Investigating “An authenticated Vampire story” by Franz Hartmann

An authenticated Vampire story by the famous occultist Dr. Franz Hartmann was first published as a true account on vampirism in THE OCCULT REVIEW, London, September 1909 – whose founder and editor was an English engineer by the name of Ralph Shirley. It contains several classic ingredients of the vampire fiction, once started by John William Polidori and Lord Byron, continued by Jean Charles Emmanuel Nodier with his theatre play Le Vampire (1820), Bram Stoker and his Dracula, and up to this day prolonged by so many copycats in books, movies and TV-series. Hartmann’s story contains the lonely castle in the Carpathian Mountains, haunted by apparitions, the portrait of a beautiful but sinister countess, gloomy corridors, a spooky carriage drawn by two black horses and a portrait with living eyes. To good to be true. But the thing is, the newspaper article, Hartmann refers to is real, and the villagers of Bethenykörös, Wallachia, actually did burn down Castle Bethenykörös because they were convinced a vampire “lived” in it, who they blamed for the death of their children…

The original newspaper article – at page 8 in the Neues Wiener Journal of June 10 – 1909, which Franz Hartmann’s “An authenticated Vampire story” was based upon.

We find just a few facts of Hartmann’s story in the original newspaper article, which I have translated below:

Destruction of a castle due to superstition

We receive the news that Bethenykörös Castle has fallen victim to a strange superstition of the Wallachian population of the village of the same name. Bethenykörös is situated in a wildly romantic area on the southeastern slope of the Carpathian Mountains and may once have been a a very strong fortress against the Turks. It has not been inhabited for many years and only one castellan lived with his wife in a side wing. There were a series of stories about the inhabitants of the castle. Among other things, it was generally believed that the last Count Bethenykörös died as a “vampire”. When in the last few weeks numerous peasants’ children died one after the other due to an epidemic, the superstitious people claimed that the count had murdered them, and decided to destroy the tomb of the “vampire”. On this occasion, probably due to carelessness, fire broke out, which destroyed the The state building till only the foundation walls remained. The castle is said to have belonged to a young cavalry officer who lives in Vienna and who acquired it by inheritance. [1]

The story Hartmann published, in which he refers correctly to the contents of the newspaper article, was meant as additional information. The report in the newspaper itself, about Eastern European villagers suspecting a vampire (or revenant) as being the cause of a disease outbreak, waning health or even death, as in this case, is not exeptional. There exists quite a bulk on anekdotes about the vampire-phenomena in Eastern Europe, up to Russia, Greece and Turkey as well as in many German speaking areas in Central Europe. Many accounts were published by Antoine Augustin Calmet, O.S.B. (26 February 1672 – 25 October 1757) in his Dissertations sur les apparitions des anges, des démons et des esprits, et sur les revenants et vampires de Hongrie, de Bohême, de Moravie et de Silésie, Paris : de Bure l’aîné of 1746 (Expanded and republished in 1751).

Wilhelm Mannhardt wrote about vampires in Zeitschrift fur deutsche Mythologie und Sittenkunde – Erster Band – 1853. W. R. S. Ralston, M. A. tapped into the vampire domain in his Russian Fairy Tales – A Choice Collection of Muscovite Folk-lore (1868) and Songs of the Russian People (1872).

In July 1910, Dudley Wright published an essay entitled A Living Vampire in the same The Occult Review wherein Hartmann had published his story a year earlier. A few years later Wright expanded his essay on vampires into this still popular book entitled Vampires and Vampirism. in which he explores the vampire phenomena in different parts of the world and in different times in our history, starting with ancient Babylonia, Assyria and Greece and continuing with the vampire in Great Britain and the British Empire, Germany and it’s surrounding countries, Bavaria, Hungary, Silesia, Bulgaria and Russia.

The Vampire, His Kith and Kin: A Critical Edition, was published by Montague Summers in 1928, followed by The Vampire in Europe: A Critical Edition of 1929. More recent work about the vampire and revenant (the returning dead) was published by Claude Lecouteux in The Return of Dead (1996) and The Secret History of Vampires (1999).

Why Hartmann believed it was Countess Elga, the vampires daughter who caused the trouble

In his story Hartmann writes that he was with a friend of him, who revealed that he had visited the very same castle in 1907 when he was building a nearby road (this friend is believed to be Ralph Shirley-JR). He had seen a portrait hanging in the castle which he described as being particularly evil and animated. The friend was accompanied by two other men, one of whom reported being “visited” by a woman who looked exactly like Countess Elga, the woman in the portrait. It was apparent from the story that it was she who was the vampire, and not her father, whose grave was destroyed by the angry villagers. Hartmann swears as to the truth of the story. His account in The Occult Review showed a photograph of huge painting taken by his friend, the engineer. The painter was the celebrated Austrian portrait painter Hans Makart (1840-1884)– who went mad at the age of 44 shortly after completing the portrait of the Countess.

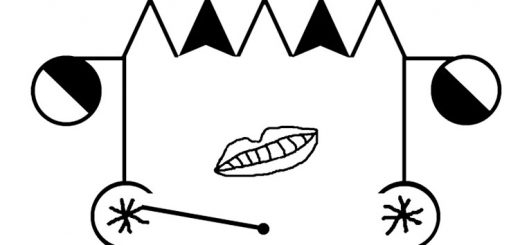

The infamous painting of the vampire Countess Elga (as confirmed during a seance by the Countess herself), painted by the celebrated Autrian painter Hans Makart (1840-1884) who went mad after finishing the canvas in one version of the story.

An authenticated Vampire story – published in The Occult Review, September 1909

On June 10, 1909, there appeared in a prominent Vienna paper (the Neues Wiener Journal) a notice (which I herewith enclose) saying that the castle of B— had been burned by the populace, because there was a great mortality among the peasant children, and it was generally believed that this was due to the invasion of a vampire, supposed to be the last Count B—, who died and acquired that reputation. The castle was situated in a wild and desolate part of the Carpathian Mountains and was formerly a fortification against the Turks. It was not inhabited owing to its being believed to be in the possession of ghosts, only a wing of it was used as a dwelling for the caretaker and his wife.

Now it so happened that when I read the above notice, I was sitting in a coffee-house at Vienna in company with an old friend of mine who is an experienced occultist and editor of a well known journal and who had spent several months in the neighborhood of the castle. From him I obtained the following account and it appears that the vampire in question was probably not the old Count, but his beautiful daughter, the Countess Elga, whose photograph, taken from the original painting, I obtained. My friend said:—

“Two years ago I was living at Hermannstadt, and being engaged in engineering a road through the hills, I often came within the vicinity of the old castle, where I made the acquaintance of the old castellan, or caretaker, and his wife, who occupied a part of the wing of the house, almost separate from the main body of the building. They were a quiet old couple and rather reticent in giving information or expressing an opinion in regard to the strange noises which were often heard at night in the deserted halls, or of the apparitions which the Wallachian peasants claimed to have seen when they loitered in the surroundings after dark. All I could gather was that the old Count was a widower and had a beautiful daughter, who was one day killed by a fall from her horse, and that soon after the old man died in some mysterious manner, and the bodies were buried in a solitary graveyard belonging to a neighboring village. Not long after their death an unusual mortality was noticed among the inhabitants of the village: several children and even some grown people died without any apparent illness; they merely wasted away; and thus a rumor was started that the old Count had become a vampire after his death. There is no doubt that he was not a saint, as he was addicted to drinking, and some shocking tales were in circulation about his conduct and that of his daughter; but whether or not there was any truth in them. I am not in a position to say.

“Afterwards the property came into possession of —, a distant relative of the family, who is a young man and officer in a cavalry regiment at Vienna. It appears that the heir enjoyed his life at the capital and did not trouble himself much about the old castle in the wilderness; he did not even come to look at it, but gave his direction by letter to the old janitor, telling him merely to keep things in order and to attend to repairs, if any were necessary. Thus the castellan was actually master of the house and offered its hospitality to me and my friends.

“One evening myself and my two assistants, Dr. E—, a young lawyer, and Mr. W—, a literary man, went to inspect the premises. First we went to the stables. There were no horses, as they had been sold; but what attracted our special attention was an old queer-fashioned coach with gilded ornaments and bearing the emblems of the family. We then inspected the rooms, passing through some halls and gloomy corridors, such as may be found in any old castle. There was nothing remarkable about the furniture; but in one of the halls there hung in a frame an oil-painting, a portrait, representing a lady with a large hat and wearing a fur coat. We all were involuntarily startled on beholding this picture; not so much on account of the beauty of the lady, but on account of the uncanny expression of her eyes, and Dr. E—, after looking at the picture for a short time, suddenly exclaimed—

” ‘How strange! The picture closes its eyes and opens them again, and now begins to smile!’ .

“Now Dr. E— is a very sensitive person and has more than once had some experience in spiritism, and we made up our minds to form a circle for the purpose of investigating this phenomenon. Accordingly, on the same evening we sat around a table in an adjoining room, forming a magnetic chain with our hands. Soon the table began to move and the name “Elga” was spelled. We asked who this Elga was, and the answer was rapped out ‘The lady, whose picture you have seen.’

” ‘Is the lady living?’ asked Mr. W—. This question was not answered; but instead it was rapped out: ‘If W— desires it, I will appear to him bodily tonight at two o’clock.’ W— consented, and now the table seemed to be endowed with life and manifested a great affection for W—; it rose on two legs and pressed against his breast, as if it intended to embrace him.

“We inquired of the castellan whom the picture represented; but to our surprise he did not know. He said that it was the copy of a picture painted by the celebrated painter Hans Markart of Vienna, and had been bought by the old Count because its demoniacal look pleased him so much.

“We left the castle, and W— retired to his room at an inn, a half-hour’s journey distant from that place. He was of a somewhat skeptical turn of mind, being neither a firm believer in ghosts and apparitions nor ready to deny their possibility. He was not afraid, but anxious to see what would come out of his agreement, and for the purpose of keeping himself awake he sat down and began to write an article for a journal.

“Towards two o’clock he heard steps on the stairs and the door of the hall opened, there was a rustling of a silk dress and the sound of the feet of a lady walking to and fro in the corridor.

“It may be imagined that he was somewhat startled; but taking courage, he said to himself: ‘if this is Elga, let her come in.’ Then the door of his room opened and Elga entered. She was most elegantly dressed and appeared still more youthful and seductive than the picture. There was a lounge on the other side of the table where W— was writing, and there she silently posed herself. She did not speak, but her looks and gestures left no doubt in regard to her desires and intentions.

“Mr. W— resisted the temptation and remained firm. It is not known, whether he did so out of principle or timidity or fear. Be this as it may, he kept on writing, looking from time to time at his visitor and silently wishing that she would leave.

At last, after half an hour, which seemed to him much longer, the lady departed in the same manner in which she came.

“This adventure left W— no peace, and we consequently arranged several sittings at the old castle, where a variety of uncanny phenomena took place. Thus, for instance, once the servant-girl was about to light a fire in the stove, when the door of the apartment opened and Elga stood there. The girl, frightened out of her wits, rushed out of the room, tumbling down the stairs in terror with the petroleum lamp in her hand, which broke and came very near to setting her clothes on fire. Lighted lamps and candles went out when brought near the picture, and many other ‘manifestations’ took place, which it would be tedious to describe; but the following incident ought not to be omitted.

“Mr. W— was at that time desirous of obtaining the position as co-editor of a certain journal, and a few days after the above-narrated adventure he received a letter in which a noble lady of high position offered him her patronage for that purpose. The writer requested him to come to a certain place the same evening, where he would meet a gentleman who would give him further particulars. He went and was met by an unknown stranger, who told him that he was requested by the Countess Elga to invite Mr. W— to a carriage drive and that she would await him at midnight at a certain crossing of two roads, not far from the village. The stranger then suddenly disappeared.

“Now it seems that Mr. W— had some misgivings about the meeting and drive and he hired a policeman as detective to go at midnight to the appointed place, to see what would happen. The policeman went and reported next morning that he had seen nothing but the well-known, old fashioned carriage from the castle with two black horses attached to it standing there as if waiting for somebody, and that he had no occasion to interfere and merely waited until the carriage moved on. When the castellan of the castle was asked, he swore that the carriage had not been out that night, and in fact it could not have been out, as there were no horses to draw it.

… I saw a carriage with gilded ornaments …

“But this is not all, for on the following day I met a friend who is a great skeptic and disbeliever in ghosts and always used to laugh at such things. Now, however, he seemed to be very serious and said: ‘Last night something very strange happened to me. At about one o’clock this morning I returned from a late visit and as I happened to pass the graveyard of the village, I saw a carriage with gilded ornaments standing at the entrance. I wondered about this taking place at such an unusual hour, and being curious to see what would happen, I waited. Two elegantly dressed ladies issued from the carriage. One of these was young and pretty, but threw at me a devilish and scornful look as they both passed by and entered the cemetery. There they were met by a well-dressed man, who saluted the ladies and spoke to the younger one, saying: “Why, Miss Elga! Are you returned so soon?” Such a queer feeling came over me that I abruptly left and hurried home.

“This matter has not been explained; but certain experiments which we subsequently made with the picture of Elga brought out some curious facts.

“To look at the picture for a certain time caused me to feel a very disagreeable sensation in the region of the solar plexus. I began to dislike the portrait and proposed to destroy it. We held a sitting in the adjoining room; the table manifested a great aversion against my presence. It was rapped out that I should leave the circle, and that the picture must not be destroyed. I ordered a Bible to be brought in and read the beginning of the first chapter of St. John, whereupon the above-mentioned Mr. E— (the medium) and another man present claimed that they saw the picture distorting its face. I turned the frame and pricked the back of the picture with my penknife in different places, and Mr. E—, as well as the other man, felt all the pricks, although they had retired to the corridor.

“I made the sign of the pentagram over the picture, and again the two gentlemen claimed that the picture was horribly distorting its face.

“Soon afterwards we were called away and left that country. Of Elga I heard nothing more.”

Thus far goes the account of my friend the editor. There are several points in it which call for an explanation. Perhaps the sages of the S.P.R. will find it by investigating the laws of nature ruling the astral plane, unless they prefer to take the easier route, by proclaiming it all to be humbug and fraud.

Franz Hartmann

Franz Hartmann

Franz Hartmann (22 November 1838, Donauwörth – 7 August 1912, Kempten im Allgäu) was a German-American medical doctor, theosophist, occultist, geomancer, astrologer, and author of many books on occult and esoteric subjects. He translated the Bhagavad Gita into German and was an associate of Helena Blavatsky and Chairman of the Board of Control of the Theosophical Society Adyar. He published the journals Lotusblüthen (1893-1900) and Neue Lotusblüten (1908-1913). His articles on yoga popularized the subject within Germany. Hartmann supported the Guido von List Society (Guido von List Gesellschaft). According to Theodor Reuss he was one of the original founders of the magical order that would later be known as Ordo Templi Orientis, along with Reuss and Carl Kellner.

Note

[1] Zerstörung eines Schlosses aus Aberglauben

Wir erhalten die Nachricht, dass das Schloß Bethenykörös einem seltsamen Aberglauben der wallachischen Bevölkerung des Dorfes gleichen Namens zum Opfer gefallen ist. Bethenykörös liegt in wildromatischer Gegend am Südostabhang des Karpathengebirges und mag einst ein überaus festes Bollwerk gegen die Türken gewesen sein. Seit langen Jahren war es nicht mehr bewohnt und nur ein Kastellan haufte mit seiner Frau in einem Seitenflügel. Ja der Bevölkerung warwar eine Reihe von Geschichten uber die Bewohner des Schlosses verbreitet, unter anderem glaubte man allgemein, der lezte Graf Bethenykörös sei als “Vampir” gestorben. Als nun in den lezten Wochen zahlreiche Bauernkinder infolge einer Seuche rasch nacheinander starben, behauptete das aberglaubige Volk, der Graf habe sie ermordet, und beschloss die Grabstatte des “Vampirs” zu zerstören. Bei dieser Gelegenheit ist wahrscheinlich durch unachtsamkeit Feuer ausgebrochen, dem der Staatliche Bau bis auf die Grundmauern zum Opfer gefallen ist. Das Schloß soll zulezt einem in Wien lebenden jungen Kavallerieoffizier, der es durch Erbschaft erwarm, gehört haben.

You may also like to read:

The real vampire in Russia and Slavonian countries

Historical werewolf cases in Europe

The incubus or succubus – nightmare or astral sex date?