for three days; then they tie its legs together, smear its head with honey, adorn its mane with red ribbons, attach two millstones to its neck, and at midnight fling it into an ice-hole, or, if the frost has broken up, into the middle of a river. Three days long has the Vodyany awaited his present, manifesting his impatience by groanings and upheavings of water. After he has received his due he becomes quiet. Fishermen propitiate him at the same season of the year by pouring oil on the water, begging him, as they do so, to be good to them; and millers once a year sacrifice a black pig to him. A goose, also, is generally presented to him in the middle of September, as a return for his having watched over the farmer’s ducks and geese during the summer months.

Lyeshy, the forest spirit

Leshy (aka Lesiy, Lesiye, Lyeshe, Lyeshy, Lesovik, Miehts-Hozjin) is a Slavic forest faun/satyr, similar in nature to the Polevik sprites. Illustration taken from Colin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal 1863.

As the Vodyany haunts the waters, so does the Lyeshy make the forest [Lyes] his home. He is supposed by some critics to be one of the spirits who belong to the realm of cloudland and storm, and they hold that their hypothesis is confirmed by the fact that he can assume different shapes, and alter his stature at will, at one time making himself taller than the trees of the forest, and at another shorter than the grass of the field. He often appears as a peasant dressed in a sheepskin, but ungirdled,–as is always the case with evil spirits,–and with the left skirt crossed over the right. One of his peculiarities is, that he never has any eyebrows or eyelashes. Sometimes, like a Cyclops, he has but one eye. When he appears in his own shape, and without clothes, be greatly resembles the mediaeval pictures of the devil. From his forehead spring horns, his feet are like those of a goat, his head and body are covered with shaggy hair, which is sometimes as green as that of the Rusalkas, his fingers are tipped with long claws. In the Governments of Kief and Chernigof the peasants divide the Lyeshies into two classes, belonging respectively to the woods and to the cornfields. The one consists of giants of an ashy hue; the other of beings who, before the harvest, are of the, same height as the growing corn, and, after it, dwindle away till they are no higher than the stubble.

The Lyeshy is malicious, and to those who do not conciliate him be often does much mischief. One of his tricks is to suck their milk from the cows. In the Olonetsk Government it is believed that a herdsman ought to give a cow every summer to the Lyeshy: if he fail to do so, the revengeful spirit will destroy the whole herd. In the Government of Archangel it is held that if the herdsmen succeed in pleasing the Lyeshy, he will see to the pasturing of the village cattle. In Little-Russia, on the other hand, he is supposed to be the protector of the wolves.

These wood-demons frequently quarrel among themselves, using as their weapons huge trees and masses of rock. The devastations, usually attributed to hurricanes, are in reality, the peasants say, due to these mighty combatants of the forest world. In the Archangel Government a story is told of a Lyeshy who quarrelled with two others of his race about some forest rights. A battle ensued, in which they overcame him, tied his bands so tightly together that he could not move, and then left him to his fate. A travelling merchant chanced to come that way, and released the captive demon, who was so grateful that he sent his benefactor home in a whirlwind, and did much for him afterwards. When the Lyeshy goes round to inspect his domains, the forest roars around him and the trees shake. By night he sleeps in some hut in the depths of the woods, and if by chance he finds that a belated traveller or sportsman has taken up his quarters in the refuge he had intended for himself, he strives hard to turn out the intruder, sweeping over the hut in the form of a whirlwind which makes the door rattle and the roof heave, while all around the trees bend and writhe, and a terrible howling goes through the forest. If, in spite of all these hints, the uninvited guest will not retire, he runs the risk of being lost next day in the woods, or swallowed up in a swamp.

All the birds and beasts which inhabit the forest are under the protection of the Lyeshy. His favourite is the bear, his only servant, who watches over him when he has taken too much of the strong drink he loves so well, and guards him from the assaults of the water-sprites. When the squirrels, field-mice, and some other animals go forth in troops upon their periodical migrations, the peasants explain the fact by saying that the Lyeshies are driving their flocks from one forest to another. In 1843 a great number of migrating squirrels appeared in certain districts of Russia, and the neighbouring peasants said that it was because a Lyeshy in the Vyatka Government had gambled away all his squirrels to a brother demon in that of Vologda, and the lost property was on its way to its new master. Similar gambling transactions are frequent among the water-sprites. Fishermen know at once why it is that certain fish suddenly desert particular spots. They have been staked and lost by the local Vodyany. But neither the Lyeshy nor the Vodyany will use a pack of cards in which any clubs occur. Any thing like the sign of the cross [or Perun’s hammer-mace] is distasteful to demons.

A sportsman’s success in the woods depends, to a great extent, on his treatment of the Lyeshy. In order to please that wayward spirit, he makes an offering of a piece of bread, or a pancake, sprinkled with salt, and lays it on the stump of a tree. The Perm peasants offer up prayers once a year to the Lyeshy, presenting him with a packet of leaf-tobacco, of which he is very fond. In some districts the hunters make an offering to the Lyeshy of whatever animal they first bag, leaving it for him in, an oak forest. One of the incantations intended to be used by a hunter calls upon the “Devils and Lyeshies” to drive the hares into his power, and its magic force is supposed to be so great that the wood-demons must obey.

The Lyeshy is very fond of diverting himself in the woods, springing from bough to bough, and rocking himself among the branches as if in a cradle, whence in some places he is called Zuibochnik, [Zuibka = a cradle]. At such times he makes all manner of noises, clapping his hands, shrieking with laughter, imitating the neighing of horses, the lowing of cows, the barking of’ dogs. So loud is his laughter, say the peasants, that it may be heard for versts around. In their opinion, when the winds make the woods resound, the voice of the Lyeshy may be heard in what ignorant people might think was the creaking of branches or the crashing of stems; the sounds, also, which are erroneously attributed to an echo are in reality the calls of demons, who wish to allure an unwary sportsman or woodcutter on to dangerous ground, with the intention of tickling him to death if they can get hold of him. For in this respect the Lyeshies resemble their sisters the Rusalkas.