Akelarre, the sabbath field of the Basque witches

by Benjamin Adamah · Published · Updated

Akelarre (from the Basque words aker: “billy goat” and larre: “moorland”), resulting “field of the billy goat,” evokes images of nocturnal gatherings where witches (sorginak) convene to engage in magical rites and commune with supernatural forces. It’s a place from Basque mythology. Sorginzelaia is also another term used to refer to the witches’ field.

Akelarre or aquelarre means field of the billy goat. The black billy goat was regarded sacred and was believed to ward of evil and protect the home in Basque folk belief.

The term akelarre has been integrated into Castilian Spanish (aquelarre) and, by extension, refers to gatherings of wizards and witches. Political legends, fabricated by the Inquisition to legitimize their cruel persecutions, give them the role of assistants (who are often women) to the goddess Mari in her struggle “to give a face to lies.”

However, from an anthropological perspective, akelarreak (plural in Basque) are remnants of autochthonous religious rites that were celebrated clandestinely and demonized by Catholic officials because they were not authorized by the religious authorities of the time.

The akelarreak (plural) have lots in common with the witches’ sabbaths in general. The first of these kinds of gatherings were held in Classical Greece when women, naked and drunk, went up the mountain to celebrate parties without men, while they worshipped the God Dionysus.

Similar rites are found in India and, of course, in many European countries. Best known are the witches’ sabbaths on the Blocksberg in the Harz, Germany, the island Blockula (Blåkulla in modern Swedish, translated to “Blue Hill”) and the walnut tree sabbath or treguenda in Benevento, Italy.

The Akelarre in popular legend

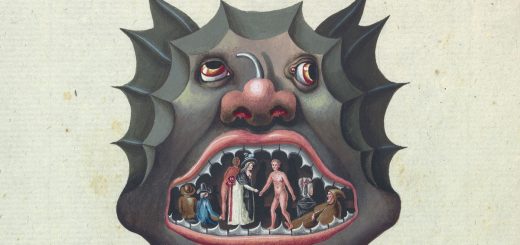

On Friday nights in a place often called Akelarre or Eperlanda (near the partridge), the sorginak celebrated magical-erotic rites. During these celebrations, cohorts of witches generally worshipped a black billy goat (akerbeltz in Basque).

One of the most well-known akelarreak was the one celebrated in the cave of Zugarramurdi (Navarre). The ritual was named after the place where it was celebrated. Akelarre is the name of the meadow located in front of said cave.

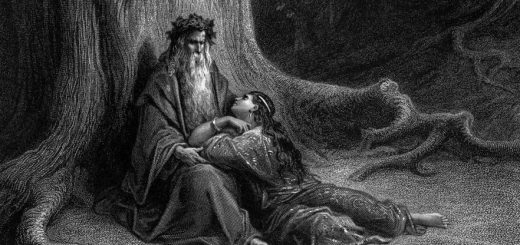

During the sabbaths, the sorginak (witches) gathered to sing, dance, play music, and feast, in akelarreak, places most often isolated and under the moonlight, all in honor of nature embodied by the Horned God or Akerbeltz.

Drugs were commonly used during these banquets and orgies because the goal was to enter into a trance to get closer to the gods. The different ways of administering hallucinogenic substances were not very well controlled. When the quantity administered could approach the lethal dose, it became very dangerous orally.

Solanaceae are plants used by the sorginak who use them with caution, as they are deadly in high doses. Thus, they made flying ointments based on animal fat to which they added mandrake, deadly nightshade, and other substances such as datura and henbane, rich in hallucinogenic substance but powerfully toxic.

The active principles of these solanaceae are tropane alkaloids. Associated with fat, this allowed rapid absorption. Once in the blood, scopolamine hit the brain and caused hallucinations similar to the sensation of flying.

That’s why these substances smeared on a broom, stick, or small brush were in the form of ointment, then applied to the vaginal mucosa or rectally. This is how the legend of witches with a broom was born. This safe way of drugging may have led to legends about the sexual nature of these witch gatherings.

The use of other utensils such as cauldrons for potion preparation, as well as ergot and toads, is part of the imagery associated with the world of witchcraft. Indeed, many poisonous toads have skin that is also hallucinogenic upon contact.

Something similar is found regarding poisonous mushrooms, such as the Amanita muscaria, better known as the “fly agaric”, associated in children’s tales with the place where genies live. Thus, the popular and international culture of representing witches with a broom between their legs would have its logical basis and origin in the Basque Country.

Historical akelarre locations

- Akelarre: A Field of Mañaria (Biscay).

- Akelarrenlezea: A large cave in Zugarramurdi (Navarre). Witches actually met outside the cave in a place called Berroskoberro. Legend has it that the goat spoke to its worshippers from a hole in the stone outside the cave. The widest part of the cave measures 120 meters, with a river known as the “river of hell” flowing through its center. Centuries of erosion have shaped the cave, with its ceiling now standing at 12 meters high. Remnants of an eighteenth-century limestone oven can still be found inside the cave, which farmers once used to extract more harvest. Another cave, the cave of the Akelarre, can be accessed from the main chamber. The name of the cave derives from the meadow at its entrance where Akelarre celebrations used to take place. Further along, the river follows a deep gorge known as “the cave of the witches.”

- Other Expressive Names for Sabbat Meeting Places in Basque Culture Include:

- Abadelaueta: In Etxaguen (Zigoitia, Alava).

- Akerlanda: Goat’s meadow, in Gautegiz Arteaga (Biscay).

- Anboto: In Durango (Biscay).

- Basajaunberro: Site of Basajaun (the wild man of the woods), in Auritz (Navarre).

- Bekatu-larre: Sinful meadow, in Ziordia (Navarre).

- Dantzaleku: Dancing place, located between Ataun and Idiazabal (Gipuzkoa).

- Edar Iturri: Beautiful Spring, in Tolosa (Gipuzkoa).

- Eperlanda: Partridges’ field, in Muxika (Biscay).

- Garaigorta: In Orozko (Biscay).

- Irantzi, Puilegi, Mairubaratza: In Oiartzun (Gipuzkoa).

- Jaizkibel Mountain: In Hondarribia (Gipuzkoa). The inquisition heard they celebrated Akelarre near the church of Santa Barbara. Local sayings believe that there were Akelarres on the bridges of Mendelu, Santa Engrazi, and Puntalea.

- Larrun Mountain: Witches from Bera (Navarre), Sara, and Azkaine (Lapurdi) gathered.

- Mandabiita: In Ataun (Gipuzkoa).

- Petralanda: In Dima (Biscay).

- Sorginerreka: Witches’ creek, in Tolosa (Gipuzkoa).

- Sorginetxe: Witches’ house, in Aia (Gipuzkoa).

- Sorgintxulo: Witches’ hole, a cave in Hernani (Gipuzkoa), and another in Ataun, both in Gipuzkoa.

- Urkitza: In Urizaharra (Alava).

A short outline of Basque Mythology

The Akelarre rituals hold a significant place in Basque folklore and mythology, representing a unique amalgamation of indigenous religious beliefs and syncretic practices. Rooted in ancient traditions, these gatherings serve as a nexus where the spiritual and the earthly converge, offering insights into the complex interplay between Basque religion and cultural expression.

At the heart of Basque religion lies a diverse pantheon of deities and spirits (ireluak), each playing a distinct role in shaping the natural world and human affairs. Central to their belief system is Mari, the goddess of the earth, fertility, and weather. Revered as both creator and destroyer, Mari embodies the dualistic forces of nature, wielding power over life and death. She is often depicted as a primordial force, residing in the depths of caves or atop sacred mountains, where she governs the cycles of the seasons and bestows blessings upon her devotees.

Alongside Mari, the Basque pantheon includes a myriad of lesser gods and spirits, such as Eguzki-Astor, the sun god, and Ilargi, the moon goddess. These celestial beings exerted influence over celestial phenomena and agricultural cycles, with rituals dedicated to appeasing their divine wrath or seeking their favor.

Additionally, Basque mythology is replete with supernatural creatures, including the Basajaunak (wild forest spirits), Lamiak (water nymphs), and Aatxegorriak (mysterious beings dwelling in mountain caves). These entities inhabited the liminal spaces of the natural world, serving as intermediaries between mortals and the divine realm.

Rituals and Ceremonies

The religious practices of the Basque people were deeply intertwined with the rhythms of agricultural life, reflecting their close connection to the land and its bounty. One of the most prominent rituals was the celebration of Akelarre, or witches’ sabbath, a nocturnal gathering where witches (sorginak) convened to commune with spirits, perform magical rites, and invoke the powers of nature. These gatherings often took place in secluded outdoor locations, such as forest clearings or remote meadows, under the cover of darkness.

Another important ceremony was the worship of jai-Alai, or sacred stones, which were believed to possess supernatural properties and serve as conduits for divine energy. These stones were adorned with offerings of food, flowers, and libations, symbolizing the reciprocal relationship between humans and the divine. Similarly, the Basque people erected dolmens and megalithic structures as sacred sites for ritualistic practices, venerating the ancestral spirits and seeking guidance from the unseen forces of the cosmos.

Zugarramurdi Witch Trials

In 1610, the Spanish Inquisition tribunal of Logroño initiated a vast witch-hunt in Zugarramurdi and the surrounding villages of Navarre, resulting in 300 individuals being accused of practicing witchcraft. Forty of them were taken to Logroño, where 12 supposed witches were burnt at the stake in Zugarramurdi (five of them symbolically, having been previously killed under torture).

Julio Caro Baroja, in his book “The World of the Witches,” explains that Basque witchcraft gained notoriety due to this witch-hunt, becoming one of the most infamous incidents in European witch-hunting history. It was likely through these significant trials that the term “akelarre” became synonymous with the concept of a “witch’s sabbath” and entered common usage in both Basque and Spanish.

While earlier studies of the Zugarramurdi trials have focused on the mechanics of persecution, recent analyses by Emma Wilby have delved into how the suspects themselves brought a diverse range of beliefs and experiences to their descriptions of the akelarre. These ranged from folk magical practices, communal medicine-making, and confraternal meetings to popular expressions of Catholic religious rituals and theatrics, such as liturgical misrule and cursing masses.

Enduring Legacy

Despite the gradual encroachment of Christianity and the suppression of indigenous beliefs by outside authorities, elements of Basque religion have persisted through the ages, embedded in the fabric of local customs and folklore. Many traditional festivals and celebrations, such as San Juan Eguna (St. John’s Day) and the Feast of San Fermin, retain traces of pre-Christian rituals and symbolism, reflecting the enduring influence of autochthonous spirituality.

While historical accounts and Christian narratives have often portrayed Akelarre gatherings as diabolical and heretical, recent scholarship suggests a more nuanced understanding of these rituals. Rather than mere acts of blasphemy or devil worship, Akelarre rituals can be seen as expressions of Basque religiosity, where elements of pagan worship and Christian symbology coalesce to create a unique spiritual experience.