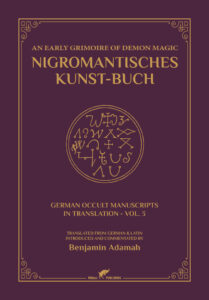

Charles Godfrey Leland, the American folklorist who saved European witchcraft

Until 1951, England had laws strictly prohibiting the practice of witchcraft. The Witchcraft Laws of June, 1 1653 stated that any form of witchcraft-related activity was prohibited. Three years after the last law was repealed, Gerald Gardner published Witchcraft Today in 1954, bringing witchcraft back into the open without threat of prosecution. But in contrast to the general assumption, the “Father of modern Wicca” was not the first to put forward the term “Wicca”. Gardner was heavily influenced by Charles Godfrey Leland, whose books he had read, including Leland’s Gypsy Sorcery and Fortune Telling (1891).

In the notes section of Chapter IV in Gypsy Sorcery and Fortune Telling we read: “Witch. Mediaeval English wicche, both masculine and feminine, a wizard, a witch. Anglo-Saxon wicca, masculine, wice, feminine. Wicca is a corruption of wítga, commonly used as a short form of witega, a prophet, seer, magician, or sorcerer. Anglo-Saxon witan, to see, allied to wítan, to know. Similarly Icelandic vitki, a wizard, is from vita, to know. Wizard, Norman-French wischard, the original Old French being guiscart, sagacious. Icelandic, vizkr, clever or knowing, . . . with French suffix ard as German hart, hard, strong” (SKEAT, “Etymol. Dictionary”). That is wiz-ard, very wife. Wit and wisdom here are near allied to witchcraft, and thin partitions do the bounds divide.”

Biography Charles Godfrey Leland

Charles Godfrey Leland

Charles Godfrey Leland (August 15, 1824 – March 20, 1903) was an American folklorist, born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Leland told the story that shortly after his birth, his old Dutch nanny took him to the family attic and performed a ritual, involving a Bible, a key, a knife, lighted candles, money and salt to ensure a long life as a “scholar and a wizard”.

The family being prosperous, employed several servants. One of them was an Irish immigrant by whom he learned about ghosts, witches and fairies. There was also a black servant, working in the kitchen who introduced him into Voodoo. His mother often referred to an ancestress that had married into “sorcery”. Anecdotes his biographers have commented upon as foreshadowing his passionate interest in folk traditions and the magical.

Charles Godfrey Leland wrote several classic books on Gypsies and Italian Witches. These include: Legends of Florence Collected from the People (two volumes), Etruscan Roman Remains in Popular Tradition and The Gypsies and Gypsy Sorcery. His book Aradia – Gospel of the Witches became one of the most influential works to affect and influence modern witchcraft, Wicca and paganism. Both Gardner and Doreen Valiente were deeply inspired by Leland.

‘Leland studied languages at Princeton University, wrote poetry, and pursued a variety of other interests, including hermeticism, Neo-Platonism, and the works of Rabelais.’

He studied languages at Princeton University, wrote poetry, and pursued a variety of other interests, including hermeticism, Neo-Platonism, and the works of Rabelais. He went to Europe to continue his studies and first attended college at Heidelberg and Munich. In 1848 he moved to Paris to analyse at the Sorbonne. The same year he got involved in the revolution as the leader of a group of Revolutionaries, constructing barricades not far from the hotel he was staying. He returned to America after the money, given to him by his father to travel, had run out.

Back home in Philadelphia, and under pressure of his pragmatic father, Leland apprenticed in a law firm. However, this law firm was no match for his curious mind and adventurous spirit and in 1853 he started a career in journalism. Leland wrote hundreds of essays, articles and reviews for some of the major periodicals of the time, including Vanity Fair and the Knickerbocker Magazine. He also wrote for the Illustrated News in New York, the Evening Bulletin in Philadelphia and eventually took on editorial duties from the Philadelphia Press, Graham’s Magazine and the Continental Monthly, a pro-Union Army publication. He joined the Union Army in 1863, and fought at the Battle of Gettysburg.

In 1856 Leland had married Isabel Fisher. After the war Leland travelled extensively throughout America, developing his knowledge of folklore. He lived and studied with the Algonquin Indians for months, recording their stories, myths and legends which he later published in his work Algonquin Legends (1884).

‘It was here in Italy he began his in-depth study of “Stregheria” or Italian Witchcraft.’

Charles Godfrey Leland returned to Europe in 1869, eventually settling in London. In 1888 he moved to Florence, where he lived for the rest of his life. It was here in Italy he began his in-depth study of “Stregheria” or Italian Witchcraft.

Stregeria ring 17th century

Less than a year after his wife passed away, Leland died on the 20th of March 1903 due to pneumonia resulting in heart problems. He was cremated in Florence and his ashes returned to America to be buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia.

Elizabeth Robins Pennell, Leland’s niece wrote a two-volume biography of him: Charles Godfrey Leland: a Biography (Boston 1906). Her biography is filled with comments on his early passionate interests in witchcraft, magic and the occult. Of his passion she writes: ‘As might be expected of the man who was called “Master” by the Witches and Gypsies, and whose pockets were always full of charms and amulets, who owned the Black Stone of the Voodoo’s, who could not see a bit of red string at his feet and not pick it up, or find a pebble with a hole in it and not add it to his store – who in a word, not only studied witchcraft with the impersonal curiosity of the scholar, but practiced with the zest of the initiated.’

Gerald Gardner posing in a magical circle

Other publications by Charles Godfrey Leland:

• Meister Karl’s Sketch-book (1855)

• Legends of Birds (1864)

• Hans Breitmann’s Ballads (1871)

• Pidgin-English Sing-Song (1872)

• The English Gipsies (1873)

• Fusang or the Discovery of America by Chinese Buddhist Priests in the Fifth Century (1875)

• Johnnykin and the Goblins (1879)

• The Gypsies (1882)

• Algonquin Legends (1884)

• Gypsy Sorcery and Fortune Telling (1891)

• The Hundred Riddles of the Fairy Bellaria (1892)

• Etruscan Roman Remains in Popular Tradition (1892)

• Leather Work, A Practical Manual for Learners (1892)

• Songs of the Sea and Lays of the Land (1895)

• Legends of Florence Collected from the People (2 vols.) (1896)

• Unpublished Legends of Virgil (1899)

• Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches (1899)

• Have You a Strong Will? (1899)

• Legends of Virgil (1901)

• Flaxius, or Leaves from the Life of an Immortal (1902)

“Witch informant” Maddalena

“Witch informant” Maddalena

Charles Godfrey Leland’s greatest source of information came from a stregha called Maddalena, who worked as a Tarot fortune teller in the back streets of Florence. She introduced him to another Tuscan witch called Marietta, who also helped the author with material for his research. Leland employed Maddalena as his personal research assistant and she passed on to him more than 200 pages of written folklore, incantations and stories. It was Maddalena, who provided Leland with the material for his most famous book Aradia – or the Gospel of the Witches. Until then, no other book could claim material obtained directly from a practicing witch. Leland described Maddalena as a woman with an inexhaustible memory who could recall a sheer endless row of incantations of Etruscan origin.

Witchcraft before Wicca

Though Aradia’s authenticity has subsequently been disputed by other folklorists and historians, the real witchcraft controversy had to wait for Margareth Murray’s classic, The Witch Cult in Western Europe. Many of the old medical treatments and magical rituals, performed by Tuscan witches, Leland discovered to be similar to those used by the ancient Etruscans of the early centuries BC. Therefore, providing a substantial support for the theory of an ongoing witch tradition dating back to Antiquity.

Gerald Gardner, perhaps not the godfather of the Wiccan movement and the birth of modern witchcraft, but it’s catalyst, supported this theory. So did Alex Sanders and Austin Osman Spare, whose tutor he said was a descendent of a Salem witch trials survivor called Mrs. Patterson. More recently, discovered Medieval documents point in the same direction and we know for certain the worship of witch goddess Diana lasted until 1647. Then there are striking parallels between today’s witchcraft in India for example and witchcraft rituals portrayed by writers and engravers in Europe during the Burning Times.

Carlo Ginzburg’s research on the Benedanti and Maledanti in Northern Italy ads an extra dimension to this discussion, as do Leonardo DaVinci, with one of his most mysterious etchings and the Basque researcher Gulio Caro Baroja with his treatment of Basque witches in The World of the Witches (1964).

Within this enervating context the works on stregheria of Leland are must reads which have lost nothing of their importance. Their uniqueness lies in Leland’s informants Maddalena and Marrietta, providing him with first hand material. Just like Thomas Hauschild recently used authentic local material for his book Magie und Macht in Italien.

Supportive of the above is this most intriguing list on the next page, with historical facts on the continuation of the witch phenomenon, or Diana worship by witches or the common pagan folk in certain regions.

Historical facts:

Diana / Artemis, goddess of hunters, outlaws and witchcraft

• The Roman historian Varro 116 – 27 BC mentions Diana worship by Titus Tatius (died 748 BC). Diana Lucina and Luna are mentioned as separate deities.

• Tullus Hostilius (third Roman king, r. 673 BC – 642 BC), in his Lex Regia condemns those guilty of incest to the sacratio to the goddess Diana.

• Diana was worshipped at a festival on August 13, when King Servius Tullius (r. 578 – 535 BC), himself born a slave, dedicated her temple on the Aventine Hill in the mid-6th century

BC. Being placed on the Aventine, and thus outside the pomerium, meant that Diana’s cult essentially remained a foreign one.

‘30 BC: First association of Diana with witches in a mystery cult in the Epodes of Horatio.’

• Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 BC – 43 BC), like Varro, links the etymology of Diana to the shine of the Moon.

• 30 BC: First association of Diana with witches in a mystery cult in the Epodes of Horatio.

• 314 AD: The Council of Ancyra (Ankara) labels witches who believe they belong to a Society of Diana as heretics. According to the Council Satan has deceived them. At night a large group of them rides with Diana or Herodias on animals.

• Saint Augustine (354 – 430), who lived in North Africa and Italy writes that amulets are worthless without the pact with a demon. It is the first record in history of the demon-pact, so often mentioned in later centuries during the witch persecutions.

• 550 AD: The Gothic historian Jordanus, in his Getica, mentions the Gothic king Filimer chasing witches (Alirunen) in the woods because they practiced divinatory arts and spoiled the country. In the woods these witches mated with satyrs.

• 662: Saint Barbato converts the Duke of Benevento, Romuald to Christianity. At Saint Barbato’s request, Romuald has the witches’ walnut tree cut down. This walnut tree is the gathering place of witches who worship Diana.

• 680: Saint Barbato attends the Council of Constantinople, where he speaks out against the witches of Benevento.

• Of St. Guthlac (683 – 714) it is reported he participated in the Wild Hunt (led by the Northern versions of Diana).

• 906: Regino of Prum, in his instructions to the Bishops, claims that pagans worship Diana in a cult called the Society of Diana.

• 1006: The 19th book of the Decretum associates the worship of Diana with the common pagan folk.

• Bishop Burckhard von Worms (965 – 1025) writes in his Bußbuch (Book of Punishment) about “criminal”women who cross the fields, in the silence of the night, riding on animals with their goddess Diana, after being seduced to such action by demons. He also complains about the fact many, belonging to the common folk, believe Diana is real, thus not restricting themselves to the Christian belief in just one God.

• Hereward the Wake (died 1070) was reported to have participated in the Wild Hunt.

• Hugues of Saint Victor (1096 – 1141), a Saxon canon regular and a leading writer on mystical theology quoted the Canon Episcopi as reading Diana Minerva. Later collections included the names Benzozia and Bizazia.

‘1310: The Council of Trier associates witches with the Goddess Diana.’

• 1280: The Diocesan Council of Conserans associates the “witch cult” with the worship of a pagan goddess.

• 1310: The Council of Trier associates witches with the Goddess Diana.

• 1313: Giovanni de Matociis writes in his Historiae Imperiales that many lay people believe in a nocturnal society headed by a queen called Diana.

• 1390: A woman tried by the Milanese Inquisition for belonging to the Society of Diana confesses to worshipping the Goddess of Night and states Diana bestowed blessings upon her.

• 1457: Three women tried in Bressanone confess they belong to the “Society of Diana” (as recorded by Nicholas of Cusa).

• 1508: Italian Inquisitor Bernardo Rategno writes in his Tracatus de Stigibus that a rapid expansion of the witch wult had begun 150 years earlier. He draws this conclusion from his study of trial transcripts from the Archives of the Inquisition at Como, Italy.

• 1519: The Italian poet Girolamo Folengo associates a “Mistress” known as Gulfora with witches who gather to worship at Her Court, in his Maccaronea.

• 1526: Judge Paulus Grillandus writes of witches in the town of Benevento, who worship a goddess at the site of an old walnut tree.

• 1585: Alexander Montgomerie (1550?–1598), Scottish Jacobean courtier and poet, mentions the Nicneven or Nicnevin or Nicnevan (whose name is from a Scottish Gaelic surname, Neachneohain meaning “daughter(s) of the divine”). She is the Scottish version of Diana or Hecate, Dame Habond, Perchta, Herodiana, and Queen of the Fairies. Montgomerie mentions her in his Flyting (c. 1585) and the name was seemingly taken from a woman in Scotland condemned to death for witchcraft before being burnt at the stake as a witch.

• 1576: Bartolo Spina writes in his Quaestrico de Strigibus, listing information gathered from confessions, that “witches” gather at night to worship “Diana,” and have dealings with night spirits.

• 1647: Peter Pipernus writes in his De Nuce Maga Beneventana & De Effectibus Magicis, of a woman named Violanta who confessed to worshipping Diana at the site of an old walnut tree in the town of Benevento.

• 1749: Girolamo Tartarotti associates the Witch Cult with the ancient cult of Diana, in his book Del Congresso Nottorno Delle Lammie.

• 1894: Lady Vere de Vere, after investigating witchcraft as it then existed in the Italian Tyrol region, wrote an article in La Rivista of Rome (June 1894) stating that “… the community of Italian witches is regulated by laws, traditions, and customs of the most secret kind, possessing special recipes for sorcery.”

• 1895: Professor Milani (Etruscan Scholar & Director of Archaeological Museum in Florence) states that various elements of ancient Etruscan occultism have been “marvellously preserved” in the “Italian Witch Tradition.” Professor Milani was familiar with the works of both Lady Vere de Vere and Charles Godfrey Leland. ■

You may also like to read:

Orcus in astrology – The meaning of this binary Plutino in a horoscope

Witch bottles were and are used for protection when other means fail

The witches of Benevento and their secret walnut tree | Stregheria – steghe

Walpurgis Night

Jack o lantern

The Banshee

Black Cat Superstitions

An Authenticated Vampire Story

Mysteries of the Ancient Oaks

The Imp or Witche’s familiar

The Witche’s Ointment

Spirit beings in european folklore

“Witch informant” Maddalena

“Witch informant” Maddalena