The snake gods and the human serpent

Snake gods and snake goddesses are common among the most ancient gods of the world. Also common are legends of encounters with snake-like creatures in folklore, like Melusine. Since the beginning of the world the serpent has been regarded as the most mystic of reptiles. He was called “more subtil than any beast of the field,” from the day on which he spoke to Eve and said that if she ate of the fruit of the Tree of Life, her eyes should be opened and she should surely not die, and he has been endowed with human powers again and again, worshipped as a god in every part of the world and depicted in ancient art as possessed of human form and attributes. In Aztec paintings the mother of the human race is always represented in conversation with a serpent who is erect. This is the serpent, “who once spoke with a human voice.”

adopted for blog from Human animals – Peter Hamel

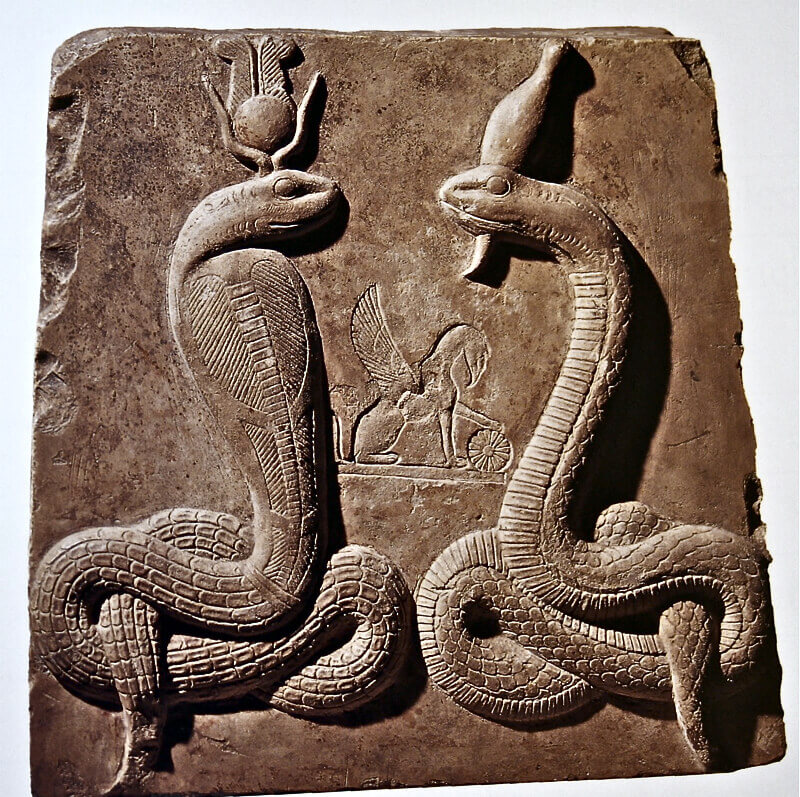

Snake gods are known all over the planet.

Mythology has numberless legends which tell of human or semi-human serpents. The ancient kings of Thebes and Delphi claimed kingship with the snake, and Cadmus and his wife Harmonia, quitting Thebes, went to reign over a tribe of Eel-men in Illyria and became transformed into snakes, just as now Kaffir kings are said to turn into boa-constrictors or other deadly serpents, and some other African tribes believe that their dead chiefs become crocodiles.

Cecrops

Cecrops, the first king of Athens, was supposed to have been half-serpent and half-man, and Cychreus, after slaying a snake which ravaged the island of Salamis, appeared in the form of his victim.

Erechthonios the Serpent-god

When Minerva contended with Neptune for the city of Athens, she created the olive which became sacred to her, and she planted it on the Acropolis and placed it in the charge of the serpent-god, Erechthonios, who is represented as half-serpent, half-man, the lower extremities being serpentine.

A snake as the father of Alexander the Great

The story of Alexander’s birth, as told by Plutarch, is one of the most curious of the man-serpent traditions. Olympias, his mother, kept tame snakes in the house and one of them was said to have been found in her bed, and was thought to be the real father of Alexander the Great. Lucian adopts this view of Alexander’s parentage.

Other snake-gods

The worship of serpent-gods is found amongst many nations. The Chinese god Foki, for instance, is said to have had the form of a man, terminating in the tail of a snake. The same belief in serpent-gods exists among the primitive Turanian tribes. The Accadians made the serpent one of the principal attributes, and one of the forms of Hea, and we find a very important allusion to a mythological serpent in the words from an Accadian dithyrambus uttered by a god, perhaps by Hea:—

Like the enormous serpent with seven heads, the weapon with seven heads I hold it.

Like the serpent which beats the waves of the sea attacking the enemy in front,

Devastator in the shock of battle, extending his power over heaven and earth, the weapon with (seven) heads (I hold it).

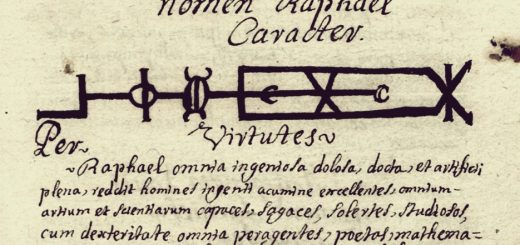

Isis as Agathe Tyche and Osiris as Agathos Daimon in serpent form

Krishna

The story of Krishna is very similar to that of Hercules in Grecian mythology, the serpent forming a prominent feature in both. Krishna conquers a dragon, into which the Assoor Aghe had transformed himself to swallow him up. He defeats also Kalli Naga (the black or evil spirit with a thousand heads) who, placing himself in the bed of the river Jumna, poisoned the stream, so that all the companions of Krishna and his cattle, who tasted of it, perished. He overcame Kalli Naga, without arms, and in the form of a child. The serpent twisted himself about the body of Krishna, but the god tore off his heads, one after the other, and trampled them under his feet. Before he had completely destroyed Kalli Naga, the wife and children of the monster (serpents also) came and besought him to release their relative.

Krishna took pity on them, and releasing Kalli Naga, said to him, “Begone quickly into the abyss: this place is not proper for thee since I have engaged with thee, thy name shall remain through all the period of time and devatars and men shall henceforth remember thee without dismay.” So the serpent with his wife and children went into the abyss, and the water which had been affected by his poison became pure and wholesome. Krishna also destroyed the serpent-king of Egypt and his army of snakes.

Vishnu seated on a throne of snakes

The Lamia

Lamia was an evil spirit having the semblance of a serpent, with the head, or at least the mouth, of a beautiful woman, whose whole figure the demon assumed for the purpose of securing the love of some man whom, it was supposed, she desired to tear to pieces and devour. Lycius is said to have fallen in love with one of these spirits, but was delivered by his master, Apollonius, who, “by some probable conjectures,” found her out to be a serpent, a lamia. Basque mythology and folk lore also describe creatures called Lamia, who are however different from the Greek version.

Melusine’s secret discovered.

Melusina or Melusine

Keats made use of this idea in his poem, “Lamia.” Later the word was used to mean a witch or enchantress. Melusina was another beautiful serpent-woman who disappeared from her husband’s presence every Saturday, and turned into a human fish or serpent.

A modern version of the legend of Melusina is found in Wales. To assume the shape of a snake, witches prepared special charms, and sometimes a ban was placed upon enemies by which they turned into snakes for a time.

A young farmer in Anglesea went to South Wales and there he met a handsome girl whose eyes were “sometimes blue, sometimes grey, and sometimes like emeralds,” but they always sparkled and glittered. He fell in love with her at first sight, and she agreed to become his wife[Pg 176] if he would allow her to disappear twice a year for a fortnight without questioning her as to where she went. To this arrangement the young husband agreed.

For some years he did not trouble himself about his wife’s absence, but his mother began nagging at him, saying that he ought to find out where she went and what she did. Taking his mother’s advice, he disguised himself and followed his wife to a lonely part of a forest not far from their home. Hiding himself behind a huge rock, he noticed from this point of vantage that his wife took off her girdle and threw it down in the deep grass near a dark pool.

Then she vanished, and the next moment he saw a large and handsome snake glide through the grass, just where she had been standing. He chased the reptile, but the snake disappeared into a hole near the pool. The husband went home and waited patiently for his wife’s return, and when she came, he requested her to tell him where she had been. This she refused to do, and when he asked her what she did with her girdle, she blushed painfully.

The next time when she was intending to go away, he seized and hid the girdle, and thus deferred her departure. She was taken ill, and he, hoping to rid her of a baneful charm, threw the girdle in the fire. Then his wife writhed in agony, and when the girdle was burnt up she died. The neighbours called her the Snake-Woman of the South on account of this strange story of her doings.

Melusine in the bathtub

The shoemaker and the Vampire snake-widow

Lamia by John William Waterhouse – 1909

A shoemaker in the Vale of Taff married a widow for her money and, as love seemed lacking on both sides, it was not long before serious quarrels occurred between the couple. Although it was said that hard blows were struck on both sides, the neighbours remarked that it was strange the shoemaker’s wife appeared amongst them without a trace of a bruise on her person. At night loud cries and deep groans arose from the shoemaker’s dwelling, and a certain gentleman of an inquisitive turn of mind decided to discover what took place and hid himself in a loft over the kitchen, to spy on the couple.

Whatever he may have learnt during the proceedings, he said nothing, and a report was spread that he had been “paid to hold his tongue and not divulge the family secret.” At last, however, his discretion failed him, and anger against the shoemaker, with whom he fell into a dispute, made him reveal what he knew. He said that as soon as angry words passed between husband and wife, the latter “assumed from the shoulders upwards, the shape of a snake, and deliberately and maliciously sucked her partner’s blood and pierced him with her venomous fangs.”

No marks were found on the husband’s body, but he grew ever thinner and weaker, and after ailing for many months he died. The doctor who tended him in his last illness declared that he had died from the poisonous sting of a serpent. After this verdict the spy was given the credit of his story, which, however, had a gruesome sequel. He and the doctor were found lying helpless in the churchyard one morning.

When roused from what seemed a fatal slumber, they said they had been invited by the shoemaker’s widow to drink with her in memory of her late dear second husband. Then she sprang upon them in the shape of a snake and stung them severely. They had only strength enough left to crawl to the churchyard, where they would probably have died from torpor had not the neighbours roused them. The widow was never seen again, but a snake constantly appeared in the neighbourhood and could not be killed by any means, so that it earned the name of “the old snake-woman.”

Elsie Venner

Oliver Wendell Holmes, who was interested in the subject of prenatal influences, depicted the heroine of his well-known novel, “Elsie Venner,” as a girl who had received the taint of a serpent before birth, from a snakebite suffered by her mother.

Elsie’s friend, Helen Darley, knew the secret of the fascination which looked out of the cold, glittering eyes. She knew the significance of the strange repulsion which she felt in her own intimate consciousness underlying the inexplicable attraction which drew her towards the young girl in spite of her repugnance.

When Elsie was taken ill her doctor said that she had lived a double being, as it were, the consequence of the blight which fell upon her in the dim period before consciousness.

“Elsie Venner” is an American story, but India, where the snake is even more familiar, is the home of many human-serpent stories, and legends of serpent descent.

Veve of the creator voodoo-god Dhambalah

This is my lineage! I am a Nagbansi

Near Jait in the Mathura district is a tank with the broken statue of a hooded serpent on it. Once upon a time a Raja married a princess from a distant country and, after a short stay there, decided to take his wife home, but she refused to go until he had declared his lineage. The Raja told her she would regret her curiosity, but she persisted. Finally he took her to the river and there warned her again. She would not take heed and he entreated her not to be alarmed at whatever she saw, adding that if she did she would lose him.

Saying this, he began slowly to descend into the water, all the time trying to dissuade her from her purpose, till it became too late and the water rose to his neck. Then, after a last attempt to induce her to give up her curiosity, he dived and reappeared in the form of a Naga (serpent). Raising his hood over the water he said, “This is my lineage! I am a Nagbansi.”

His wife could not suppress an exclamation of grief, on which the Naga was turned into stone, where he lies to this day.

The daughter of the serpent-king

A member of the family of Buddha fell in love with the daughter of a serpent-king. He was married to her and presently became the sovereign of the country. His wife had obtained possession of a human body, but a nine-headed snake occasionally appeared at the back of her neck. While she slept one night her husband chopped the serpent in two at a single blow, and this caused her to become blind.

A Buddha priest who had become a serpent

Another curious legend is told of a Buddha priest who had become a serpent because he had killed the tree Elapatra, and he then resided in a beautiful lake near Taxila. In the days of Hiuen-Tsiang, when the people of the country wanted fine weather or rain they went to the spring accompanied by a priest, and, “snapping their fingers, invoked the serpent,” and immediately obtained their wishes.

The snake tribe in the Punjaub

The snake tribe is common enough in the Punjaub. Snake families go through many ceremonies, saying that in olden days the serpent was a great king. If they find a dead snake they put clothes on it and give it a regular funeral. The snake changes its form every hundred years, when it becomes either a man or a bull. Snake-charmers have the power of recognising these transformed snakes, and follow them stealthily until they return to their holes and then ask them where treasure is hidden. This they will do on consideration of a drop of blood from the little finger of a first-born son.

Dhambalah depicted in a work of art

Snake-skin

Among fairy tales the favourite story is that of a human being who dons a snake-skin, and when it is burnt he resumes human form. The snake-bridegroom is an exceedingly popular version of this idea.

There was once a poor woman, who had never borne a child and she prayed to God that she might be blessed with one, even though she were to bring forth a snake. And God heard her prayer, and in due course she gave birth to a snake. Directly the reptile saw the light of day it slipped down from her lap into the grass and disappeared. Now the poor woman mourned constantly for the snake, because after God had heard and granted her prayer, it grieved her that the being whom she had conceived should have vanished without leaving a trace as to its whereabouts. Twenty years passed, and then the snake returned and said to its mother, “I am the serpent to which you gave birth, and which fled from you into the grass, and I have come back, mother, so that you may demand the king’s daughter for me in marriage.”

At first the mother rejoiced at the sight of her son, but soon she grew mournful because she did not know how she dare to demand the hand of the king’s daughter for a serpent, especially as she was very poor. But the serpent said, “Go along, mother, and do what I ask; even if the king won’t give his daughter, he can’t cut your head off for the mere asking. But whatever he says to you do not look back until you get home again.”

The mother allowed herself to be persuaded and went to the king. At first the servants would not let her into the palace, but she went on asking until they admitted her. When she entered the king’s presence she said to him, “Most gracious Majesty, there is your sword and here is my head. Strike if you must, but let me tell you first that for a long time I was childless and then I prayed to God to bless me, even though I were to bring forth a serpent, and He blessed me and I brought forth a serpent. As soon as it saw the light it vanished into the grass and after twenty years it has returned to me and has sent me here to ask for the hand of your daughter in marriage.”

The king burst into laughter and said, “I will give my daughter to your son if he builds me a bridge of pearls and precious stones from my palace to his house.”

Then the mother turned to go home, and never looked back, and when she left the palace a bridge of pearls and diamonds arose all the way behind her till she reached her own house. When the mother told the serpent what the king had said, the serpent remarked to her, “Go again and see whether the king will give me his daughter, but whatever he answers don’t look round as you come back.”

This time the king told the mother that if her son could give his daughter a better palace than his own, he should have her for a wife. The mother went back without looking behind her, and found that her house had changed into a palace, and everything in it was three times as good as in the king’s palace. All the furniture was made of pure gold.

Then the serpent asked his mother to go back to the palace and fetch the king’s daughter, and this time the king told the princess she must marry the serpent. There was a splendid wedding, and in due course the young wife found she was to become a mother. Then her friends grew inquisitive, saying, “If you are living with a serpent how can you hope to have a child?” At first she would not answer, but when her mother-in-law insisted on putting the same question, she replied, “Mother, your son is not really a serpent, but a young man, so handsome that there is none other like him. Every evening he strips off his snake-skin and in the morning he enters it again.”

When the serpent’s mother heard this she rejoiced greatly, and longed to see her son after he had stripped off his snake-skin.

Presently the two conspirators arranged that when the young man had gone to bed, they should burn the discarded skin, and while his mother put it in the oven, his wife was to pour cold water on her husband lest he should be destroyed by the heat. No sooner had he laid himself down to sleep, than they carried out their plan, but the smell of the burning skin made him cry out, “What have you done? May God punish you. Where can I go in the condition I now am?” But the women comforted him and said it was better for him to live among ordinary mortals than in the snake form, and before long the king resigned his throne in his favour, and all turned out happily.

The queen who gave birth to a serpent

A very similar story is told of a queen who also gives birth to a serpent. She is allowed to nurse and fondle her offspring in the usual fashion, but for twenty-two years it does not speak and its first utterance is to demand from its parents a wife.

When the parents remark that no nice girl would care to marry a serpent, he tells them not to look in too high a class for a mate.

In this case the father does the wooing, but the mother evokes the truth about her son. When she learns about the snake-skin, she makes the young wife help to burn it, and tragedy results. The husband curses his wife, saying that she will not see him again until she has worn through iron shoes, and that she shall not give birth to her child until he embraces her once more by putting his right arm round her.

Then he vanishes for three years, and all that time she is unable to bear her child, so she decides to seek her husband. She travels through the world and comes to the house of the Sun’s mother, and when the Sun comes indoors she inquires whether he has seen her husband. But the Sun can do nothing for her but to send her to the Moon. The same disappointment awaits her there, and the Moon sends her to the Winds. After many striking adventures she finds her husband, makes him undo his curse, and gives birth to a son who has golden locks and golden hands.

Serpent-marriage

In another story of serpent-marriage a woman stands in doubt because she cannot cross a river. A serpent comes out of the river and says, “What will you give me if I carry you across?” The woman, having no other possessions, promises to give her coming child; if it is a girl as a wife, if a boy as a “name friend.” In after years she has to fulfil her promise and, taking her daughter to the bank of the river, she sees the snake draw her beneath the water. In the course of time the girl bears her husband four snake sons.

Ainu snake-baby

An Ainu girl gave birth to a snake as the result of the sun’s rays shining on her while she slept, and the snake turned into a child.

Melusine in bathtub in German manuscript

The Cobra-legend of the Dyaks and Silakans

The Dyaks and Silakans will not kill the cobra because in remote ages a female ancestor brought forth twins, a boy and a cobra. The cobra went to the forest, but told the mother to warn her children that if they were ever bitten by cobras they must stay in the same place for a whole day and that then the venom would take no effect. The boy then met his cobra brother in the jungle one day and cut off his tail, so that now all cobras have a blunted tail.

Snake into human transformation

In folk-tales the serpent frequently mates with a woman. A curious Basuto story concerns a girl called Senkepeng, who was deserted by her friends and taken home by an old woman, who said she would make a nice wife for her son. Her son turned out to be a serpent, whom no one had ever seen outside his hut, but he had married all the girls of the tribe in succession with fatal results to them, because he ate all the food.

Every morning the girl was awakened by a blow of the serpent’s tail and was then ordered to go and prepare his food. At last she grew tired of this treatment and resolved to run away. Her serpent-husband pursued her, but she sang a charm or incantation and this delayed his progress and gave her a chance of continuing her flight. Whenever the serpent came up to her she repeated her song.

At last she reached her father’s village and told her story, and people were ready to defend her against her pursuer. As soon as the serpent came in sight Senkepeng sang her charm, and the people attacked the serpent and slew it. Presently the serpent’s mother arrived and burnt the mutilated corpse, wrapping the ashes in a skin which she threw into a pond. Walking three times round the pond, without speaking a word, she caused her son to come to life again, and he came out of the pond as a human being, and Senkepeng welcomed him as her husband. In another variant the serpent’s ashes are put in a vase of clay, which is given to Senkepeng. Afterwards she uncovers the vase and a man steps out from it.

Little men-serpents

The first Dindje Indian had two wives, one of whom would have nothing to say to him. She used to disappear during the day, and he followed her to find out her secret. He saw her go into a marsh where she met a serpent. When she returned to the hut she had several children, but hid them from her husband under a cover. The man discovered the hiding-place, and there found horrible little men-serpents, which he killed. Thereupon the woman left him and he never saw her again.

Serpent-kidnappers

In a Bengal story a mighty serpent, after slaughtering a whole family except one beautiful daughter, carries her off to his watery tank, from which she is rescued by a prince. In Russia it is believed that mortal maidens are carried off by serpents.

Snake goddess from ancient Crete.

Hairs turning into snakes

The Indians are very superstitious. Otto Stoll, author of “Suggestion und Hypnotismus,” showed a friendly Cakchiquel Indian one of his hairs under the microscope. The Indian asked to have it back that he might preserve it, saying that if it were lost, it would turn into a snake, and he would then have to suffer great trouble through snakes all his life. When Dr. Stoll appeared to be sceptical, he told him that he had often seen the long hairs which native women combed out and let fall into the river, become transformed into serpents as they fell. This is a widespread belief, and in an early Mexican dictionary by Molina, in 1571, the word “tzoncoatl” is translated, “the snake which is formed out of horse’s hair which fell into the water.”

White snake maiden

The white snake especially may sometimes be a lovely transformed maiden, as appears from the story of a cowboy who makes a friend of a white snake which comes to play with him and twines about his legs. One evening in midsummer he beholds a fair maiden, who says she is the daughter of an Eastern king and has been forced to spend her life through enchantment in the form of a white snake, with permission to resume human shape on midsummer night every quarter of a century.

The cowboy is the first human being who has not shrunk from her when she appears in reptile form. She tells him that she will come again, and will wind herself three times round his body and give him three kisses. If he should shrink from her then she will have to remain a snake for ever. When she appears, the youth stands firm while the reptile caresses him and, lo and behold, there is a crash and a flash and he finds himself in a magnificent palace, with a beautiful girl beside him who becomes his wife.

Bathing girls in Russia

The Russians have a story of some girls bathing, when a snake comes out of the water and sits upon the clothes of the prettiest one, saying he will not move till she promises to marry him. She agrees, and that very night an army of snakes seize her and carry her beneath the water, where they become men and women. She stays for some years with her husband, and is then allowed to go home and visit her mother. The latter, discovering the husband’s name, goes to the water and calls upon him. When he comes to the surface she chops off his head with an axe. Probably the snake-bride has been told by her husband not to mention his name for fear of his death, the name being taboo.

Zuni legend of serpent-child

In a Zuni legend the daughter of a chief bathes in a pool sacred to Kolowissa, the serpent of the sea. Kolowissa in anger appears to the maiden in the form of a child, whom she takes to her home. There the child changes into an enormous serpent, who induces her to go away with him, and when she does so he transforms himself again into a handsome youth.

Incredulous that such happiness can befall her, she expresses her doubts to the young man, but he then shows her his shrivelled snake-skin as proof that he is the god of the waters and that he loves her well enough to make her his wife.

Snake magic

A beautiful girl in New Guinea was beloved by a chief of a strange tribe, and he was so fearful of entering her father’s territory that he asked a sorcerer for a charm which would enable him to change into a snake the moment he crossed the boundary of his own country. In this form he entered the girl’s hut, and on seeing the reptile she began to scream. Her father, however, was more astute and saw the serpent was really a man, so he bade his daughter to go to him, as he must be a great chief to be thus able to transform himself.

She obeyed his command, and as the serpent went slowly, her father advised her to burn his tail with a hot banana leaf to make him hurry. This she also did, but at the boundary the snake vanished and presently a handsome young man came up to her and told her he was the serpent, showing certain burns on his feet and legs in proof of the statement.

Hindu snake goddess

The Vouivre

In France the serpent with a jewel in its head is called vouivre, which is the same as our basilisk or dragon. The vouivre is a reptile from a yard to two yards long, having only one eye in its head, which shines like a jewel and is called the carbuncle. This jewel is regarded as of inestimable value, and those who can obtain one of these treasures become enormously rich. Many of the legends deal with the robbery of this jewel from the serpent, a crime which is frequently punishable by death or madness.

St. George and the Dragon

The French have several variants of the story of St. George and the Dragon. At the castle of Vaugrenans, for instance, there lived a lovely lady whose beauty had led her far astray from the path of virtue. She was changed into a basilisk and terrorised the country by her misdeeds. Her son George was a handsome knight, whose natural piety led him to live a life of good deeds. George decided that he must set his country free from the depredations of the monster reptile, which never ceased to prey upon the neighbourhood and he did battle with it as once the archangel, St. Michael, had combated the dragon. George killed the serpent and his horse trampled what remained of it beneath its hoofs.

George was very sad, however, in spite of his victory, and he asked St. Michael, who had witnessed the struggle, what was the punishment for one who had slain his own mother.

“He ought to be burnt,” replied St. Michael, “and his ashes strewn to the winds.”

So George had to suffer the penalty of being burnt and his ashes were scattered to the winds. So far the story bears a marked resemblance to the family story of the Lambton worm, but the French tale has a curious sequel. The ashes fell in one heap instead of scattering to the wind, and a young girl who was passing gathered them up. Near by she found an apple of Paradise, which she ate. In due course she gave birth to a son, and when the infant was baptised, it cried in a loud tone of voice, “I am called George and I have been born on this earth for the second time.” Later he was made a saint.

Ronan genius

The Roman genius, which accompanies every man through life as his protector, frequently took the shape of a serpent.

Eating snakes

In many lands, by eating a snake, wisdom is acquired, or the language of animals mastered, and generally a particular snake is mentioned by name. Thus with Arabs and Swahilis it is the king of snakes: among Swedish, Danish, Celtic or Slavonic peoples it is a white snake or the fabulous basilisk with a crown on its head, which resembles the jewel-headed serpent of Eastern lore.

The Naga

In the country of Râma there stood a brick stupa or tower, about a hundred feet high, in the time of Hiuen-Tsiang. The stupa constantly emitted rays of glory, and by the side of it was a Naga tank. The Naga frequently changed his appearance into that of a man, and, as such, encircled the tower in the practice of religion, that is, he turned religiously with his right hand towards the tower.

Possessed by snake spirits

In New Guinea it is believed that a witch is possessed by spirits which can be expelled in the form of snakes. Among the Ainus, madness is explained as possession by snakes. The Zulus believe that an ancestor who wishes to approach a kraal takes serpent shape. In Madagascar different species of snakes are the abode for different classes, one for common people, one for chiefs, and one for women, and in certain parts of Europe it is solemnly believed that people may assume serpent-form during sleep.

Man and Serpent

The fact that the serpent-stories of the nature here collected, are so numerous seems to point to a definite occult connection between the highest living organism, man, who is represented by a vertical line, and the reptile, the serpent, represented by the horizontal line, the two together forming the right angle.

You may also like to read:

Sex and Mediumship – quotations on the observation of ectoplasma

Typhon in astrology and the Fukushima disaster

https://forums.stanwinstonschool.com/discussion/6409/nu-wa-chinese-snake-goddess