Mami Wata

Mami Wata (Mammy Water) is a water spirit venerated in West, Central, and Southern Africa, and in the African diaspora in the Americas. Mami Wata spirits are usually female, but are sometimes male, something they have in common with the Undines, Nixes and other water-Elementals like Nereids etc. in European lore. The water spirit is depicted either like a mermaid or a woman holding two snakes. The looks of her hair range from straight, curly to kinky black and combed straight back.

mama wati

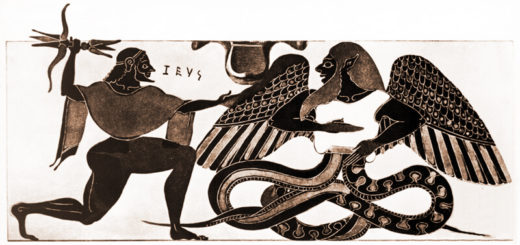

Most scholarly sources suggest the name “Mami Wata” is a pidgin English derivation of “Mother Water,” reflecting the goddess’s title (“mother of water” or “grandmother of water”) in the Agni language of Cote d’Ivoire, although this etymology has been disputed by Africanist writers in favor of various non-English etymologies, for example, the suggestion of a linguistic derivation from ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian, such as the Egyptian terms “Mami” or “Mama,” meaning “truth” “Uati” or “Uat-Ur” for “ocean water”. Historical evidence for such a deep antiquity of the goddess’s tradition demands a further research to a connection with the Mesopotamian Ea or the Syrian Atargaris. Commonly thought to be a single entity, the term Mami Wata has been applied to a number of African water deity traditions across various cultures.

Mami Wata art

The spiritual importance of Mami Wata is deeply rooted in the ancient tradition and mythology of the coastal southeastern Nigerians (Efik, Ibibio and Annang people). Mami Wata often carries expensive baubles such as combs, mirrors, and watches. A large snake (symbol of divination and divinity) frequently accompanies her, wrapping itself around her and laying its head between her breasts. Other times, she may try to pass as completely human, wandering busy markets or patronising bars. She may also manifest in a number of other forms, including as a man. Traders in the 20th century carried similar beliefs with them from Senegal to as far as Zambia.

As the Mami Wata traditions continued to re-emerge, native water deities were syncretized into it. Traditions on both sides of the Atlantic tell of the spirit abducting her followers or random people whilst they are swimming or boating. She brings them to her paradisaical realm, which may be underwater, in the spirit world, or both. Should she allow them to leave, the travellers usually return in dry clothing and with a new spiritual understanding reflected in their gaze. These returnees often grow wealthier, more attractive, and more easygoing after the encounter.

Mami Wata-worship

Mami Wata-worship is as diverse as her initiates, priesthood and worshippers, although some parallels may be drawn. Groups of people may gather in her name, but the spirit is much more prone to interacting with followers on a one-on-one basis. She thus has many priests and mediums in Africa, America and in the Caribbean who are specifically born and initiated to her. In Nigeria, devotees typically wear red and white clothing, as these colors represent that particular Mami’s dual nature. In Igbo iconography, red represents such qualities as death, destruction, heat, being male, physicality, and power. In contrast, white symbolizes death, but also can symbolize beauty, creation, being female, new life, spirituality, translucence, water, and wealth. This regalia may also include a cloth snake wrapped about the waist.

Intense dancing accompanied by musical instruments such as African guitars or harmonicas often forms the core of Mami Wata-worship. Followers dance to the point of entering a trance. At this point, Mami Wata possesses the person and speaks to him or her. Offerings to the spirit are also important, and Mami Wata prefers gifts of delicious food and drink, alcohol, fragrant objects (such as pomade, powder, incense, and soap), and expensive goods like jewelry. Modern worshippers usually leave her gifts of manufactured goods, such as Coca-Cola or designer jewelry.

According to Hounnon Behumbeza, high priest of the Mami Wata tradition in West Africa (Benin, Togo and Ghana), “The Mami Wata tradition consists of a huge pantheon of deities and spirits, not just the often portrayed mermaid”. Behumbeza goes on to say that “true knowledge and understanding of Mami Wata is shared with those initiated into the priesthood of Mami and with those who hear the calling for initiation into her mysteries.

Mami Wata ceremoni in Benin

Mami Watas’ demonic aspect

In contrast to her positive nature Mami Wata is blamed for all sorts of misfortune. In Cameroon, for example, Mami Wata is ascribed with causing the strong undertow that kills many swimmers each year along the coast. Mami Wata’s association with sex and lust is somewhat paradoxically linked to one with fidelity. According to a Nigerian tradition, male followers may encounter the spirit in the guise of a beautiful, sexually promiscuous woman, such as a prostitute. In Nigerian popular stories, Mami Wata may seduce a favored male devotee and then show herself to him following coitus. She then demands his complete sexual faithfulness and secrecy about the matter. Acceptance means wealth and fortune; rejection spells the ruin of his family, finances, and job, akin to the Melusine-folk lore of medieval France.

Mami Wata and healing

Another prominent aspect of the Mami Wata deities is their connection to healing. If someone comes down with an incurable, languorous illness, Mami Wata often takes the blame. The illness is evidence that Mami Wata has taken an interest in the afflicted person and that only she can cure him or her. Similarly, several other ailments may be attributed to the water spirit. In Nigeria, for example, she takes the blame for everything from headaches to sterility. In fact, barren mothers often call upon the spirit to cure their affliction. Many traditions hold that Mami Wata herself is barren, so if she gives a woman a child, that woman inherently becomes more distanced from the spirit’s true nature. The woman will thus be less likely to become wealthy or attractive through her devotion to Mami Wata. Images of women with children often decorate shrines to the spirit.

Mami Wata’s image shift

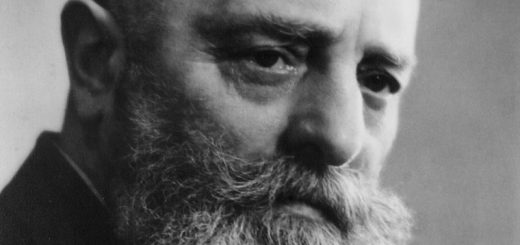

Poster of Nala Damajanti which influenced the image of Mami Wati as a woman holding two snakes instead of that of a mermaid.

As other deities become absorbed into the figure of Mami Wata, the spirit often takes on characteristics unique to a particular region or culture. In Trinidad and Tobago, for example, Maman Dlo plays the role of guardian of nature, punishing overzealous hunters or woodcutters. She is the lover of Papa Bois, a nature spirit.

In time Mami Wata image has shifted more or less from a mermaid to a snake woman which became a sort of definitive image of Mami Wata. This happened in the 19th century and there’s a strange story behind it. Circa 1887, a chromolithograph of a female Samoan snake charmer appeared in Nigeria. According to the British art historian Kenneth C. Murray, the poster was titled Der Schlangenbändiger (“The Snake Charmer”) and was originally created sometime between 1880 and 1887. Dr. Tobias Wendl, director of the Iwalewa-Haus Africa Centre at the University of Bayreuth, was unable to confirm this after extensive searching (as Der Schlangenbändiger is a masculine term, the title seems suspect). He did discover a very similar photograph titled Die samoanische Schlangenbändigerin Maladamatjaute (“the Samoan Snake Charmer (fem.) Maladamatjaute”) in the collection of the Wilhelm-Zimmermann Archive in Hamburg. Whichever the original image, it was almost certainly a poster of a celebrated late 19th-century snake charmer who performed under the stage name “Nala Damajanti”, which appeared in several variations, particularly “Maladamatjaute”, at numerous venues, including the Folies Bergère in 1886. This identification was also made by Drewal in a 2012 book chapter on Mami Wata. Despite exotic claims of her nationality, she was later identified as one Émilie Poupon of Nantey, France.

This image—an enticing woman with long, black hair and a large snake slithering up between her breasts, ambiguous if she is human or mermaid beyond the image—apparently caught the imaginations of the Africans who saw it; it was the definitive image of the spirit. Before long, Mami Wata posters appeared in over a dozen countries and the popular image was reproduced in 1955 by the Shree Ram Calendar Company in Bombay for the African market. People began creating Mami Wata art of their own, much of it influenced by the lithograph.

Mami Wata in Suriname and winti

In Dutch Guiana the spirit appears in the 1740s in the journal of an anonymous colonist: “It sometimes happens that one or the other of the black slaves either imagines truthfully, or out of rascality pretends to have seen and heard an apparition or ghost which they call water mama, which ghost would have ordered them not to work on such or such a day, but to spend it as a holy day for offering with the blood of a white hen, to sprinkle this or that at the water-side and more of that monkey-business, adding in such cases that if they do not obey this order, shortly Watermama will make their child or husband etc. die or harm them otherwise.”

Slaves worshipped the spirit by dancing and then falling into a trancelike state. In the 1770s, the Dutch rulers outlawed the ritual dances associated with the spirit. The governor, J. Nepveu, wrote: “the Papa, Nago, Arada and other slaves who commonly are brought here under the name Fida [Ouidah] slaves, have introduced certain devilish practices into their dancing, which they have transposed to all other slaves; when a certain rhythm is played… they are possessed by their god, which is generally called Watramama.”

Native Americans of the colony adopted Watermama from the slaves and merged her with their own water spirits. By the 19th century, an influx of enslaved Africans from other regions had relegated Watermama to a position in the pantheon of the deities of the Surinamese Winti religion. When Winti was outlawed in the 1970s, her religious practices lost some of their importance in Suriname.

Nigerian Folk Stories Collected From The Efik, Ibibio & People of Ikom

Loa Lasirenn

In Haiti, Lasirenn is a Voodoo loa who represents Mami Wata. She is described as a strong-willed, sensual siren who possesses the ability to drown those enticed by her. Lasirenn is often depicted as a half-fish, half-human being, but is occasionally portrayed as a whale. Similar to many other depictions of Mami Wata, Lasirenn is often shown gazing at herself in a mirror, a symbolic representation of her beauty. She is often associated with queer relationships among Black women.

See also:

Spiritual Fetichism – A Treasure Box of Magic and Spirits

Pomba Gira and Exu

Voodoo amulets and their Loas

Voodoo

Marie Laveau and the Magic of New Orleans Voodoo Queens

Umbanda, Brazilian Vodum and Santeria

Palo and Hoodoo

Charms to avoid injuries and gain psychic power

Potent Clove and the power of Bluestone