Spirit Beings in European Folklore

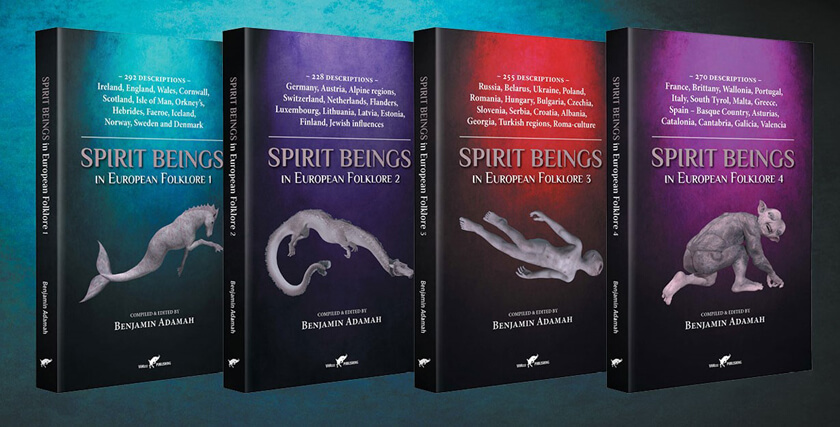

Spirit Beings in European folklore by Benjamin Adamah is a series of 4 compendiums that catalogs 1045 creatures of Europe’s supernatural history. This book-series is made available September 3, 2022 by VAMzzz Publishing. Netflix-series like The Witcher, the Polish production Cracow Monsters or movies on folkloric beings like Border (Swedish: Gräns) about Trolls, The Invisible Guardian-Trilogy (featuring creatures from Basque folklore) and the folkloric horror movie Huldra, feature all kinds of supernatural creatures. When these series trigger your curiosity about the real folkloric background of these spirit beings, this book-series, could be your ideal reading stuff for the coming Autumn and Winter months. No less than 1045 creatures (!) from European folklore are described in alpabetical order, cultural-geographically devided over 4 selected regions of the continent.

Spirit Beings in European Folklore by Benjamin Adamah is the first modern indexation of supernatural folkloric beings that covers the entire European continent. A huge amount of folkloric data fragments were edited into new, more complete, texts, after translating the material from German, Spanish, Portuguese, Basque, Polish, Russian, French, Czech, Lithuanian, Latvian, Estonian, Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian, Romanian, Hungarian and other sources.

Saving spirit beings in our cultural legacy from monoculture

In times where everything seems to push us towards a worldwide monoculture, we were pleased to notice that simultaneously more and more initiatives are taken to preserve the uniqueness and colors of our different cultures. Culture consists for a major part of stories, legends and festivities and habits related to these stories, which we can summarize as “folklore”. And everywhere in Europe (and the rest of the world) spirit beings are a substantial part of the local folklore.

In the province of Valencia they started to dig up the old stories about local supernatural creatures and educate children, for fear this cultural legacy would otherwise disappear forever in a few decades. An interesting initiative has just been launched by the Swedish actress Anna-Maria Wiktorsson who started a youtube series called Misty Folklore about Swedish/Nordic spirit beings. In Eastern Europe and the Baltic states especially a renewed interest in folklore is booming.

Even higher authorities take folklore serious. The Tarasque of Tarascon, a strange amphibious creature, was included in the Inventaire du patrimoine culturel immatériel en France (Inventory of intangible cultural heritage in France) in 2019. Since November 25, 2005, the Tarasque festivals in Tarascon had already been declared by UNESCO as part of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity.

Why Spirit Beings in European Folklore 1,2,3 and 4 instead of one book?

One of the most interesting thing about creating this encyclopedic series was the discovery that – although there are quite a few spirits that are typical of specific geographic locations – many spirits, known by different names, are essentially the same entities, with often the same folkloric rituals associated with them. Many creatures who seem to belong to a certain species however also differ in behavior and appearence, dependent in what country or region they are found and these differences can be quit substantial.

Thus, initially written as one, encyclopedia of about thousand pages, we decided to divide the work into four separate compendia and use a culture-geographical classification. Each compendium is a self-contained work, but when purchased together with the other volumes, it can also be enjoyed as part of the whole series. Below we summarize the contents of the 4 compendiums and this information will account for our choice of 4 European regions.

Spirit Beings in European Folklore 1

Ireland, England, Wales, Cornwall, Scotland, the Isle of Man, the Orkney’s, Hebrides, Faeroe, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Denmark

Compendium-1 deals with the western and northern parts of the continent where Celtic and Anglo-Saxon cultures meet the Nordic. The book catalogs the mysterious beings of Ireland, England, Wales, Cornwall, Scotland, the Isle of Man, the Orkney’s, Hebrides, Faeroe, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Denmark. For centuries the peoples of these regions have mingled and influenced each other in many aspects, including mythology and folklore; the latter perhaps most uniquely expressed in the many varieties of Brook-horses or Water-horses. These half-aquatic phantom creatures are only found – in many varieties – in the English or Gaelic speaking parts of Europe and in Scandinavia. Many other ghostly entities are only found in specific areas or countries, sometimes even becoming cultural icons, like the Irish Leprechaun, the Knockers of Wales, the Scandinavian Trolls and Huldras or the Icelandic Huldufólk. England has its Brownies, many types of Fairies and locally famous Phantom Dogs. Iceland and Scandinavia seem “specialized” in spirit beings that appear fully materialized, like the many types of Illveli (Evil whales) and Draugr, the returning dead.

Compendium-1 describes a fascinating variety of 292 Nordic and Celtic spirit beings in alphabetically arranged paragraphs; accurate with many alternative names for the creatures and subdivisions of related beings.

Spirit Beings in European Folklore 2

Germany, Austria, German speaking Polish and Alpine regions, Luxembourg, Netherlands and Flanders, Luxembourg, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, Ashkenazi / Jewish influences

Compendium-2 deals with the Germanic parts of Central Europe, the Low Countries, the Baltic region and Finland. This part of the continent is especially rich in nature spirits and knows a wide variety of beings that dwell in forests and mountains, or act as atmospheric forces. Dominant are also the many field spirits, the Alp (Nightmare) and variations on Alp-type creatures. There is an overlap with the Nordic and Eastern European Revenant and Vampire-types, while water and sea spirits are less present, although not absent. Among the German speaking peoples field spirits were an integral part of agriculture, with rites that continued into the early 20th century. The same is true for the Baltic states. Forest spirits were also prominent in folklore. Germany has its Moosweiblein and Wilder Mann (Woodwose), the Baltic region has its Mātes, Forest Mothers and Fathers and Finland its Metsän Väki. Then there are ghostly animals and earth and household spirits, like the many types of Kobolds, the Dutch Kabouter and the Kaukas of Prussia and Latvia. The Jews are part of European culture for two millennia. Forced to leave Spain in the 12th century they became the Ashkenazi of Germany, Eastern and Baltic Europe and some of their demons traveled with them, or – like the Dybbuk – were ‘born’ in their new settlements. In our times some of these have become very popular in occult circles and among film makers. They are included in alphabetical order in a special section.

Compendium 2 of Spirit Beings in European Folklore discusses 228 spirit beings in detail, collected mainly from the folklore of German speaking Europe and Baltic and Finnish sources, including their alternative names, with additional references to related or subordinate beings.

Spirit Beings in European Folklore 3

Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Poland, Kashubia, former Prussia, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechia, Slovenia, Serbia, Croatia, Carpathia, Albania, Georgia, Tartar and Turkish regions, Roma-culture

Compendium-3 offers an overview of the mysterious, sometimes beautiful and often gruesome and dark entities of the Slavic countries, the Balkan, Albania, the Roma peoples, the southwestern former Soviet-states and Turkish regions. Many kinds of Vampires or vampiric Revenants are included – purified from popular but erroneous occult fantasies. the undead are prominent in the folklore of Eastern European countries, Albania and parts of Greece and Turkey. Typical are also farm and household spirits like the Domovoy, water spirits and forest demons like the Russian Leshy, the Chuhaister or malicious Polish Bełt, who, like the Ukrainian Blud leads travelers away from the path until they find themselves lost in the deepest part of the forest. Unique is the Russian Bannik or spirit of the bathhouse. Among the Slavs some “demons” originally belonged to the pre-Christian pantheon of Slavic gods and goddesses, like Boginka. It is generally accepted that the Greek figure of the Nymph lies at the base of different beautiful and seductive Slavic spirit beings like the Romanian Iele, the Russian Russalka, the East and South Slavic Vila and the Bulgarian Samodiva. Greek influences entered Slavic culture via the Balkan, while there are also many spirit being that resonate with creatures from Germanic and Northern folklore like the Lisna or Lisnytsia (She of the forest), a kind of Ukrainian version of the Scandinavian Huldra or Skogsrået.

Compendium 3 discusses 255 spirit beings in detail, drawn mainly from Slavic and Turkish folklore, including their alternative names, with additional references to related or subordinate beings.

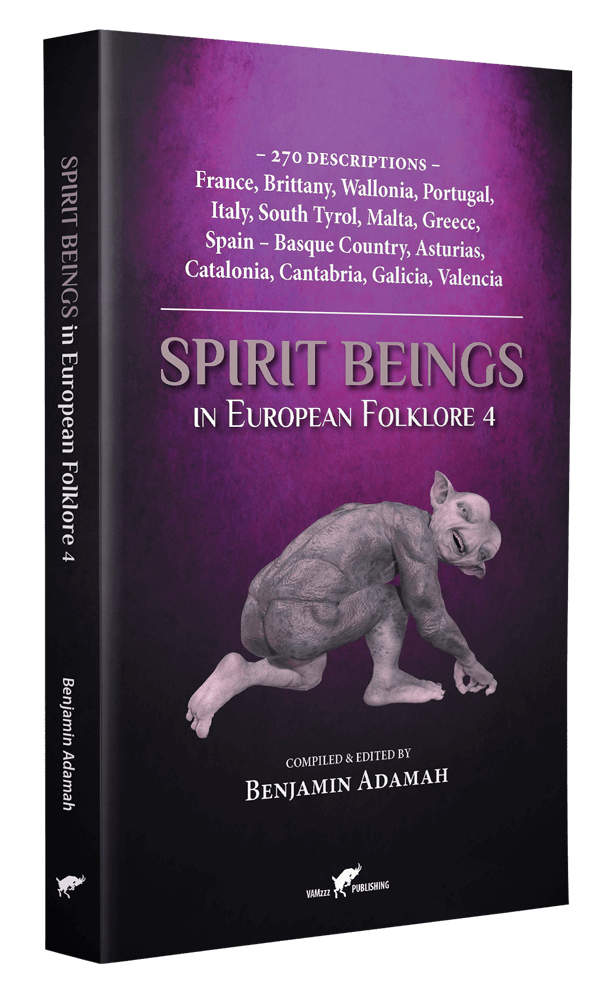

Spirit Beings in European Folklore 4

France, Brittany, Wallonia, Portugal, Italy, South Tyrol, Malta, Greece, Spain – Basque Country, Asturias, Catalonia, Cantabria, Galicia, Valencia

Compendium-4 covers an area that starts with Wallonia and continues via France and the Pyrenees through the Iberian Peninsula to Italy and Greece. This results in a very diverse and colorful collection of spirit beings, due to the many included Basque nature spirits or Ireluak, the Spanish Duendes, the Celtic spirits of Brittany, the prankster Italian Folletti and the creatures from Greece. It is interesting to discover how in particular the many types of (Ancient) Greek spirit beings are at the basis of many continental European spirits. Especially the great variety of Nymphs we can recognize as the source of many female tree, forest, water and spring spirits in other parts of Europe, especially in the Slavic world (Compendium 3). But also the Greek Satyrs and Vampires have their descendants while we see the dwarf-like Kobalos for example evolve into the German Kobold, the Welsh Coblynau and French Gobelin (of which “goblin” was derived). Some creatures from Breton folklore are particularly horrific as the hollow eyed Ankou, the werewolf-like Bugul-nôz or the ghostly and Will o’ the Wisp-like Yan-gant-y-tan who roams the night roads with his five lit candles. Most Italian spirits are less gloomy and the Iberian peninsula shows about everything ranging from the ‘Beauty’ to the ‘Beast’. Compendium 4 includes – among others – many types of dwarfish spirits or Goblins (Lutins, Nutons, Folletti, Duendes, Farfadettes, Korrigans, Minairons), several seductive and female spring creatures, Wild Man-varieties (Basajaun, Jentilak) and an extensive part on the Incubus-Succubus.

Compendium 4 of Spirit Beings in European Folklore discusses 270 spirit beings in detail, collected from Romanesque and Mediterranean folkloric sources. The book includes their alternative names, and has additional references to related or subordinate beings.

About the classification of folkloric spirit beings

Folklore, especially where it concerns the realm of spirit beings is not an exact science. It is possible to draw up a grid of classes and species, but it was the great German folklorist Wilhelm Mannhardt, who already in the 19th century observed that many creatures undergo some sort of evolution, especially where they interact with the human world. He pointed out that certain forest spirits can become field spirits as well. Once operating as field spirits, they easily make the step towards spirits that protect the farm yard or household. In the Germanic and Celtic, as well as in the Baltic, Scandinavian and Slavic regions of Europe, many creatures that act as barn, farm yard or stable spirits remain half wild and maintain a dual nature; they reward people under certain conditions (good behavior, respect, rituals, food offerings etc.) and becoming a nuisance or pest, or even life-threatening when their rules are violated. Although in many cases they simply leave, taking their gift of prosperity with them. There are more “fixed” versions of household spirits, like the ones related to the hearth for example, with roots most likely going back to the Lares and Penates or Roman times.

Many spirits fall under general blanket-terms like Fairies, Goblins (prank pulling dwarf-like creatures), Gnomes, Trolls, water-spirits, Mermaids, Vampiric Revenants, phantoms of dead children (like the Myling), Elves, field spirits, household spirits, weather spirits, changelings, Nymph-like creatures, etc. Most of these spirits cannot be categorized into one single class, but fall in two or sometimes three or more different categories. Although an arbitrary indexation, one could state that roughly the following “classes” are the most notable:

• Alp or Mare-type spirits

• Aquatic Nymphs and Nymphs-like spirits

• Aufhocker-type spirits

• Banshee and Dames Blanches type spirits

• Basque Ireluak

• Bogeys

• Changeling-type spirits

• Dangerous water spirits

• Evil spirits of the dead

• Evil nocturnal spirits

• Female vampiric beings

• Field spirits

• Forest spirits

• Grim-like phantom dogs or creatures

• Hags or hideous Crone-type child luring spirits

• Household spirits

• Icelandic spirits

• Incubus-Succubus type spirits

• Kobolds or dwarfish humanoid looking spirits

• Local spirits

• Midday women

• Mountain spirits

• Neutral or friendly water-spirits

• Prankster spirits

• Sea spirits

• Shape-shifters

• Spirits evolved out of spirits of dead children

• Spirits born from a rooster-egg

• Spirits rooted in Greek-Etruscan-Roman culture

• Spirits rooted in Turkish-Mongolian culture

• Spirits rooted in Jewish culture

• Spirits that are derivatives of ancient pagan gods

• Tree spirits

• Vampiric beings or Revenants

• Weather and wind-spirits

• Were-animals, like Werewolves

• Wild Men and Wild Women

• Wilderness demons leading people astray

• Will-o’-the-wisps

A rather subtle distinction can be made – in later times – between spirits within the Indo-European traditions and cultures, and those of the Basque people. The Basques know a folklore of many kinds and types of Iruliak (pl.) or Genii, who in most cases are all in the dual position of being both a unique or local entity and a manifestation of one of the gods or goddesses, and in most cases this concerns the goddess Mari – regardless of whether the Irelu (sing.) is masculine, like a bull or billy goat.

About the illustrations in Spirit Beings of European Folklore

We have done our best to include some of the more rare and interesting illustrations depicting folkloric beings. Most of them date back to the 19th century or early 20th century. We also added a new set of illustrations (ink drawings) adapted to the classic style to preserve the romantic nature of this theme.

The abbe Richard, in a churchyard, is startled by a huge flame-like Will-o’-the-wisp or Feu Follet on July 2, 1750 (Compendium 1)

The Slavic water demoness Topielica returning to her murderer’s house by Benjamin Adamah (compendium 3)