Grimoires or instruction books on magic

A grimoire is a textbook of magic, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans and amulets, how to perform magical spells, charms and divination, and how to summon or invoke supernatural entities such as angels, spirits, deities and demons. In many cases, the books themselves are believed to be imbued with magical powers, although in many cultures, other sacred texts that are not grimoires (such as the Bible) have been believed to have supernatural properties intrinsically. In this manner, while all books on magic could be thought of as grimoires, not all magical books should be thought of as grimoires.

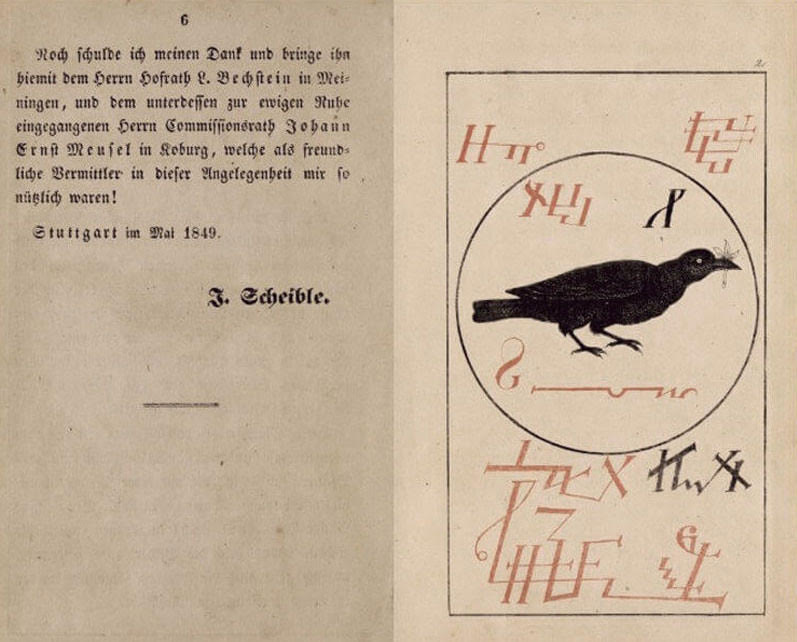

Magia Naturalis et Innaturalis by Johannus Faust was first published in 1505 and republished in 1849 in Stuttgart by J. Scheible

While the term grimoire is originally European and many Europeans throughout history, particularly ceremonial magicians and cunning folk, have used grimoires, the historian Owen Davies noted that similar books can be found all across the world, ranging from Jamaica to Sumatra. He also noted that in this sense, the world’s first grimoires were created in Europe and the Ancient Near East. Owen Davies, professor of social history at the University of Hertfordshire, has written extensively about the history of magic, witchcraft and ghosts and published a Grimoire Top 10 in the Guardian, based on popular use:

1. The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses

Although one of the more recent grimoires, first circulating in manuscript in the 18th century, this has to be number one for the breadth of its influence. From Germany it spread to America via the Pennsylvania Dutch, and once in cheap print was subsequently adopted by African Americans. With its pseudo-Hebraic mystical symbols, spirit conjurations and psalms, this book of the secret wisdom of Moses was a founding text of Rastafarianism and various religious movements in west Africa, as well as a cause célèbre in post-war Germany.

2. The Clavicule of Solomon

This is the granddaddy of grimoires. Mystical books purporting to be written by King Solomon were already circulating in the eastern Mediterranean during the first few centuries AD. By the 15th century hundreds of copies were in the hands of Western scientists and clergymen. While some denounced these Solomonic texts as heretical, many clergymen secretly pored over them. Some had lofty ambitions to obtain wisdom from the “wisest of the wise”, while others sought to enrich themselves by discovering treasures and vanquishing the spirits that guarded them.

3. Petit Albert

The “Little Albert” symbolises the huge cultural impact of the cheap print revolution of the early 18th century. The flood gates of magical knowledge were opened during the so-called Enlightenment and the Petit Albert became a name to conjure with across France and its overseas colonies. As well as practical household tips it included spells to catch fish, charms for healing, and instructions on how to make a Hand of Glory, which would render one invisible.

4. The Book of St Cyprian

Grimoires purporting to have been written by a legendary St Cyprian (there was a real St Cyprian as well) became popular in Scandinavia during the late 18th century, while in Spain and Portugal print editions of the Libro de San Cipriano included a gazetteer to treasure sites and the magical means to obtain their hidden riches. During the early 20th century, editions began to appear in South America, and copies can now be purchased from the streets of Mexico City to herbalist stalls high in the Andes.

5. Dragon rouge

Like the Petit Albert, the Red Dragon was another product of the French cheap grimoire boom of the 18th century. Although first published in the following century, it was basically a version of the Grand grimoire, an earlier magic book which was infamous for including an invocation of the Devil and his lieutenants. The Dragon rouge circulated far more widely though, and is well known today in former and current French colonies in the Caribbean.

6. The Book of Honorius

Books attributed to Honorius of Thebes were second only to those of Solomon in notoriety in the medieval period. In keeping with a strong theme in grimoire history, there is no evidence that an arch magician named Honorius lived in antiquity – as manuscripts ascribed to him stated. Through prayers and invocations, books of Honorius gave instructions on how to receive visions of God, Hell and purgatory, and knowledge of all science. Very handy.

7. The Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy

Cornelius Agrippa was one of the most influential occult philosophers of the 16th century. He certainly wrote three books on the occult sciences, but he had nothing to do with the Fourth Book which appeared shortly after his death. This book of spirit conjuration blackened the name of Agrippa at a time when the witch trials were being stoked across Europe.

8. The Magus

Published in 1801 and written by the British occultist and disaster-prone balloonist Francis Barrett, The Magus was a re-statement of 17th-century occult science, and borrowed heavily from an English edition of the Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy. It was a flop at the time but its influence was subsequently considerable on the occult revival of the late 19th century and contemporary magical traditions. In the early 20th century a plagiarised version produced by an American occult entrepreneur and entitled The Great Book of Magical Art, Hindu Magic and East Indian Occultism became much sought after in the US and the Caribbean.

9. The Necronomicon

A figment of the ingenious imagination of the influential early 20th-century writer of horror and fantasy HP Lovecraft, this mysterious book of secret wisdom was penned in the eighth century by a mad Yemeni poet. Despite being a literary fiction, several “real” Necronomicons have been published over the decades, and today it has as much a right to be considered a grimoire as the other entries in this Top 10.

10. Book of Shadows

Last but not least there is the founding text of modern Wicca – a pagan religion founded in the 1940s by the retired civil servant, folklorist, freemason and occultist Gerald Gardner. He claimed to have received a copy of this “ancient” magical text from a secret coven of witches, one of the last of a line of worshippers of an ancient fertility religion, which he and his followers believed had survived centuries of persecution by Christian authorities. Through its mention in such popular occult television dramas as Charmed, it has achieved considerable cultural recognition.

the Guardian, April 8, 2009

Historical List of Classic GrimoiresTestament of Solomon (3rd century or older) |

Azeruel from one of Dr. Johann Faust’s grimoires: Magia Naturalis et Innaturalis

Page from a French edition of the Greater Key of Solomon |

Etymology

It is most commonly believed that the term grimoire originated from the Old French word grammaire, which had initially been used to refer to all books written in Latin. By the 18th century, the term had gained its now common usage in France, and had begun to be used to refer purely to books of magic. Owen Davies presumed this was because “many of them continued to circulate in Latin manuscripts”.

However, the term grimoire later developed into a figure of speech amongst the French indicating something that was hard to understand. In the 19th century, with the increasing interest in occultism amongst the British following the publication of Francis Barrett’s The Magus (1801), the term entered the English language in reference to books of magic.

History

Ancient period

The earliest known written magical incantations come from ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), where they have been found inscribed on cuneiform clay tablets that archaeologists excavated from the city of Uruk and dated to between the 5th and 4th centuries BC. The ancient Egyptians also employed magical incantations, which have been found inscribed on amulets and other items. The Egyptian magical system, known as heka, was greatly altered and enhanced after the Macedonians, led by Alexander the Great, invaded Egypt in 332 BC.

Under the next three centuries of Hellenistic Egypt, the Coptic writing system evolved, and the Library of Alexandria was opened. This likely had an influence upon books of magic, with the trend on known incantations switching from simple health and protection charms to more specific things, such as financial success and sexual fulfillment. Around this time the legendary figure of Hermes Trismegistus developed as a conflation of the Egyptian god Thoth and the Greek Hermes; this figure was associated with writing and magic and, therefore, of books on magic.

The ancient Greeks and Romans believed that books on magic were invented by the Persians. The 1st-century AD writer Pliny the Elder stated that magic had been first discovered by the ancient philosopher Zoroaster around the year 647 BC but that it was only written down in the 5th century BC by the magician Osthanes. His claims are not, however, supported by modern historians.

The appearences of the seven great Fire-spirits – the 1849 edition of Magia Naturalis et Innaturalis attributed to Faust.

The ancient Jewish people were often viewed as being knowledgeable in magic, which, according to legend, they had learned from Moses, who had learned it in Egypt. Among many ancient writers, Moses was seen as an Egyptian rather than a Jew. Two manuscripts likely dating to the 4th century, both of which purport to be the legendary eighth Book of Moses (the first five being the initial books in the Biblical Old Testament), present him as a polytheist who explained how to conjure gods and subdue demons.

Meanwhile, there is definite evidence of grimoires being used by certain, particularly Gnostic, sects of early Christianity. In the Book of Enoch found within the Dead Sea Scrolls, for instance, there is information on astrology and the angels. In possible connection with the Book of Enoch, the idea of Enoch and his great-grandson Noah having some involvement with books of magic given to them by angels continued through to the medieval period.

Israelite King Solomon was a Biblical figure associated with magic and sorcery in the ancient world. The 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian Josephus mentioned a book circulating under the name of Solomon that contained incantations for summoning demons and described how a Jew called Eleazar used it to cure cases of possession. The book may have been the Testament of Solomon but was more probably a different work. The pseudepigraphic Testament of Solomon is one of the oldest magical texts. It is a Greek manuscript attributed to Solomon and likely written in either Babylonia or Egypt sometime in the first five centuries AD, over 1,000 years after Solomon’s death.

The work tells of the building of The Temple and relates that construction was hampered by demons until the angel Michael gave the king a magical ring. The ring, engraved with the Seal of Solomon, had the power to bind demons from doing harm. Solomon used it to lock demons in jars and commanded others to do his bidding, although eventually, according to the Testament, he was tempted into worshiping “false gods”, such as Moloch, Baal, and Rapha. Subsequently, after losing favour with God, King Solomon wrote the work as a warning and a guide to the reader.

When Christianity became the dominant faith of the Roman Empire, the early Church frowned upon the propagation of books on magic, connecting it with paganism, and burned books of magic. The New Testament records that after the unsuccessful exorcism by the seven sons of Sceva became known, many converts decided to burn their own magic and pagan books in the city of Ephesus; this advice was adopted on a large scale after the Christian ascent to power

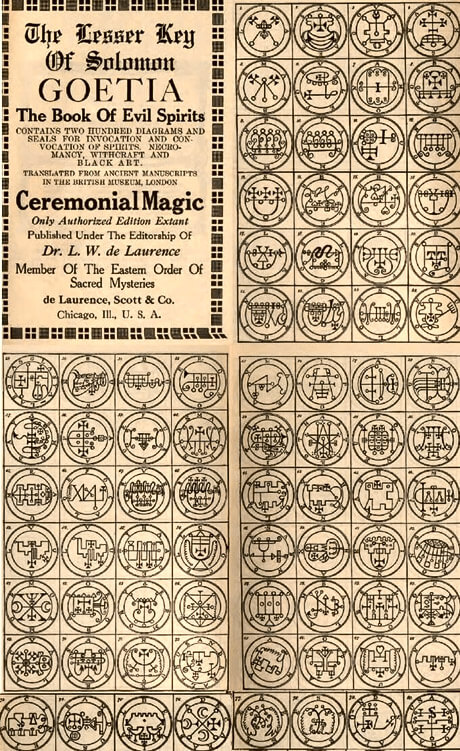

Page with the sigils of the goetic demons.

Medieval period

In the Medieval period, the production of grimoires continued in Christendom, as well as amongst Jews and the followers of the newly founded Islamic faith. As the historian Owen Davies noted, “while the [Christian] Church was ultimately successful in defeating pagan worship it never managed to demarcate clearly and maintain a line of practice between religious devotion and magic.” The use of such books on magic continued. In Christianised Europe, the Church divided books of magic into two kinds: those that dealt with “natural magic” and those that dealt in “demonic magic”.

The former was acceptable because it was viewed as merely taking note of the powers in nature that were created by God; for instance, the Anglo-Saxon leechbooks, which contained simple spells for medicinal purposes, were tolerated. Demonic magic was not acceptable, because it was believed that such magic did not come from God, but from the Devil and his demons. These grimoires dealt in such topics as necromancy, divination and demonology. Despite this, “there is ample evidence that the mediaeval clergy were the main practitioners of magic and therefore the owners, transcribers, and circulators of grimoires,” while several grimoires were attributed to Popes.

One such Arabic grimoire devoted to astral magic, the 12th-century Ghâyat al-Hakîm fi’l-sihr, was later translated into Latin and circulated in Europe during the 13th century under the name of the Picatrix. However, not all such grimoires of this era were based upon Arabic sources. The 13th-century Sworn Book of Honorius, for instance, was (like the ancient Testament of Solomon before it) largely based on the supposed teachings of the Biblical king Solomon and included ideas such as prayers and a ritual circle, with the mystical purpose of having visions of God, Hell, and Purgatory and gaining much wisdom and knowledge as a result. Another was the Hebrew Sefer Raziel Ha-Malakh, translated in Europe as the Liber Razielis Archangeli.

A later book also claiming to have been written by Solomon was originally written in Greek during the 15th century, where it was known as the Magical Treatise of Solomon or the Little Key of the Whole Art of Hygromancy, Found by Several Craftsmen and by the Holy Prophet Solomon. In the 16th century, this work had been translated into Latin and Italian, being renamed the Clavicula Salomonis, or the Key of Solomon.

In Christendom during the medieval age, grimoires were written that were attributed to other ancient figures, thereby supposedly giving them a sense of authenticity because of their antiquity. The German abbot and occultist Trithemius (1462–1516) supposedly had a Book of Simon the Magician, based upon the New Testament figure of Simon Magus. Simon Magus had been a contemporary of Jesus Christ’s and, like the Biblical Jesus, had supposedly performed miracles, but had been demonized by the Medieval Church as a devil worshiper and evil individual.

Similarly, it was commonly believed by medieval people that other ancient figures, such as the poet Virgil, astronomer Ptolemy and philosopher Aristotle, had been involved in magic, and grimoires claiming to have been written by them were circulated. However, there were those who did not believe this; for instance, the Franciscan friar Roger Bacon (c. 1214–94) stated that books falsely claiming to be by ancient authors “ought to be prohibited by law.

Early modern times

In the time of the Reformation and Humanism, the Grimoires mainly dealt with Jewish and Arabic religious philosophy, as well as Kabbalah. Especially the kabbalistic writings of rabbis from the ancient Hebrew writings became a model for magic means and rites. In 1565, the first part of the Arbatel book, consisting of nine parts, was printed and published under the fourth volume of the writings of Agrippa von Nettesheim. A collection of writings not from Agrippa itself, but from the publisher of the time either for economic reasons with Agrippa’s name in print or actually from the library estate of Agrippa were given. Johann Weyer or the Inquisitor Delrio publish works in which they wrote about the black books, the so-called Libri Nigri. By dealing with these writings, the scholars themselves were always exposed to the accusation of heresy and heresy.

From the 16th century onwards, the younger Clavicula Salomonis, Salomonis et Semiphoras and the Grimorium Verum followed. However, in the course of time the original content of the grimoires degenerated more and more into pure protection and treasure books. A distortion from this time are the hell compulsions attributed to Dr. Faust (Dr. Faust’s Great and Powerful Compulsion with Hell, Dr. Faust’s Fourfold Compulsion with Hell, Dr. Faust’s Miracle, Art and Wonder Book or the Black Raven, Dr. Faust’s Great and Powerful Sea Spirit and Faust’s Triple Compulsion with Hell). The same goes for the French Dragon Rouge and the German translation, The Truly Fiery Dragon.

The Grimoires were passed on from generation to generation and revised according to epoch and need. Recipes were changed and supplemented and new instructions were constantly added. In the 18th century, the Egyptian Secrets of Albertus Magnus, the Black Hen and The Sixth and Seventh Book of Moses appeared.

Starting from France in the Napoleonic era, Grimoires spread increasingly to other European countries. The Philosophical Merlin published in 1822 is the first English Grimoire of the modern era. It refers in its authorship to Napoleon Bonaparte, works up mainly French sources and offers additionally an astrological system, similar to the Chinese I-Ging.

Industrial age

From the 19th century onwards, collections of various magical manuscripts and grimoires were published, which were merely a reproduction of the old magic books, but were thus made accessible to a broad public and preserved for posterity: Horst’s magical library, the Scheible publishing house’s collection of the greatest secrets of extraordinary people in ancient times and the volumes Das Kloster. Occult associations, such as the Ordo Templi Orientis or the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, have given rise to such famous people as Aleister Crowley and William Wynn Westcott. Some works of these occultists also belong to the Grimoires, such as Crowley’s Liber Samekh.

In Germany between the two world wars the release of Grimoires with mostly strongly changed lyrics increased again. Due to political turmoil, inflation and mass unemployment, those affected resorted to the newly published magic books, which were published by enterprising publishers in large editions. In the early decades of the 20th century the newly written 8th to 13th books of Moses and the collection of magical writings, the book Jezira (not to be confused with the Sepher Jezirah from the 9th century) appeared. With the new religions also in the 20th century the Wicca witches developed the concept of the Book of Shadows. Mysterious books, such as the Necronomicon, a fictional grimoire by H. P. Lovecraft, occupy a special position. Sometimes the Voynich manuscript, which could not be deciphered until today, is called Grimoire.

Part of 18th typical century grimoire with “Agrippa’s” square of Mercury and Mercury-planet-angel Raphael.

20th and 21th Century

In particular, the second half of the 20th century shows a resurgence of interest in Grimoires. The best-known representative of this trend is Simon Necronomicon, who reworked the works of H. P. Lovecraft and Aleister Crowley, but presented himself as an antique typeface. The Simon Necronomicon tells the story of a “crazy Arab” who turned away from Islam to find the traces of the Sumerians and their gods in the desert. Embedded in this framework plot, the book illuminates incantations and seals that reveal clear references to earlier works. This is why, despite its high popularity, the work is seen as controversial and denied authenticity in the sense of a genuinely rediscovered ancient script.

The Azoëtia by Andrew D. Chumbley is less well-known and can be classified in the traditional English tradition, albeit not Wicca. In contrast to other works such as the aforementioned Simon Necronomicon or the older Lemegeton Clavicula Salomonis, it does not present itself as a rediscovered ancient script, but as a modern grimoire. Totally overshadowed in the occult world in general are 20th century grimoires, many of them excellent, of Germany and German speaking countries. Great names as Franz Bardon, the Berlin magician H.E. Douval, Brandler-Pracht, Karl Spiesberger, Rah Omir Quintscher, Dr. Musallam, should not be missing in any overview nor several grimoires produced bij German lodges as the Fraternitas Saturni, founded by Gregor A. Gregorius and the notorious FOCG.

When applying a more loose definiton of the grimoire, interesting things are happening in the US (with magic and sorcery specialists as A.E. Koeting, Jason Miller, Catherine Ironwode (hoodoo) and John Kreiter) and Australia (OBE specialist Robert Bruce). Very valuable revised and/or restored and/or completed classic grimoires are produced by Joseph Peterson and Stephen Skinner. They combine an academic level with being practising magicians themselves.

Categories of grimoires

The Grimoires can roughly be divided into categories.

- Black Magic Grimoires: Often written anonymously or under a pseudonym, these are writings that contain baneful spells, demon summoning, necromancy, or the summoning of Lucifer, such as Clavicula Salomonis, Grimorium Verum, or Grand Grimoire.

- Philosophical Grimoires: Most well-known authors, such as John Dee, Agrippa von Nettesheim or Gerhard von Cremona, deal scientifically with magic. The topics are the magia naturalis, occult sciences, the Kabbalah, alchemy, as well as detailed and mostly newly developed incantation techniques. They are so to speak textbooks of magic (De Occulta Philosophia, Liber Loagaeth, Book Abramelin etc.).

- Magic prayer books: These Grimoires, which are attributed to the church, are very numerous. Published under the names of popes or clergymen, these books contain invocations to saints, magical prayers, numerous protective evocations as well as invocations of angels, but also of spirits (Geistlicher Schild, Romanusbüchlein, Das Christoph-Gebet etc.).

- Grimoires of popular belief: Mostly Christian-magical grimoires mixed with popular superstitions. Mostly summons to demons and protection prayers to God and saints, so that one can reach wealth, destroy the enemy or maintain health (The Golden Fountain, Habermann, St. Corona’s Treasure Prayer etc.).

- magic recipe books: books with strange magic recipes against illness, to protect against enemies, for wealth, love etc. (The sixth and seventh book of Mosis, Egyptian secrets, Mysterious hero treasure, Secret art school of magical miracle powers etc.).

Almost all magic writings have in common the desire to protect themselves from threatening disaster and danger, to gain strength and health, to see the future and above all to achieve wealth. It is striking that no author can be found in many works. One reason for this is that authors had to expect to be burnt at the stake because magic was forbidden by the Inquisition. For this reason, many Grimoires were published under well-known names such as Albertus Magnus or Paracelsus. Also fictitious names, like a certain Alibeck (alleged author of the Grimorium Verum) or J. A. Herpentil were used for self-protection. To emphasize the importance of the work, legendary persons such as Faust, Salomon or Moses were also used. Many of these Grimoires are works by clergymen of the well-known church orders, which is documented, for example, by the works of the clergyman Éliphas Lévi. Helena Blavatsky describes adepts, necromancers and rituals in such a way that the image of the priest and his ritualized actions are created. Many rituals are based on the Holy Mass.

Many Grimoires are structurally comparable and usually follow a scheme:

- The preparation of the magician (fasting, praying, smoking, washing, etc.)

- Production of magic instruments (magic wand, robe, knife etc.)

- The magic circle

- The Book of Spirits / Liber Spirituum

- Ranking of Demons, Their Seals, Summons and Dismissals

- Spell recipes as attachments: love spells, treasure spells, divination etc.

Physically and psychologically, the magician must be cleansed of everything, and the instruments must be rebuilt and used unused. After preparation through ascetic rituals, the magician can summon different demons, devils or angels. The protective circle protects the magician from the summoned powers. Often a pact is made in which all summoned spirits must sign their seal and image as well as obedience.

The demons are often subject to a fixed hierarchy (emperor, king, prince etc.). In the Grimoires there are different versions of these rankings, which function as counter drafts of the angel structures. The different lists of demons can be explained by the fact that the lists in the respective epochs correspond to the social structure of the time. Also the number of the hell lords in the magic literature is different. A part of the hell constraints contains only the treasure bringer Azazel, the Faustian and Jesuit hell constraints first have a four-order, others often a six-order and further a seven-order, which goes back to Kabbalistic and neuplatonic roots.

sources:

Wikipedia.de

the Guardian

Wikipedia.org

You may also like to read:

Witches ointment

Why did Witches Want to Ride their Broomsticks?

The incubus or succubus – nightmare or astral sex date?

Hecate – The Calling of the Crossroad Goddess

The Ancient Witch-Cult of The Basques

Walpurgis Night

Stefan Eggeler: Walpurgis Night witches, Kokain (Cocaine) and other illustrations

Rosaleen Norton, Daughter of Pan

Mysteries of the Ancient Oaks

Black Cat Superstitions

The Mystical Mandrake

Little Secrets of the Poppy

Datura stramonium or jimson weed or zombi-cucumber

Mountain spirits

Wild Man or Woodwose

Sprite