Beyond Official Narratives: The Persistence of Pagan Spirit Beings in European Culture

Until the era of industrialization, Europe was predominantly a mosaic of agrarian cultures marked by local fertility-related rituals. Agricultural demons played a crucial role in daily life and every year they had to be appeased. Equally significant were the practices of maintaining household spirits or amicable farmyard guardians. The rituals and lore surrounding these spirit beings permeated every corner of Europe, showcasing considerable overlap. Lingering into the 19th and early 20th centuries, some of the last vestiges of such practices manifested in Eastern Europe and Germany in rituals for the field demons, while in Great Britain the kern baby ritual [1] was still performed.

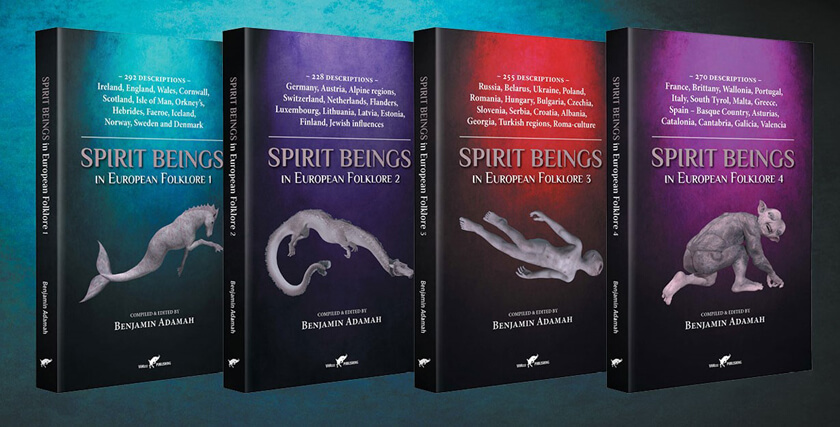

- Adamah, B. (2022). Spirit Beings in European Folklore 1.

- Adamah, B. (2022). Spirit Beings in European Folklore 2.

- Adamah, B. (2022). Spirit Beings in European Folklore 3.

- Adamah, B. (2022). Spirit Beings in European Folklore 4.

Further east, even in contemporary times, various ethnic groups, officially adhering to Russian Orthodox or Islamic faiths, persist in practising age-old rites for ensuring a fruitful harvest and addressing other concerns. Pagan deities and spirits survived centuries of state religion and even the era of communism. Among these ethnic groups are the Chuvas, the Mari El, Udmurt, and the Mordvin. In addition to entities that provide fertile fields, crop protection and protect homes and hay barns, rich lore included water spirits, alps, incubi/succubi, mountain spirits, forest entities, vampire spirits or vengeance spirits, sea spirits and various types of nature spirits, some of which originated with certain spirit beings from ancient times. The lares, penates, and lemures of the Romans, for example, fulfilled the roles of nurtured or, in the case of the lemures, unwelcome home spirits, just like household spirits and unwanted nocturnal visitors like alps and vampires emerged in medieval times. In Eastern and Mediterranean Europe, many water spirits, tree, and well spirits are linked to the nymphs and dryads of ancient Greece.

What, precisely, are these spirits or demons that managed to escape the cultural cleansing of paganism by the church for centuries, challenging the official (monotheistic) teachings? Do these beings exclusively belong to specific regions, or do we also encounter entities with similar characteristics and behaviours throughout Europe under different local names? Identifying them is a straightforward task, but classifying them poses a significantly more challenging question, given that several spirit beings underwent remarkable evolutions.

Introduction

The general history lessons most of us received in school primarily consisted of a lengthy enumeration of various official events, often revolving around political turning points or shifts associated with disasters such as the plague, invasions, revolutions, or wars. Our understanding of patriotic history was shaped by the same schematic approach. The issue with this historical narrative lies in its official nature, a perception framework usually tied to national or religiously coloured identity politics. In some cases, motivations may be even more questionable, driven by economic, juridical and personal PR-interests, as exemplified by the official historiography of World War II prescribed by the Rockefellers in 1946. Fortunately, in recent decades, micro-history has gained prominence, shedding light on themes more deeply intertwined with the actual reality and lives of people during specific periods, instead of pimping the recurring simulated (official) realities orchestrated by political and religious leaders. Case in point are the fascinating works on benandanti and northern Italian witchcraft by Carlo Ginsburg [2] and the folkloric research of Claude Lecouteux [3].

Another feature of history is that only a very small part of it deals with the rural areas, despite the fact that the old Europe was all about agriculture. Throughout my years of investigating the role of spirit-beings in European folklore, I couldn’t help but observe that, despite the official narrative of Europe being Christianized, pagan practices endured on a major scale, especially in the rural areas. These persisted of course in centuries-old public festivities, now very useful to attract tourists, but also more private, in the ritualistic appeasement of entities from the ‘invisible’ realms, or through specific protective measures prompted by the fears they invoked.

Transcendent vs immanent

In my research, I found it necessary to delineate between “spirit beings” and “gods.” However, in many instances, this boundary is far from watertight. This is particularly evident with various chthonic Eastern European and Basque entities, which, under the influence of Christianity, were devalued to lower-nature beings. Simultaneously, many gods were already so immanently intertwined with natural phenomena that in modern times, they might be classified as “daemons” or “demons” rather than “gods or goddesses,” given their often explicit earthly manifestations.

Typically, a god or deity is a supernatural entity worshipped by believers as a powerful, superhuman, often immortal being, responsible for certain aspects of reality or even reality as a whole. Entities at the daemon/demon, nature-spirit, or phantom level are generally perceived to exist more closely to our physical realm, which is reflected in their more limited capabilities and tasks, which are characteristically mostly linked to concrete results. The terms “demon,” “daemon” (minor god), and “spirit” or “spirit being” are often interchangeable. Examples include the Spanish term duende, the Basque irelu, the fairy, faery, and fee of Celtic Britannia, Ireland, Scotland, and France, as well as the Baltic mātes, among others. Chthonic gods typically hold an intermediate position between the celestial gods and the numerous spirit beings found in folklore.

Unlike the devilish “demon” of the state religions, in folk beliefs, a “demon” does not necessarily signify “evil.” While there are exceptions, in most cases, a demon is just a raw force of nature, possessing both benevolent and malevolent aspects, just like humans and animals do. These aspects are usually directly influenced by human interaction in their presence, especially when humans share the same living spaces, such as household demons or spirits inhabiting barns, etc. In general the worship of these beings simply consisted in keeping them friendly with offerings, certain rituals and obeying specific rules. This would appeal to the benevolent side of these creatures and thus keep the family safe and prosperous.

Many creatures unfairly bear a negative image due to centuries of Christian demonization politics and the inherent dictate that equates “the divine” with “the transcendent.” Within this exclusively patriarchal state-religions-related doctrine, there is no room for anything divine or supernatural that manifests itself as immanent or earthly. Adding to the complexity of distinguishing gods from lower classes of spirit beings is the fact that nature demons, various nocturnal visitors, and household-spirits often emerge from the spirits of deceased people or even aborted fetuses. Typically, these are individuals torn from their social tradition and security by trauma, injustice, grief, or neglected baptismal or funeral rites. In cases where one of the many European varieties of alp-type creatures takes centre stage, it may even be the projected etheric double of a consciously living person that attacks during sleep.

While the influence of the church is declining, industrialisation, technological and screen-dominated digital lifestyles, along with a correlated mindset, have infected society with a new “tunnel-vision rationality” that, ironically, with the exception of Netflix, leaves little room for mysterious entities like goblins, elves, or hulder. Particularly in the Slavic countries, once covered with dense, pristine forests, a clear correlation can be seen between the industrial felling of trees and the decline of belief in nature spirits such as the leshy and many others. Nevertheless, this trend is relatively new in human history. In the early 20th century, many entities were still integral to daily life in rural Europe. Only a few decades ago, one could still observe three deliberately left-over ears in cornfields after harvest, as a contract with the local field-spirit. Not long before that, people took precautions against nightly visits from alps or adhered to specific rules in Russian bathhouses to avoid annoying the bannik who resided there at night.

Until the 19th century, on many farms in Eastern Europe, it was vital for prosperity and protection to maintain friendly relations with the barn-demon or household-spirit (domovoy, stopan, zmiya domakinka, chuvarkuħa). Thanks to especially the German folklorist Wilhelm Mannhardt (1831 – 1880) the illustrious names of many German field spirits were preserved, like Roggenwolf, Kornhund, Erntebock, Sauzagel, Baumesel, Kornmädel. Even in the 17th and 18th centuries, vampiric revenants or etheric vampires were a serious concern in many parts of Iceland, eastern Europe, parts of Germany, the Balkan countries, and Greece. Some well-documented vampire cases still raise unanswerable questions.

The household spirit was as important as the field spirits. As Lecouteux pointed out, during medieval times, the household spirit behind the fireplace held as much value to the family as a smoothly functioning internet connection does today. When people moved from one home to another, great care was taken to ensure that the spirit accompanied the family to their new place, taking up residence behind the stove. The hook hanging over the fireplace, imbued with the essence of the household spirit, became the most significant object in the house.

Traditional beliefs in Russia

Traditional beliefs have persisted most strongly in Eastern Europe, at times blending with Tengrism, the Turkish-Mongolian form of animism. The Chuvash people, residing in the Chuvash Republic of Russia, practice a form of paganism centred around the veneration of nature, household spirits, and ancestors. Their rituals include ceremonies held in sacred places, such as groves and natural springs. The Mari people, living in the Mari El Republic of Russia, worship a variety of deities associated with nature, fertility, and household spirits. (Neo)paganism in the western half of Russia is especially blooming among the Uralic speaking peoples. Uralic neopaganism comprises modern movements dedicated to reviving the ethnic religions of Uralic language-speaking communities. This resurgence gained momentum in the 1980s and 1990s, coinciding with the dissolution of the Soviet Union and aligning with the ethnonational and cultural revival among the Finnic peoples of Russia, Estonia, and Finland. Notably, neopagan movements in Finland and Estonia trace their origins back to the early 20th century.

Erzyan native religion, represents the modern revival of the ethnic religion of the Erzya Mordvins, a Volga Finnic ethnic group residing in the Republic of Mordovia within Russia or in its bordering lands. The Erzyan faith (Erz. Ineshkipazněń Kemema) is a traditional polytheistic religion of Erzians, containing elements of pantheism. The name derives from the supreme god’s name, Ineshkipaz. The Erzian faith is widely practiced among the Erzians, alongside Orthodox Christianity, within the framework of dualism. Traditional Erzyan cults are often held during the twelve festive days. 2% Of the Erzians adhere to pure non-Christianity and do not practice Christianity. They have ceremonies for trees, the dead, and the Peace Tree and Big Bird are important sacred elements. Gods in Erzyan are divided into earthly and heavenly. Earthly ones are those surrounding a person, related to the house – Kudava (kudo – “house”), Kardazawa (kardaz – “garden”), Yurtava (jurt – “foundation of the house”). Some earthly gods personify fertility: Norovava (norov – “fertility”), Paksyava (paksä – “field”), Viryava (viŕ – “forest”, ava – “woman”). Heavenly gods also have their own classification, depending on the performed “functions” and the degree of power. In addition to the only eternal god Erzya, they recognize good and evil spirits created by him. According to folklore, spirits reproduce like humans, and there are many of them in the world. Invisible deities are present everywhere, executing the command of the supreme god or appointed by him to rule over a specific part of the universe. The Erzyan concepts of time, space and consciousness are very sophisticated.

The Udmurts, an ethnic group in Russia, have a history of practicing a blend of traditional Finno-Ugric pagan beliefs and influences from other religions, including Islam and Christianity. The Udmurts’ traditional belief system comprises an archaic pantheon of gods and spirits associated with nature, ancestors, and various aspects of daily life. Inmar, a major god in Udmurt mythology, is often linked to the sky, considered the father of all gods and associated with the celestial sphere, thunder, lightning, and rain. The Goddess Umai (Umay, Umi, Umai-Poar) is often associated with the earth and fertility, revered as the mother of all living things and worshipped as a protector of women, children, and the household. Other significant gods include the weather-god Kuaz, creator-god Kildysin, Kul-Ekva (Kul-En, Kul-Lar), a god of the hearth and home invoked for protection and well-being within the household. Numi-Torum serves as a collective term for the spirits of deceased ancestors, emphasizing the integral role of ancestor worship in Udmurt paganism. Rituals are conducted to honor and seek guidance from these ancestral spirits. Izto is a spirit associated with the forest and wildlife, symbolizing the close connection with nature in Udmurt paganism. Tul is a spirit linked to the hearth and fire, invoked for protection and prosperity in the sacred space of the household. I provided more detail on the Erzyan Mordvins and Udmurts because their religions are based on a spiritual template typical of what is often summarized as the ‘Old Religion,’ an animistic template that has been more or less consistent across, not only Europe, but Eurasia in general. It usually features a sky god, an earth goddess and numerous nature gods and spirits, with significant emphasis placed on the worship of ancestors.

Vodyanoy on old Russian postcard – before 1917

In 1992, Raisa Stepanovna Kemaykina, an activist, Erzya language poet, and leader of the Erzya native religion celebration Rasken Ozk, responded to a question about her attitude towards Christianity in an interview with the Chuvash newspaper Atlas with the following declarations:

I am strongly opposed to it. In its role as the official state religion of Russia Christianity suffocated the religions of other nations, transforming them into involuntary spiritual slaves. Russia has long been called ‘the prison of the nations’. I think this is too mild. It is worse than a prison. Sooner or later people get out of prison and become masters of their own fate again. A prisoner is someone who has lost his or her freedom temporarily. But a slave is not a prisoner – he doesn’t even desire freedom. Over the course of many centuries Christianity has bred our peoples into slaves, depriving them of freedom of thought and reducing them to the level of submissive cattle. In the Erzya religion the relationship between God and human beings is different from that in Christianity. It is deeper, more humane, more beautiful … In our religion a person’s worth is not killed or suppressed, but extolled. You never hear things like ‘you are God’s slave’, or ‘turn the other cheek’, or ‘if someone takes your coat give them your shirt as well’, or ‘bless your enemy’.[5]

In 1992, Kemaykina orchestrated the inaugural national Pagan ritual, a remarkable event sponsored by Erzyan businessmen, marking the resurgence of ancient traditions after decades, if not centuries. The neighboring villages rediscovered long-forgotten Pagan prayers, and Kemaikina was officially recognized as the first priestess of the Erzya people. The televised coverage of this and subsequent national worship ceremonies sparked enthusiasm across the republic, prompting discussions on the “Pagan question” from the remotest villages to university auditoriums.

In Lithuania and Latvia, there has been a robust revival of Baltic pagan traditions, often referred to as Romuva. This revival involves the worship of ancient Baltic deities and spirit beings, with ceremonies held in sacred places such as hillforts. Baltic neopaganism represents a category of indigenous religious movements and the term “paganism” is in fact rejected. Originating in the 19th century, these movements faced suppression under the Soviet Union but have seen a resurgence since its collapse. This revitalization aligns with the broader national and cultural identity awakening among the Baltic peoples, both in their homelands and among expatriate communities, with notable connections to conservation movements. Romuva seeks to revive the traditional ethnic religion of the Baltic peoples by rekindling the pre-Christian religious practices of the Lithuanians. It asserts continuity with living Baltic pagan traditions embedded in folklore and customs.

Kittelsen-Nøkken (water sprite)

What are these entities, and how do we wish to define “real”?

In 2022, I released a four-volume encyclopedia, Spirit-Beings in European Folklore. This series details a total of 1,045 distinct spirit beings spanning various regions, including the British Isles and Scandinavia, German-speaking Europe, the Baltic States, the Netherlands/Flanders, Eastern Europe, and Southern Europe, encompassing Wallonia. One crucial motivation for this project was the question: Do these spirit beings exclusively belong to specific regions, or do we also encounter entities with similar characteristics and behaviours throughout Europe under different local names? It turned out that, while numerous spirit beings are distinct to specific geographical locations and their cultural traditions, many entities known by different names are essentially the same, often accompanied by similar folkloric rituals. Measures against alp-attacks are more or less consistent across the European mainland, as are, for example, the changeling-phenomenon and the method of determining whether a baby is a changeling by making it drink from an eggshell. This tradition spans from Spain to Eastern Europe. The British Lady Midday, an often dangerous female spirit that appears in cornfields at noon on hot summer days and is associated with sunstrokes or worse, is known all over Middle Europe as well. The Germans know her as die Mittagsfrau or Roggenmuhme, while in Polish, she is addressed as Pŕezpolnica. Moreover, there are striking similarities between various European versions of gnomes, goblins, or dwarfs and many varieties of the ‘Little People’ among the First Nation Americans, known by virtually every tribe long before the first colonists arrived.

The inevitable (but also rather useless) question that pops up when compiling a comprehensive collection of folklore creatures is: ‘Are these beings real, beyond the realm of anecdotal data and individual experiences?’ I prefer to approach the subject of folkloric creature data as a phenomenon that is just there, like the smoke of an invisible, intangible fire. Just as – according to Martin Heidegger – the genius loci of a certain area inspires and shapes in an intangible way the culture of a people living there. All we get to see of a culture-forming process is the symptomatic layer that eventually consolidates into an ongoing tradition. The problem of “real” or “not real”, of course, lies in the preceding question: What precisely defines “real”? Is there, in fact, anyone capable of formulating an absolute definition of “real” when, from an earnest examination of our history, the concepts “real” and “true” continually shift, akin to a chameleon on a kaleidoscope via arguments that do not always stay as close as possible to what is plausible from a lateral intelligent point of view?

People usually tend to categorize things as “real” by measuring their conformity to the current established consensus, which is always influenced by corporate structures, (religious) customs, repetitive media messages, or (would be) rationalized viewpoints. This process often sidesteps critical thinking and independent judgment. Instances or encounters deemed anecdotal, which incidentally constitute a substantial portion of folklore concerning spirit beings, face dismissal or mockery when they don’t align with the prevailing consensual framework. The often Zeitgeist-correlated consensus typically prevails over an acceptance (or even an investigation) of raw, unexplainable experiences beyond the current consensual agreement grid as the latter can challenge established mindsets and one’s identity profile, or more often, the profile of a group or institution. Modernism has afflicted our minds with fragmented modes of perception and constrained, one-sided cognitive validation methods. However, as the notions of “real” and “true” are intricately connected to the concept of “understanding” it is important to realize the fact that “understanding” is not exclusive to the left hemisphere of the brain. To illustrate this: although we readily accept art for example as “real,” studying the chemistry of pigments does not make someone an authority on paintings. Indeed, the very thing that can touch us and move us so deeply in a great work of art resides, by definition, in a dimension, which remains elusive to any attempt to subject it to exact laws and any other modern verification method. Nevertheless, what is technically nothing but an arrangement of pigments can give us a very “real” experience. Yet this “real,” which cannot be measured but only experienced, still awaits a true emancipation of its reality.

So, despite a plethora of genuine video footage depicting paranormal phenomena such as ghosts, apparitions, poltergeist activities, and moving orbs, Western civilization tends to dismiss those who believe in (read: experienced) such occurrences as deranged or irrational. In contrast, I once read a scientific study that confirmed that most people experience at least one paranormal encounter during their lifetime. Something that they can neither deny nor explain conventionally. And one day things may change. In a very recent study, it is advised to accept (genuine) paranormal experiences as indeed ‘real.’ [6] When exceptions challenge the consensus, true rationality should prompt a revision. Isn’t that what true science distinguishes from scientism?

Let’s get a little more concrete. The ‘medieval’ incubus/succubus is a creature defined by Australian metaphysician and OBE expert Robert Bruce as a special kind of astral wildlife. Many people, both women and men, still have experiences with this entity — two I know personally. The same goes for the alp, which also sits on its victim at night but usually causes nightmares instead of an extreme erotic experience, usually ending in an intense orgasm. Children under the age of three often see nature spirits, Elementals, dwarf-like creatures, etc. My son, who, in his early childhood, had clairvoyant abilities that regularly caused him a lot of fear, could see many creatures that were invisible to the average adult. Seeing ghosts or some kind of phantom is a common experience shared by many people all over the world. The last person from whom you would expect anything unusual in this regard might be an accountant. Nevertheless, I had an accountant whose life turned upside down after he encountered a kobold-like entity in a shed, clearly visible as if it were real, that started to take his energy. This experience opened his mind to other things than working with numbers all day. A door he never knew existed had opened, and the last time we met, I gave him a book about Findhorn.

Classification

Folklore, especially pertaining to nature spirits, fairies, vampiric beings, goblins, revenants, and others, is not an exact science. While it’s possible to create a grid of classes and species, Wilhelm Mannhardt noted that many creatures undergo some form of evolution, particularly in their interactions with the human world. For example, certain forest spirits may transform into field spirits and, from there, transition into spirits that protect farmyards or households. In Germanic, Celtic, Baltic, Scandinavian, and Slavic regions of Europe, many creatures acting as barn, farmyard, or stable spirits maintain a dual nature, remaining half-wild. According to folklore, these beings reward positive behaviour, respect, rituals, and food offerings but can become troublesome or even life-threatening when their rules are violated. In many cases, they simply leave, taking their gift of prosperity with them. This ‘formula’ is consistent in the lore of spirit beings of the household, barn, yard, or field types all over the European continent.

Various spirits fall under general terms such as fairies, goblins (prank-pulling dwarf-like creatures), gnomes or dwarfs, trolls, water sprites, mermaids, vampiric revenants, phantoms of dead children (like the myring), elves, weather spirits, nymph-like creatures, and more. Most of these spirits defy easy categorization into a single class and often fit into two or more different categories. While this classification is somewhat arbitrary, one could assert that roughly the following “classes” are the most notable.:

• Alp or Mare-type spirits

• Aquatic nymphs and nymphs-like spirits

• Aufhocker-type spirits

• Banshee and Dames Blanches type spirits

• Basque ireluak

• Bogeys

• Changeling-type spirits

• Chthonic gods

• Dangerous water spirits

• Evil spirits of the dead

• Evil nocturnal spirits

• Female vampiric beings

• Field spirits

• Forest spirits

• Grim-like phantom dogs or creatures

• Hags or hideous Crone-type child luring spirits

• Household spirits

• Icelandic spirits

• Incubus-Succubus type spirits

• Kobolds or Dwarfs

• Local spirits

• Midday women

• Mountain spirits

• Neutral or friendly water spirits

• Prankster spirits

• Sea spirits

• Shape-shifters

• Spirits evolved out of spirits of dead children

• Spirits born from a rooster-egg

• Spirits rooted in Greek-Etruscan-Roman culture

• Spirits rooted in Jewish culture

• Spirits rooted in Turkish-Mongolian culture

• Spirits that are derivatives of ancient pagan gods

• Tree spirits

• Vampiric beings or revenants

• Weather and wind spirits

• Were-animals, like werewolves

• Wild men and Wild women

• Wilderness demons leading people astray

• Will-o’-the-wisps

gnome; illustration taken from Apel les Mestres

A subtle distinction emerges in later times between spirits within the Indo-European traditions and cultures and those of the Basque people. The Basques boast a folklore rich in ireluak or genii, which, in most cases, hold a dual position—being both a unique or local entity and a manifestation of one of the gods or goddesses, often involving the goddess Mari, regardless of whether the irelu is masculine, like a bull or billy goat. In this context, Mari and her spouse Sugaar, for example, are not gods in the classic Indo-European supreme celestial sense but are more akin to major devas or daemons representing and influencing various weather phenomena and other manifestations of nature. They are immanent gods strongly connected to the Earth and wild nature, as are their manifestations in the many different ireluak. This understanding of immanent gods was not exclusive to the Basques. In fact, all of pre-Christian Europe had similar systems of nature gods, many of whom were more immanent nature forces than transcendent heavenly beings.

Many spirits, also act as bogeys [7], playing roles in tales to keep children away from dangerous places. The alp/mare-type spirit, found in various variations across the continent, often merges with the incubus/succubus or the hag. Useful household spirits may also act like goblins, playing pranks or causing poltergeist-like phenomena. Many spirits of different types can manifest as will-o’-the-wisps, and many types of fairies and trolls are known to replace children with changelings. Various nature spirits, including water sprites, may also act as vampires, which in turn often merge with the werewolf. While vampire/werewolf/revenant-type creatures are typically harmful, most spirits exhibit a dual nature, acting as both a blessing and a curse for humans. This duality is especially pronounced when spirits enter into relationships with human partners, as seen with water-nymphs. Sexual relations with humans are occasionally described, rarely resulting in a special hybrid offspring called a cambion. Iron, the crowing of roosters at dawn, modern technology, and church bells are nuisances to most spirits, potentially driving them away permanently, much like rude human behaviour.

Nature spirits, incubi, alps, fairies, and particularly the vampiric revenants of Eastern Europe, the Balkans, Scandinavia, and Iceland aren’t always composed of a diffuse spirit substance or ethereal fabric; they can materialize and manifest in a very physical way. This is evident in creatures like the German Aufhocker, which jumps on the back of a nocturnal wanderer and grows heavier and heavier, and the Celtic brook horses of Britain, Ireland, Scotland, and the islands between Scotland and Iceland. The ability to materialize in a more condensed and physical state and to dematerialize quickly is a characteristic shared by many spirits described in European folklore.

Agricultural Mermaids and Fishy Leprechauns

Images of spirit beings can change quite radically. Very illustrative are the Eastern European mermaid, the rusalka, and the Irish kobold, the leprechaun. The rusalka (pусалка: Mermaid; pl.: rusalki) is a female water-spirit of East Slavic mythology. The concept of the mermaid that exists in the Russian North, in the Volga region, in the Urals, in Western Siberia, differs significantly from the Western Russian and Southern Russian ones. It was believed that mermaids/rusalki looked after fields, forests, and waters. Before the twentieth century, in the northern provinces of Russia, the word pусалка was perceived as “bookish,” “scholarly.” Earlier this character was known as vodyanitsa, vodyaniha, or vodyantikha (Russian: водяни́ца, водяни́ха, водянти́ха; meaning: “she from the water” or “the water maiden”), kupalka (Russian: купа́лка; “bather”), shutovka (Russian: шуто́вка; “joker”, “jester” or “prankster”) and loskotukha, shchekotukha or shchekotunya (Russian: лоскоту́ха, щекоту́ха, щекоту́нья; “tickler” or “she who tickles”). In southern Russia and Ukraine, the rusalka was called a mavka, and the Serbian vilas are also akin to the rusalki. Specifics pertaining to rusalki differed among regions regarding their looks or behavior. In most tales, they lived without men. In stories from Ukraine, they were often linked with water. In Belarus, they were linked with the forest and field. In Poland and the Czech Republic, water-rusalki were younger and fair-haired, while the forest-rusalki looked more mature and had black hair – but in both cases, if someone looked up close, their hair turned green, and their faces became distorted. In Polish folklore, the term rusalka could also stand for boginka, dziwożona, and various other entities. In some beliefs, rusalki were attributed the ability to change into werewolves or other were-animals. It was believed, for example, that they could take the form of squirrels, rats, frogs, birds (Ukraine), or appear as a cow, horse, calf, dog, hare, and other animals (Poland).

The Anglo-Irish word leprechaun [8], used for the most popular dwarfish, humanoid spirit of Ireland, has a complex etymology. Scholars maintained that leprechaun descended from Old Irish luchorpán or lupracán, via various (Middle Irish) forms such as luchrapán, lupraccán, (or luchrupán). Leprechaun or lepricaun was derived from the Irish leith brog, i.e., the One-shoemaker, since he is generally seen working on a single shoe. It is spelled in Irish leith bhrogan or leith phrogan, and is in some places pronounced luchryman (O’Kearney in Feis Tigh Chonain). Another theory states that “leprechaun” may come from the Irish root lú, meaning “smaller,” and from the Irish root chorp, derived from the Latin word “corpus,” meaning “body,” but the latest academic research concluded that Leprechaun is originally not an Irish word. Research published in 2019 by a team of five academics, from Cambridge University and Queen’s University Belfast, suggests that although “leipreachán” has been in the Irish language for a long time, it comes from luperci, a group linked to the Roman festival of Lupercalia. The feast included a purification ritual involving swimming and, like the luperci, Leprechauns were also associated with water in what may be their first appearance in early Irish literature. The earliest known reference to the Leprechaun appears in the medieval tale known as the Echtra Fergus mac Léti (Adventure of Fergus son of Léti) of which there are two widely divergent versions: one from the 7th or 8th century, and a burlesque, Rabelaisian one from the 13th. The text contains an episode in which Fergus mac Léti, the legendary King of Ulster from 26 – 14 BC, falls asleep on the beach and wakes to find himself being dragged into the sea by three water-sprites or lúchorpáin. He captures his abductors, who grant him three wishes in exchange for their release.

Conclusion

In monotheistic religions there is in principle no room for, not so much the belief in spiritual beings other than God the creator, but above all in the emancipation of their existence in spiritual reality, as these beings are inseparable from the displaced polytheistic and animistic dimension. This dimension has been systematically eradicated century after century in favour of the dominant state religions with their centralized power, particularly Christianity in Europe, which has consistently sought to eliminate every aspect of the ancient European faith. On the contrary, in the rural and heavily wooded areas of Europe, there exists an incredibly rich folklore surrounding various positive, negative, or neutral spirit beings that have remained integral to local spiritual activities until about a century ago. Some of these creatures exhibit uniqueness specific to certain regions or cultures, while numerous others are variations of the same creatures recognized by distinct local names, and they hold a prevalent presence in folklore across Europe.

Although the folklore of these beings reached a low point in the 19th and 20th centuries, there was a simultaneous effort by various authors to extensively document their folklore. Additionally, a revival of indigenous religion took place in the relatively newly Christianized Baltic states as early as the 19th century, followed by similar movements across Europe in the 20th century. The revival continues most prominently among the Uralic-speaking peoples of Russia, Eastern Europe, Finland, and the Baltic states. The catalyst for this resurgence was the fall of the Soviet Union, leading to the revival of national-cultural consciousness among many ethnic groups.

In the Baltic states and among the Erzya, there is a heightened awareness of the political role of Christianity. (During Pope Francis’ visit to the Baltic states in 2018, the Dievturība and Romuva movements jointly sent a letter to Pope Francis, urging fellow Christians to “respect our religious choice and stop hindering our efforts to achieve national recognition of the ancient Baltic faith.” These movements expressed their displeasure with the term “pagan,” considering it “fraught with centuries of prejudice and persecution.”) [9] The Uralic Communion, established in 2001, serves as an organization for cooperation among various institutions promoting indigenous religions in the Ural region. Within this context, a portion of the Erzya (2%) vehemently oppose Christianity, viewing it as a brainwashing doctrine designed to make people slavishly and blindly obedient. They regard their own religion as much more humane and natural. All these polytheistic neopagan religions or revivals of suppressed authentic religions provide space for various spirit beings, nature spirits, spirits of trees, special sacred places in nature, and ancient deities. This movement seems to be continuously growing.

Notes

[1] The term kern had a lot of overlapping meanings: corn; grain; kernel; the last handful or sheaf reaped at the harvest; a doll or figurine decorated with corn (or grain) flowers, etc., carried in harvest festivals, or harvest-home in celebration of a successful harvest as the kern baby, also called harvest queen. Kern comes from the Middle English curn, cooren, variant forms of English and Middle English corn, and also Dutch koren, kern, Old High German kerno, cherno, Middle High German kerne, kern, German Kern (core, kernel), the Old Norse kjarni, Icelandic kjarni, Danish kjerne, Swedish kärna (core, kernel); see also kernel. The Kern baby was the last English remnant of the ancient Ceres-festivals.

[2] The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 1983. ISBN 0-8018-4386-3. (First published in Italian as I benandanti, 1966)

Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath. New York. ISBN 0-226-29693-8. (First published in Italian as Storia notturna: Una decifrazione del Sabba, 1989)

[3] See literature list below.

[4] Bertrand Russell, engaging with the philosophical implications of quantum mechanics, shared his insights on the subject nearly a century ago. Yet, many enthralling quantum-theoretical ideas that should have changed our notions about ‘reality’ remain dormant, accumulating dust in a secluded ivory tower. The astronomer and paranormal researcher, Camille Flammarion, amassed a significant portion of his material on poltergeist outbreaks from reputable and factual police reports, underscoring the intersection of the mysterious and the tangible, and blurring the lines between perceived reality and the enigmatic. Even today, we observe an ongoing clash between commercially, politically, or by media-pressure influenced academic institutions and honest scientists, many of whom have faced cancellations lately. This underscores Martin Heidegger’s condemnation of modern science, when it erodes to nothing but a collection of administrative specialisms.

[5] Filatov, S., & Shchipkov, A. (1995). Religious Developments among the Volga Nations as a Model for the Russian Federation. Religion, State & Society, 23(3).

[6] (Conceptual and clinical implications of a “Haunted People Syndrome”. – Laythe, B., Houran, J., Dagnall, N., & Drinkwater, K. (2021). Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 8(3), 195–214.).

[7] When children try to scare each other, they often hide themselves, to appear quite suddenly and shout “Buh!” (“Boe!” in my country, the Netherlands – pronounced as Buh!). This “Buh” seems to be something Pan-European, as many cultures have Bogey’s with the root “pu”, “bu”, “bo”, “ba”, “pa” or a combination of these: bogeyman, puck (English), bogle (Scottish), bòcan, púca, pooka or pookha (Irish), pixie or piskie (Cornish), pwca, bwga or bwgan (Welsh), boeman (Dutch), butzemann, bögge, böggelmann (German), busemann (Norwegian), bøhmand / bussemand (Danish), puki ( Old Norse ), bubulis (Latvian), baubas (Lithuanian), mumus (Hungarian), bogu (Slavic), buka (Russian, бука), babau (Ukrainian, бабай ), bauk (Serbo-Croatian), bobo (Polish), abubakar (Czech and Slovak) torbalan (Bulgarian, торбалан) bebok (Silesian) pampoulas (Greek, Μπαμπούλας) bua (Georgian, ბუა) babau (Italian) baubau (Romanian), papão (Portuguese), babau (French). The bogey is a blanket-term for an imaginary folkloric creature that had the function of keeping children away from dangerous places; most often to prevent them from drowning, getting lost in a corn field etc. Sometimes the bogey is rooted in witch-like figures or some historical figure, who lived many centuries ago. Many bogeys are a hybrid product of some nature demon or field or water spirit, whose original role and being has been lost, or got eroded over time and became a “thought form” created by endlessly repeating certain stories and imaginings in the process. Many nature and field spirits who “remained intact” over the years have the bogeyman-phenomenon as a side effect.

[8] https://dil.ie/search?q=leprechaun; https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-49579940

[9] Svete, Aliide Naylor. (2022) The rituals of Paganism are making a comeback deep in the Baltic states

Literature:

Abercromby, J. (1898). The Pre- and Proto-historic Finns, both Eastern and Western with the Magic Songs of the West Finns (Vols. 1-2). David Nutt.

Adamah, B. (2022). Spirit Beings in European Folklore 1. VAMzzz Publishing, Amsterdam

Adamah, B. (2022). Spirit Beings in European Folklore 2. VAMzzz Publishing, Amsterdam

Adamah, B. (2022). Spirit Beings in European Folklore 3. VAMzzz Publishing, Amsterdam

Adamah, B. (2022). Spirit Beings in European Folklore 4. VAMzzz Publishing, Amsterdam

Árnason, J., Powell, G. E. J., & Magnússon, E. (1864). Icelandic Legends. Richard Bentley.

Arrowsmith, N. (1970/2009). Field Guide to the Little People: A Curious Journey Into the Hidden Realm of Elves, Faeries, Hobgoblins & Other Not-so-mythical Creatures. Llewellyn Worldwide.

Barb, A. A. (1966). Antaura. The Mermaid and the Devil’s Grandmother: A Lecture. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes.

Bardon, F. (2003). Die Praxis der Magische Evokation. Rüggeberg Verlag Wuppertal.

Bartsch, K. (1879). Sagen, Märchen und Gebräuche aus Meklenburg, vol. 1. Wilhelm Braumüller.

Benwell, G., & Waugh, A. (1961). Sea Enchantress: The Tale of the Mermaid and her Kin. Hutchinson.

Blau, L. (1974). Das Altjüdische Zauberwesen. Budapest/Graz.

Blécourt, W. de. (2007). “I Would Have Eaten You Too”: Werewolf Legends in the Flemish, Dutch, and German Area.

Bonnefoy, Y. (1993). Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press.

Bottiglioni, G. (1922). Leggende e tradizioni di Sardegna (testi dialettali in grafia fonetica).

Briggs, K. (1976). An Encyclopedia of Fairies: Hobgoblins, Brownies, Bogies and Other Supernatural Creatures. Pantheon Books.

Calmet, D. A. (1850). The Phantom World: The History and Philosophy of Spirits, Apparitions &c. &c. Two Volumes in One. A. Hart.

Campbell, J. G. (1900). Superstitions of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. James MacLehose and Sons.

Conway, M. D. (2015). Demonology and Devil-Lore (Vols. 1-2). VAMzzz Publishing, Amsterdam.

Conybeare, F. C. (2015). Testament of Solomon. Jewish Quaterly Review, October 1889. VAMzzz Publishing, Amsterdam.

Corstorphine, K., & Kremmel, L. R. (Eds.). (2018). Horror in the Medieval North: The Troll. In The Palgrave Handbook to Horror Literature. Palgrave

Courtney, M. A. (1890). Cornish Feasts and Folklore. Beare and Son.

Craigie, W. A. (1893). The Oldest Icelandic Folklore. Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

Davidsson, O. (1900). The Folk-lore of Icelandic Fishes. – published in The Scottish Review, October, pp. 312-332.

Dennison, W. T. (1891). Orkney Folklore, Sea Myths. Edinburgh University Press.

Dörler, A. F. (Ed.). (1895). Sagen aus Innsbruck’s Umgebung, mit besonderer Berücksichtigung des Zillerthales. Innsbruck.

Edmondston, T. (1866). An Etymological Glossary of the Shetland & Orkney Dialect. Adam and Charles Black.

Encyclopedia Brittanica online.

Folkard, R. (2021). Plant Lore Legends & Lyrics. (Original work published 1884). VAMzzz Publishing, Amsterdam.

Frazer, J. G. (1906-15). The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. The Macmillan Press Ltd

Genesin, M., & Rizzo, L. (Eds.). (2013). Magie, Tarantismus und Vampirismus; Eine interdisciplinäre Annäherung. Verlag Dr. Kovač, Hamburg.

Gibbings, W. W. (1892). Folk-lore and Legends – Germany.

Gieysztor, A. (2006). Mitologia Słowian. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

Gill, W. W. (1932). A Second Manx Scrapbook. Arrowsmith.

Grimm, J. (1835). Deutsche Mythologie. Dieterich.

Hageland, A. van. (1973). La Mer Magique. Marabout.

Hall, M. P. (1928). The Secret Teachings of All Ages: An Encyclopedic Outline of Masonic, Hermetic, Qabbalistic and Rosicrucian Symbolical Philosophy. reprint 2006, Tarcher

Hanaur, J. E. (1907). Folk-Lore of the Holy Land – Moslim, Christian and Jewish. Duckworth & Co.

Henderson, W. (1866). Notes on the folk-lore of the northern counties of England and the borders. Longmans, Green.

Hlidberg, J. B., Aegisson, S., McQueen, F. J. M., & Kjartansson, R. (2011). Meeting with Monsters. JPV utgafa.

Huizinga-Onnekes, E. J. (1930). Groninger Volksverhalen, bewerkt door K. ter Laan. J.B.Wolters’ Uitgevers Maatschappij N.V.

Johnston, S. I. (2013). Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece. University of California Press.

Karakurt, D. (2011). Türk Söylence Sözlüğü (Turkish Mythological Dictionary – online version).

Kivilson, V. A., & Worobec, C. D. (2020). Witchcraft in Russia and Ukraine, 1000–1900: A Sourcebook. Cornell University Press, Northern Illinois University Press.

Kreuter, P. M. (2001). Der Vampirglaube in Südosteuropa. Studien zur Genese, Bedeutung und Funktion. Rumänien und der Balkanraum. Weidler.

Lachower, F., Tishby, I., & Goldstein, D. (1994). Wisdom of the Zohar: An Anthology of Texts.

Lecouteux, C. (2003). Witches, Werewolves and Fairies: Shapeshifters and Astral Doubles in the Middle Ages. Inner Traditions.

Lecouteux, C. (2009). The Return of the Dead: Ghosts, Ancestors and the Transparent Veil of the Pagan Mind. Inner Traditions.

Lecouteux, C. (2010). The Secret History of Vampires: Their Multiple Forms and Hidden Purposes. Inner Traditions.

Lecouteux, C. (2011). Phantom Armies of the Night: The Wild Hunt and Ghostly Processions of the Undead. Inner Traditions.

Lecouteux, C. (2013). The Tradition of Household Spirits. Ancestral Lore and Practice. Inner Traditions.

Lecouteux, C. (2015). Demons and Spirits of the Land: Ancestral Lore and Practices. Inner Traditions.

Lecouteux, C. (2018). The Hidden Historie of Elves and Dwarfs – Avatars of Invisible Realms. Inner Traditions.

Libera, R. (2010). Storie di streghe, fantasmi e lupi mannari nei Castelli Romani. Consorzio SBCR editore.

Lindley, C., Viscount Halifax. (1936). Lord Halifax Ghost Book.

Lomas, A. G. (1964). Mitología y supersticiones de Cantabria.

Luzel, F. M. (1881). Contes populaires de Basse-Bretagne.

Mackenzie, D. A. (1917). Wonder Tales from Scottish Myth and Legend. Blackie and Son Limited, London, Glasgow, Bombay.

Mackenzie, D. A. (1935). Scottish Folk-Lore and Folk Life. Studies in Race, Culture and Tradition.

Mackenzie, D. A. (1909). Elves and Heroes.

Mackenzie, D. A. (1934). Teutonic Myth and Legend (2nd ed.).

Mannhardt, W. (1865). Roggenwolf und Roggenhund – Beitrag zur Germanischen Sittenkunde. Verlag von Constantin Ziemssen, Danzig.

Mannhardt, W. (1868). Die Korndämonen, – Beitrag zur Germanischen Sittenkunde. Harrwitz und Gossmann, Berlin.

Mannhardt, W. (1875). Wald- und Feldkulte. Band 1: Der Baumkultus der Germanen und ihrer Nachbarstämme: mythologische Untersuchungen. Gebrüder Borntraeger, Berlin.

Mannhardt, W. (1877). Wald- und Feldkulte. Band 2: Antike Wald- und Feldkulte aus nordeuropäischer Überlieferung erläutert. Gebrüder Borntraeger, Berlin.

Mannhardt, W. (1884). Mythologische Forschungen. Karl J. Trüber, Strassburg-London.

Marliave, O. de. (1987). Trésor de la mythologie pyrénéenne. Esper.

Masani, R. P. (1918). Folklore of Wells, being a study of Water Worship in East and West. D.B. Takapokevale Sons & Co.

Mathers, S. L. M. (1989). Kabbala Denudata / The Kabbalah Unveiled. Samuel Weiser Inc.

McAnally, D. R. (1888). Irish Wonders: The Ghosts, Giants, Pookas, Demons, Leprechawns, Banshees, Fairies, Witches, Widows, Old Maids, and other marvels of the Emerald Isle. The Riverside Press Cambridge.

McIntosh, A. (2005). “Faerie Faith in Scotland” in The Encyclopaedia of Religion and Nature.

McPherson, R. J. M. (1929). Primitive Beliefs in the North-East of Scotland. Longmans, Green and Co., Ltd.

Meyer, E. H. (1930). Mythologie der Germanen. Verlag von Karl J. Trübner.

Nadmorski, D. (1892). Kaszuby i Kociewie. Język, zwyczaje, przesądy, podania, zagadki i pieśni ludowe w północnej części Prus Zachodnich.

Petiteau, F.-E. (2007). Contes, légendes et récits de la vallée d’Aure. Alan Sutton.

Plancy, C. de. (1818). Dictionnaire Infernal.

Podgórscy, B., & Podgórscy, A. (2005). Wielka Księga Demonów Polskich. Leksykon i antologia demonologii ludowej. KOS.

Rajki, A. (2006-2009). Mongolian Ethymological Dictionary. Via academia.edu.

Ralston, W. R. S. (1872). Russian Fairy Tales – A choice collection of Muscovite folk-lore. Hurst & Co.

Ritter, J. N. von A. (1861). Deutsche Alpensagen.

Rose, C. (2000). Giants, Monsters, and Dragons. W. W. Norton and Co.

Rosenthal, B. G. (Ed.). (1997). The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture. Cornell University.

Rhys, J. (2020). Celtic Folklore Welsh and Manx. Library of Alexandria.

Ryan, W. F. (1999). The Bathhouse at Midnight – An Historical Survey of Magic and Divination in Russia. Pennsylvania State University Press.

Sacaze, J. (1887). Le dieu Tantugou, légende du pays de Luchon. (Revue de Comminges, Tome III, p. 116-118).

Saxby, J. M. E. (1932). Shetland Traditional Lore. Grant and Murray.

Sébillot, P. (1904). Le Folk-Lore de France, Tome Premier: Le Ciel et la Terre.

Sikes, W. (1880). British Goblins: Welsh Folk-Lore, Fairy Mythology, Legends and Traditions.

Simpson, J. (1972). Icelandic Folktales and Legends. University of California Press.

Sinastrari of Ameno. (2017). Incubi and Succubi or Demoniality – A Historical Study of Sexual contacts with Demons. VAMzzz Publishing, Amsterdam.

Sluijter, P. C. M. (1936). IJslands Volksgeloof. H. D. Tjeenk Willink & Zoon N.V.

Spada, D. (2007). Gnomi, Fate e Folletti e altri esseri fatati in Italia. SugarCo.

Spiesberger, K. (1978). Naturgeister wie Seher sie schauen – wie Magier sie rufen. Richard Schikowski Verlag.

Stefánsson, V. (1906). Icelandic Beast and Bird Lore.

Summers, M. (2001). The Vampire in Lore and Legend. (Previously published as: The Vampire in Europe, London, 1929).

Ter Laan, K. (1930). Groninger Overleveringen. Erven B. van der Kamp.

Thompson, F. (1976). The Supernatural Highland. Robert Hale.

Thorpe, B. (1852). Northern mythology: comprising the principal popular traditions and superstitions of Scandinavia, North Germany, and the Netherlands.

Veen, A. J. van der. (2017). Witte wieven, weerwolven en waternekkers – Een beschrijving van alle geesten, elfen en andere wondere wezens uit Nederland.

Vries, A. de. (2007). Flanders: a cultural history. Oxford University Press.

Wippel, I. (1986). Schabbock, Trud und Wilde Jagd. Verlag für Sammler.

Wlislocki, H. von. (1891). Volksglaube und religiöser Brauch der Zigeuner. Aschendorffsche Buchhandlung.