Olympic Spirits – a unique compilation of grimoires

Olympic Spirits have fascinated me over the years as I encountered them in various grimoires, though they were often treated as mere “side dishes” in occult literature. This treatment stands in stark contrast to the remarkable powers attributed to these spirits. One intriguing aspect is the redundancy in evoking the Olympic Spirits, as their qualities and the psychospheres they govern closely resemble those of the seven classical planetary angels, which have clearer and more thoroughly tested rituals. Many practitioners of magic likely share this curiosity, which is why I dedicated the first volume of my series of old German grimoires in translation to exploring these enigmatic entities. These spirits have been a persistent presence in manuscripts from the Western Magickal tradition for at least 500 years, yet their significance has often been overlooked.

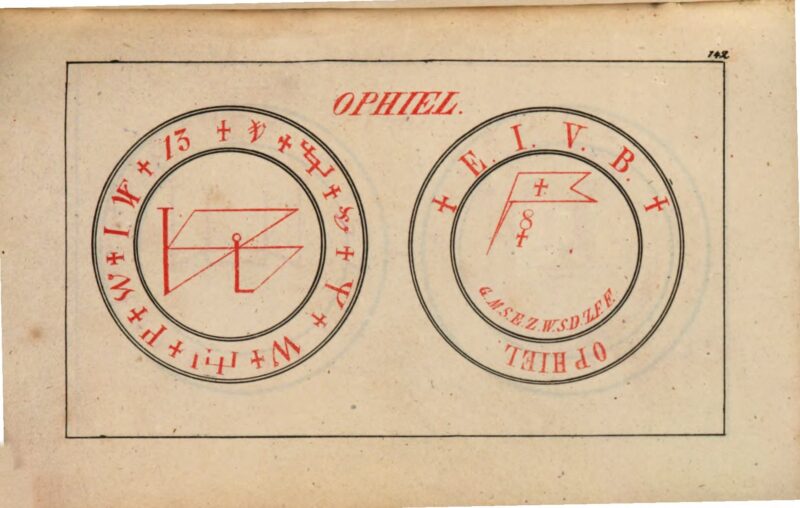

Front and back sigil of Ophiel, the Olympic Spirit attributed to Mercury in an edition of Magia Naturalis et Innaturalis by Johann Faust. (page 128 in “5 Early grimoires of the Olympic Spirits” – VAMzzz Publishing 2024).

The Olympic Spirits, also known as “Olympick Spirits” or “Olympian Spirits”, constitute a group of seven spirits documented in various Renaissance and post-Renaissance works on ceremonial magic. These works, including Theosophia Pneumatica, Arbatel de Magia Veturum, Vera atque brevis descriptio virgulae Mercurialis and the Faustian chapter Die Pentacula derer Sieben Olympischen Geister. The Secret Grimoire of Turiel also focusses on these spirits but references to this work remained absent until 1960, its original publication date. Notably, the work engages in plagiarism and revisits content from A. E. Waite’s 1898 publication, The Book of Black Magic and of Pacts, especially drawing from his translation of Arbatel de magia veterum, as well as borrowing from Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers‘s introduction to the 1888 edition of The Key of Solomon the King.

Furthermore, it exhibits a connection, if not a foundation, in a mid-nineteenth-century manuscript by Frederick Hockley, titled The Complete Book of Magic Science, which had multiple copies housed in various libraries. The Arbatel emphasizes that the universe is divided into 196 provinces, each governed by one of the seven Olympian spirits. These spirits, associated with the seven planets, the seven metals and the seven classic planet angels, are evoked for specific purposes, often in conjunction with the archangels, as detailed in rituals outlined in the Arbatel. The governors are served by various celestial entities, including kings, princes, presidents, dukes, and ministers, who command legions of subordinate Olympic Spirits.

Olympic Spirits and Planetary Angels

I came across some German writers of the 18th century who regarded the names of the Olympic Spirits as synonyms for the planetary angels Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, Haniel/Anael, Samael, Sachiel & Cassiel. Adding to the complexity is that the Olympic Spirits, though indeed often organized hierarchically alongside their corresponding angels, don’t always seem to represent the same power in a more concentrated form, as seen in common “protocol for magical hierarchies” where angels in Briah (the creative world) are above intelligences, spirits, and demons in the denser layers of Yetzirah (the formative world).

According to the Arbatel and Theosophia Pneumatica, Olympic Spirits rule entire sections of the universe, limited only by their planet-related psychospheres. The same applies to the traditional (arch)angels of the seven planets. However, when ritually summoned, Olympic Spirits are usually invoked for practical or material purposes, such as alchemically turning metals into gold or creating substances akin to the “philosopher’s stone” that can cure all diseases. In grimoires that invoke “demons,” such as the Goetia, the more practical properties of these beings are in the foreground, and they are therefore invoked for personal and material needs, rather than for spiritual purposes. So, what exactly are they? And that’s not an easy question to answer.

Johann Wilhelm Schmidt in Die Brüder St. Johannis des Evangelisten aus Asien in Europa : oder die einzige wahre und ächte Freimaurerei nebst einem Anhange, die Fesslersche Kritische Geschichte der Freimaurerbrüderschaft und ihre Nichtigkeit betreffend – Berlin 1803 describes the Olympic Spirits in comparision to the classic planetary angels as “ihre entgegengesetztte Herrscher” (“their contrary rulers,” “their antithetical rulers,” or “their opposing rulers.”).

In Les Clavicules de R. Salomon (Wellcome MS 4670, dated 1796), republished by Stephen Skinner & David Rankine in The Veritable Key of Solomon, Golden Hoard Press 2017, the Olympic Spirits rule the domain of their specific planet, while the corresponding angels rule the days connected to the planets.

Perhaps the most kinship with Olympic spirits is found in the planetary beings from medieval grimoires such as the Heptameron: entities that catalyse the materialisation of magical wishes, limited to the spectrum of the planetary psychosphere to which these entities belong.

The general consensus regarding the Olympic Spirits is that they first make their appearance in the Arbatel of 1575; however, their roots seem to delve even deeper. In the Höllen-Zwang oder Mirakul-Kunst und Wunder-Buch erroneously attributed to Johann Faust, and dated 1504 (the first work entitled Höllen-Zwang oder Mirakul-Kunst und Wunder-Buch was published in Lion, 1469), we encounter an extensive evocation rite dedicated to Aratron, who is described as “Aratron den Fürsten der Luft” (Aratron, Lord of the Air), commanding a large hierarchy of spirits. Aratron is particularly invoked for a spiritus familiaris who will fulfill specific wishes. The first entitled (Dreifacher) Höllen-Zwang is of Arab origin and was printed in Passau in 1407, long before Johann Georg Faust was born. (His year of birth is uncertain; either 1466 or 1480 or even 1490 are mentioned.)

Vera atque brevis descriptio virgulae Mercurialis is dated 1534 (Code C.M. 91 – Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig), although document C.M. 91 reads like an 18th-century copy of an earlier text. Therefore, we cannot be 100% certain whether the Arbatel of 1575 was the first document to publish information about the Olympic Spirits, as there is a strong suggestion that they were already known in the early 16th century or even 15th century. In the early 16th century Paracelsus (1493-1541) mentions Aratron, Bethor, Phaleg, Och, Hagith, Ophiel and Phuel as the spirits of the planets but does not yet use the term Olympian Spirits. With him, they are strongly associated with the metals associated with the planets and useful in performing alchemical-medical work based on planetary symbolism and psychospheres.

Sigil of Hagith, the Olympic Spirit of Venus

Olympic Spirits and their Rulership

Both the planetary angels and the Olympic spirits are invoked for their specific qualities, which, in turn, are directly linked to the respective psychospheres (sephiroth, hechaloth, seirai) of the planet they govern:

- Aratron, governing 49 Olympic Provinces under Saturn’s influence, imparts knowledge in Alchemy, Magic, medicine, and the secrets of invisibility. He bestows familiars, fertility, and longevity, possessing the unique ability to transmute coal into treasure and vice versa, even transforming living beings into stone. Aratron fosters reconciliation between subterranean spirits and humans, requiring invocation on Saturday’s first hour using the character provided by himself.

- Bethor, ruling 42 provinces tied to Jupiter’s influence, swiftly responds to evocation. He grants familiars, potentially extending life to 700 years, contingent upon God’s will. Bethor aids in discovering substantial treasures and facilitates reconciliation between air spirits and humans, ensuring accurate divination, transportation of precious stones, and the creation of miraculous medicines.

- Phaleg, overseeing 35 provinces under the governance of Mars, particularly excels in military affairs, fostering the advancement of soldiers or officers.

- Och, governing 28 provinces, embodies a spirit of perfection, extending life to 600 years with impeccable health. He confers outstanding familiars and perfect medicines, showcasing expertise in alchemy by transmuting substances into the purest metals or precious jewels. Och grants gold and a purse “springing with gold,” promising worship akin to a god by the world’s kings to those possessing his character.

- Hagith, ruling 21 provinces, focuses on venereal matters, providing faithful serving spirits. He transforms copper into gold and vice versa, enhancing the beauty of those possessing his character.

- Ophiel, with dominion over 14 provinces influenced by Mercury, imparts knowledge in various arts, including the instantaneous transformation of quicksilver into the Philosopher’s Stone. He also confers familiars.

- Phul, governing seven provinces under the Moon’s influence, transmutes all metals into silver, heals dropsy, and bestows water spirits in visible forms to serve humans. Phul prolongs life to 300 years.

These governors are served by kings, princes, presidents, dukes, and ministers, all commanding legions of inferior Olympic Spirits. The Arbatel provides instructions for evoking the governors, emphasizing the importance of conducting the evocation on the day and in the hour corresponding to the planet associated with the specific governor.

Olympic Spirits and their ritual fumigations

In both the Theosophia Pneumatica and the Arbatel de Magia Veturum, the number 7 (or multiples of 7) is repeatedly emphasized. As shown in the text above, the universe is divided into 196 provinces, which is the total sum of the number of provinces the Olympic Spirits are said to govern: Aratron – (7 x 7 = 49), Bethor (6 x 7 = 42), Phaleg – (5 x 7 = 35), Och – (4 x 7 = 28), Hagith – (3 x 7 = 21), Ophiel – (2 x 7 = 14), Phul – (1 x 7 = 7). Therefore, 196 numerologically adds up to 7: 1+9+6=16; 1+6=7.

Frederick Hockley, in his The Complete Book of Magic Science, listed recipes for invoking the Olympic Spirits. One should usually not take them too literally, especially when it concerns unusual ingredients such as the blood of a black cat or the brains of a magpie. Magical texts often use these kinds of bizarre descriptions as secret synonyms for certain herbs or stones. In German grimoires, for example, you may find

Blood from the loins – chamomile; Blood of Hephaistos – mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris, wormwood); Blood of a snake – hematite; Blood of the eagle – garlic; Hair of a baboon – dill tips; Sperm of Hercules – arugula; Hair of a lion – beet leaf; Bone of a medic – sandstone; Liver of a starling – valerian; Ovaries of one or two swallows – celery roots; Kidney of a hare – yohimbe. This, because I do not wish to stimulate any form of cruelty towards animals.

- Perfumes of Aratron: Saffron, with the wood of Aloes, of Balsam of Myrrh of Caurier. Add to it a grain of Musk, and ambergris, the whole, pulverized and mixed together in a paste.

- Perfumes of Bethor: Mastic of the East, chosen incense Cloves, powder of Agate. Beat all into a powder. Make thereof a paste with Fox’s blood and the brains of a Magpie.

- Perfumes of Phaleg: The head of a frog, the eyes of a bull, a grain of White Poppy, storax loadstone, Benjamin Camphor, pulverized into paste young barley.

- Perfumes of Och: Grains of Black Pepper, grains of Hogsbane, powder of loadstone, myrrh of the east, powdered made into paste with the blood of a Bat, and brain of a black Cat

- Perfumes of Hagith: Musk, ambergris, wood of Aloes, dried Red Roses, red coral, pulverized, made into a paste with the blood of Pigeon

- Perfumes of Ophiel: The seed of an Ash Tree, the wood of an Aloe: Storax and loadstone powder of blue and the end of a Quill, made into small balls.

- Perfumes of Phul: Euphorbe, Baellium, Sal Ammonian, Roots of Helibore, powder of a lodestone and a little Sulphur, made into a paste with the blood of a black Cat.

Wheel with sigilla of the Olympic Spirits

The Translated Grimoires

1. Claviculæ Salomonis, vel Theosophia Pneumatica – 1668

In 1686, the German version of the Arbatel (which is translated included in this book) was accompanied by another work, likely in the same volume, an adaptive titled Claviculæ Salomonis, vel Theosophia Pneumatica (“The Little Keys of Solomon” or “Theosophia Pneumatica“). Both works are featured in the third volume of Johann Scheible’s “Das Kloster”, aiming to illustrate the Faust-legend within the context of ancient magical literature. Notably, the Arbatel translation doesn’t acknowledge the prior Latin edition, and “Theosophia Pneumatica” does not explicitly claim to be an adaptation of the earlier work. The attribution to Solomon is clearly incongruent with the ritual’s spirit, revealing signs of ignorance.

Nevertheless, Theosophia Pneumatica was influenced not only by the Arbatel but also by other occult sources. The term Talmid, referring to the magical aspirant, is introduced in the adaptation and is absent in the original. According the Arthur Edward Waite, who discussed the Theosophia Pneumatica in his The Book of Ceremonial Magic, of 1913, Talmid has been said to represent a stage of initiation in certain occult societies of Islâm. The adaptation is well executed, enhancing clarity. The transcendental aspects are subtly emphasized, emphasizing that the exaltation of prayer marks the culmination of the entire Mystery. Such exaltation is promised to the true seeker, with a caution against undervaluing one’s prayers. This presentation surpasses the corresponding passage in the Arbatel. Additionally, there is an intriguing addendum on Transcendental Medicine, an original contribution, making it a unique element in the literature.

It is the Theosophia Pneumatica‘s appendix, which contains information not included in the Arbatel, thus positioning it as a unique grimoire on its own. Discusses is the tripartite nature of all things, from the Divine Triad to man. Man comprises the earthbound body, the elemental sensitive soul influenced by the stars, and the divine rational spirit directly from God. Describing the body as a dwelling for the soul and spirit, united by God, it highlights their daily struggle until the spirit prevails for regeneration. Two types of death are delineated: one from physical organ destruction and the other from astral influences destroying the sensitive soul. The skilled physician can discern such cases. The text advocates preserving the body against infectious diseases and countering malevolent star influences. However, diseases divinely inflicted may remain incurable despite the best remedies. The appendix, echoing Paracelsus’s terminology, adds a unique perspective to this work of which Arthur Edward Waite once wrote: “… it is unlikely that Theosophia Pneumatica will ever be printed in English”. Now 110 years later this remark is no longer valid, as the complete grimoire is presented here for the first time in translation.

Pneumatics

In the context of magical texts, especially in titles like Theosophia Pneumatica and Arbatel de Magia seu Pneumatica Veterum, the term “pneumatics” refers to a branch of philosophy or occult science that deals with spiritual or airy phenomena, often related to the breath, spirit, or vital force. The word “pneuma” in Greek means “breath” or “spirit,” and in a mystical or magical context, it can denote the spiritual or ethereal aspect of reality. “Pneumatics” in magical literature may encompass the study or practice of spiritual beings, divine forces, or the manipulation of spiritual energies. It often involves the understanding and harnessing of unseen forces, including those associated with the divine, spirits, or the breath of life. The term reflects a belief in the interconnectedness of the material and spiritual realms and the influence of spiritual forces on magical workings.

2. Arbatel de Magia Veturum (German version 1686) and its historical background

Arbatel de Magia Veterum is the title of a grimoire believed to have originated between 1550 and 1560. The author remains unknown. Initially comprised of nine parts, only the first segment has survived and become known. In 1565, the grimoire saw its initial printing under the title Arbatel de magia seu pneumatica veterum (“Arbatel of Magic or Pneumatics of the Ancients”) in what was referred to as the fourth volume of Agrippa von Nettesheim’s writings. This compilation does not originate from Agrippa himself; it was either ascribed to him by the publisher for economic reasons or was genuinely part of Agrippa’s library (suggesting its creation before 1535). A 1750 reprint is titled: Arbatel de Magia seu Pneumatica Veterum, tum Magorum Populi Dei, tum Magorum Gentium, pro Illustratione Gloriæ, et Philanthropias Dei, which translates as “Arbatel of Magic or Pneumatics of the Ancients, both of the people of God and of and of the Magi of the Gentiles, for the illustration of the glory, and the philanthropy of God.” The initial section of the Arbatel consists of 49 aphorisms and serves as an introduction to magic. It explores the summoning and belief in the so-called seven Planetary or Olympic Spirits, each attributed a name and specific characteristics.

The 1575 edition in Basel was titled Arbatel de magia veterum. Summum sapientiae studium (“Arbatel about the magic of the ancients. The highest pursuit of wisdom”). This primordial Arbatel was most likely edited by Theodor Zwinger the Elder (2 August 1533 – 10 March 1588) a Swiss physician and Renaissance humanist scholar, and published by Pietro Perna Calcei, in Basel, Switserland in 1575. The latter specialized in books that were often received as controversial, but in line with the printers motto: Verbum tuum lucerna pedibus meis (“Thy word is a lamp unto my feet”). The original author remains a mystery, but Joseph H. Peterson believes one Jacques Gohory (1520–1576) to be the most likely possibility. Gohory, like Zwinger and Perna, was a Paracelsian. Some German manuscripts produced shortly after the first publication of the Armadel attribute the work to Paracelsus, but without substantial evidence.

Sigil of Bethor, the Olympic Spirit of Jupiter

Pietro Perna (Villa Basilica, 1519 – Basel, August 16, 1582) was an Italian printer, and one of the most important printers in Basel during the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. His books promoted the development of Italian Protestantism, Socinianism, and the theory of tolerance. Perna, belonging to the Dominican order, converted to Protestantism as a disciple of the reformer Pietro Martire Vermigli, seeking refuge in Switzerland in 1542 with the help of Pietro Carnesecchi. Arriving in Basel in 1544, he founded a printing house in 1558. As a “book agent,” he built a network that facilitated the publication of works by Italian Protestants such as Vermigli, Pier Paolo Vergerio, Jacopo Aconcio, Bernardino Ochino, Lelio Sozzini, Sebastian Castellio, Celio Secondo Curione, etc. He published the editio princeps of the Greek text of Plotinus’s Enneads and printed important editions of authors like Niccolò Machiavelli, Jean Bodin, Francesco Guicciardini, Lodovico Castelvetro, Enea Silvio Piccolomini, and Francesco Petrarch. In 1560, he published the first Latin edition of Machiavelli’s “The Prince,” translated by the Protestant exile Silvestro Tegli, and in 1567-1568, the Latin translation of Francesco Guicciardini’s “History of Italy,” edited by Celio Secondo Curione. He also published the works of Paracelsus and many Paracelsians, as well as those of the main critic of Paracelsus, Thomas Erastus. He died of the plague and was buried in Basel in the Church of St. Peter. According to Joseph H. Peterson his publication of the Arbatel in 1575 caused a scandal and an investigation by the church.

In 1655, Robert Turner translated the Arbatel into English and added his own introduction. In 1686, the German version of the Arbatel was printed and published by Andreas Luppius in Wesel, Duisburg, and Frankfurt, based on the Latin 1575-version. As will be evident in this book Claviculæ Salomonis, vel Theosophia Pneumatica was largely based on this work, which in turn was reprinted by Johann Scheible in Leibzig, 1846. This version has extra information added at the end of the work formatted into two addditional chapters. The first one Geheimnüßdes Nahmens Gottes / Welchen die folgende 72. Völcker mit Vier Buchstatcn schreiben und nennen, contains the 72 four-letter names of God as originally presented by Athanasius Kircher. The final chapter Eine sehr hohe und geheime Kunst / so das übertrefflichste und vornehmste Theil Salomonts tst. contains a complex sigil in the neo-Faustian style.

The mysterious name “Arbatel”

In the quest to unravel the enigmatic origins of the Arbatel scholars have proposed various interpretations of its title. A. E. Waite posits a connection to the Hebrew ארבעתאל (or Arbotal), potentially denoting an angel from whom the author claimed to have gleaned magical knowledge. Adolf Jacoby, on the other hand, suggests a reference to the Tetragrammaton. This is plausible as ארבעת אל, vocalized as “arbath el,” translates as “the Four Gods” or “the Fourfold God” (YHWH). It is important to realize that the Arbatel is assumed to have once been embedded as a chapter in a much larger volume. The central focus of the Arbatel lies in exploring the intricate relationship between humanity and celestial hierarchies, presenting the Olympic spirits. Despite its Christian nature, the work, according to A. E. Waite, distances itself from black magic and exhibits no ties to the Greater or Lesser Keys of Solomon. In a departure from conventional grimoires, the Arbatel encourages magi to actively engage with their communities, advocating for kindness, charity, and honesty over arcane rituals. Biblical references abound in the text, reflecting the author’s extensive familiarity with scripture. The Arbatel’s philosophical underpinnings are deeply intertwined with the teachings of Paracelsus, who introduced the term “Olympic spirits” and influenced its understanding of elementals, the macrocosm and microcosm, and a blend of experimentation and deference to ancient authorities. Rooted in classical culture, including Ancient Greek philosophy, Sibylline oracles, and Plotinus, the Arbatel also draws inspiration from contemporaneous theology and occult philosophy, exemplified by figures like Iovianus Pontanus and Johannes Trithemius. This broad and profound cultural foundation aligns with the works of Jacques Gohory, providing potential evidence for Peterson’s theory of Gohory’s authorship.

Sigil of Phul the Olympic Spirit of the Moon

3. Fausti Höllen-Zwang (Aratron-evocation)

Wittenberg-version of Fausti Höllen-Zwang oder Mirakul-Kunst und Wunder-Buch, (“Faust’s Coercion of Hell, or Miraculous Art and Wonder-Book”), was published in 1504, and republished in Stutgard by Johann Scheible in1849. Faustian Grimoires is an umbrella-term for a lot of grimoires, mostly erroneously attributed to the historical Faust. Johann Georg Faust, also known as Georg Faust (born probably around 1480 in Knittlingen, with various sources also mentioning Simmern, Roda, and Salzwedel; † around 1541 in or near Staufen im Breisgau), was a wandering miracle healer, alchemist, magician, astrologer, and fortune-teller. His life is considered the historical prototype for the Faust legends, and consequently, the renowned works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Faust I and Faust II. In all accounts of Faust written during his lifetime, the historical Faust always appears with the first name Georg or Jörg. It is only more than two decades after his death that a Johann Faust is mentioned, possibly because Faust himself omitted the commonly used first name Johann.

The historical Faust appeared in many cities in the southern German region. He presented himself as a philosopher, miracle healer, alchemist, and fortune-teller. However, many regarded this “magician,” who acted as a charlatan and impostor, as nothing more than a fraud. He faced particular hostility from clergymen. There are no confirmed records of Faust’s activities before 1506. In contrast to other scholars of his time, such as Agrippa von Nettesheim, Trithemius, and Paracelsus, who were also considered magicians, Faust was primarily known as a practitioner.

The Fausti Höllen-Zwang oder Mirakul-Kunst und Wunder-Buch, which I have translated for this compilation centered around the Olympic Spirits, is an intriguing work within the broader context of the Faust discussion. What sets it apart are the sigilli presented in the work, which exhibit a distinct style compared to most Faustian works, appearing much older. The text of this work is concise, consisting of brief evocation instructions. The primary spirits to invoke are Pluto and Aratron. Interestingly, in this work, Aratron does not manifest as the Spirit of Saturn but rather as the Spirit of the Air, who is invoked by the magician for obtaining a familiar spirit (spiritus familiaris). The evocation rite is presented in detail, complete with the specific sigilli for Aratron, distinct from the usual Aratron sigilum. One sigilum is intended for inscription on a hazel-wood twig shaped like a fork, while the other is to be written on parchment using raven’s blood. Notably, among the seven entities later known as the Olympic Spirits, only Aratron is mentioned in this manuscript.

4. Die Pentacula derer Sieben Olympischen Geister

This chapter is part of the Faustian work Magia Naturalis et Innaturalis, a grimoire published in 1749 and reprinted in 1849 by Johann Scheible. It features unique and beautifully composed sigils for summoning the Olympic Spirits. The complete work, authored by an anonymous writer, is renowned for its complex content, incorporating various magical and alchemical elements. While it is associated with the Faustian legacy, it’s crucial to recognize that the historical Faust did not author it, and it is likely not older than its initial publication in 1749, although the composer of Magia Naturalis et Innaturalis adopted much material from older sources.

5. Vera atque brevis descriptio virgulae Mercurialis

This last work, of which the complete title translates as A true and brief description of the Mercury rod, and the method of preparing it as found, and by its means, many treasures are uncovered” employes the Olympic Spirits’ assistance for alchemical purposes. In this handwritten text of this alchemically oriented grimoire, certain words were misspelled, rendering some terms undecipherable or inaccurately reflecting the intended meaning. Based on the presented 1532 I had to make an attempt for a logical restoration of the original Latin, before I could make the English translation. Because the original text is short, I concluded the restored Latin version, followed by the translated version – intentionally a bit ‘rough’ to make sense of the text.

It is evident that the content revolves around the creation of a rod made of the composite metal ELECTRUM. This metal (here) comprises all planet-related metals, and the process involves evoking the planetary spirits and engraving their sigils into the rod. For the relationship between Olympic (Planetary) Spirits and metals.