Abakua – the backgrounds of Cuba’s secret fraternity

Abakua (Abakuá) or Abakwa, sometimes called Ñáñigo, is an Afro-Cuban men’s initiatory fraternity or secret society, which originated from centuries old fraternal associations in the Cross River region of southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon, where the organization was known as the Leopard Society. (Not to be confused with the north eastern Congolese Leopard Men guerrilla groups who operated in the late 19th and early 20th century against the Belgium colonialists and natives who collaborated with them.)

Modern Abakua in Cuba

Ñáñigo is in fact a negative term, dating back to the 19th and early 20th century when there was an intense repression of the Abakua for their supposed associations with criminal gangs. Abakua operates in Cuba as a mutual-aid institution and has sometimes been described as an Afro-Cuban version of Freemasonry. The African Cross River Ékpè ‘leopard’ society was the primary model the society was build upon.

History

In Cuba the first societies were established as mutual-aid institutions in the town of Regla, Havana, in 1836. This remains the main area of Abakua implantation, especially the district of Guanabacoa in eastern Havana, and in Matanzas. In urban centers throughout the Portuguese and Spanish American colonies, African migrants organized cabildos — also called nation-groups — associations that included migrants of similar regions and language groups for purposes of mutual-aid. In the 1750s in Havana Cuba, five ‘Carabalí’ cabildos were documented, while others were created in the nearby port city of Matanzas. Carabalí’ leaders, born in Africa, eventually created Abakuá Cuban lodges for their children. The first Abakua lodges also functioned as part of an underground network of anti-colonial activity.

Abakua was therefore suppressed by the authorities, especially during crisis periods like in 1844, known as ‘the year of the lash’, when authorities tortured and killed many black Cubans suspected of participating in the anti-colonial movement. The persecution of Abakua was intended to lead to its extinction, but in 1863 one Abakuá leader and his supporters strategically created a lodge for white Cubans, who happened to be the sons of illustrious and powerful families in the colonial government. Andrés Petit (a.k.a. Andrés Valdés Petit Cristo de los Dolores), a title-holder of the lodge Bakokó Efó in Havana, founded the first lodge of white men. The whites wanted to belong because Abakuá was exciting, and it was also emerging as a symbol of Cuban identity. Petit envisioned that the whites would help defend the Abakuá society against persecution. This lodge, called Mukarará Efó (white men of Efó), created many others.

Abakua today

At present in Havana, Matanzas and Cárdenas, there exist over 150 lodges with more than 20,000 members. Abakuá ritual activities are exclusive to these three ports cities. Because of its African heritage, as well as its history of resistance to authorities, for many in Cuba’s dominant classes, Abakuá remains a symbol of ‘backwardsness’, of marginality and even criminality. Nevertheless for many Abakuá members and their communities, Abakuá is a symbol of the Cuban nation itself, being founded much earlier than the nation (1902), and being a deep psychological marker for Cuban resistance to enslavement and subjugation.

Although Abakuá is known as a ‘religion’ by its members, it is more accurately described as a prestige club for a privileged few who were selected for membership. Even amongst the overall membership, only a few lodge leaders have access to the inner mechanics of the institution. Abakua have historically investigated and screened potential members for moral qualities, interviewing their families (especially their mothers) and their larger communities about their conduct. Those with anti-social behavior were not allowed.

Calabar (Nigeria) and Ékpè, the spiritual root of Abakuá

Abakua Nigeria (Ekpe)

In the 21st century Cuban Abakua members have been able to communicate with their counterparts in Calabar, Nigeria, leading to an unprecedented reexamination of the African sources of Abakua history and practice, as well as the role of Ékpè and Abakua in the trans-Atlantic Cross River region diaspora. In 2007 in Calabar an association of Ékpè lodges from various tribes was created, Calabar Mgbè, as an expression of the shared practice of Ékpè historically in the region.

Abakua members derive their culture from the Efik and Efo of the Cross River region in Nigeria, which Cubans call Carabali. The people of Big Qua Town in Calabar, the capital of Cross River State, Nigeria, are known as the Abakpa, the likely source for the name Abakua . Big Qua Town is the home of the president of the Calabar Mgbe or Ékpè. The Cuban Abakuá societies have a male-only membership, their Ékpè equivalent in the Cross River State are called lodges. Both the Cuban and Nigerian lodges are Ékpè lodges and in Calabar, there are also women’s societies, which were not transferred across the Atlantic. Ékpè is also known as Egbo, Mgbe, Ngbe, or Ugbe among the multi-lingual groups in the region.

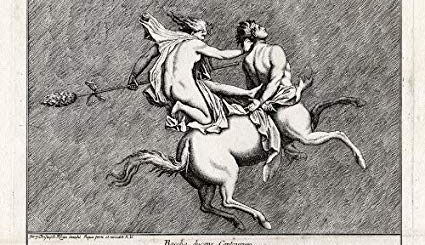

Apart from a term used for a fraternity organization, Ékpè has many meanings. Culturally Ékpè created rich entertainments comprising intricate dances, songs and body-mask performances by members. Spiritually members derive their belief systems and traditional practices from the Igbo, Efik, Efut, and Ibibio spirits that lived in the forest. Ékpè, according to lore, is a creature of untamed nature, a forest spirit that threatened humans and was therefore feared. But Ékpè also means “leopard,” which can be seen reflected in the block pattern in the costumes, in reference to leopard spots and the Leopard Men phenomena. Similar to the European werewolf tradition it was believed that some society members could transform themselves into leopards or project their astral body into a real leopard to stalk or kill their enemies. Finally, Ékpè was a school for esoteric teachings regarding human life as a cyclic process of regeneration including eventual reincarnation.

The Old Calabar slave trade

Víctor Patricio de Landaluze- El diablito (Little Devil)

The Ékpè Leopard Society was the oldest of cross river societies in West Africa. It was an all-male society most likely originating from a warrior society, but gaining importance during the slave trade which was centered in Calabar and dominated by the Efik people by the late 1700s. The trade brought wealth and a range of imported products into Calabar. The Efik, seeking to augment this wealth, also sold memberships in the society to other groups, enabling it to spread widely through the area. From the 1640s through the 1840s, Calabar, the main coastal port of the Cross River region, was an important embarking point for the Atlantic slave trade. People forcibly migrated from there to the Caribbean and Americas were known as ‘Carabalí’ (reversing the ‘l’ and the ‘r’) after this port, which was known as ‘Old Calabar’ from the 17th to the early 20th centuries.

Spread to Florida Cities with many Afro-Cuban immigrants in Florida such as Key West and Ybor City had a religion known by observers as “Nañigo” which was referred to as “Carabali Apapa Abacua” by practitioners. By the 1930s much of the religion seemed to have disappeared from visibility.

For Abakua lodges to be formed a structured initiation rite must be performed, something difficult to do for immigrant Abakuá members who are estranged from established lodges in Cuba. For this reason there is a debate as to whether the practices described as “Nañigo” were official Abakuá practices or simply imitations done by members estranged from official lodges. The term “Nañigo” itself was often used to describe any Afro-Cuban traditions practiced in Florida, and is thus not reliable to use to describe any set of traditions with accuracy.

No Abakuá lodges had been formed in Miami until 1998 an Abakuá group declared its existence in Miami only for Cuban Abakua members to denounce it since their lodge wasn’t officially consecrated with sacred materials only found in Cuba.

Membership and loyalty

Members of this society came to be known as Ñáñigos, a word now used to designate the street dancers of the society. The Ñáñigo, who were also called Diablitos, were well known by the general population in Cuba through their participation in the Carnival on the Day of the Three Kings, when they danced through the streets wearing their ceremonial outfit, a multicolored checkerboard dress with a conical headpiece topped with tassels.

The oaths of loyalty to the Abakua society’s sacred objects, members, and secret knowledge taken by initiates are a lifelong pact which creates a sacred kinship among the members. The duties of an Abakuá member to his ritual brothers at times surpass even the responsibilities of friendship, and the phrase “Friendship is one thing, and the Abakuá another” is often heard. One of the oaths made during initiation is that one will not reveal the secrets of the Abakua to non-members, which is why the Abakuá have remained hermetic for over 160 years.

Nigerian Folk Stories Collected From The Efik, Ibibio & People of Ikom

Ceremonies

Besides acting as a mutual aid society, the Abakua performs rituals and ceremonies, called plantes, full of theatricality and drama which consists of drumming, dancing, and chanting in the secret Abakua language. Knowledge of the chants is restricted to Abakua members, but Cuban scholars have long thought that the ceremonies express Abakuá cultural history. Other ceremonies such as initiations and funerals, are secret and occur in the sacred room of the Abakua temple, called the famba.

Music

Landaluze’s depiction of El Ñáñigo

The rhythmic dance music of the Abakua combined with Bantu traditions of the Congo contributed to the musical tradition of the rumba. Although hermetic and little known even within Cuba, an analysis of Cuban popular music recorded from the 1920s until the present reveals Abakua influence in nearly every genre of Cuban popular music. Cuban musicians who are members of the Abakuá have continually documented key aspects of their society’s history in commercial recordings, usually in their secret Abakua language. The Abakua have commercially recorded actual chants of the society, believing that outsiders cannot interpret them. Because Abakua represented a rebellious, even anti-colonial, aspect of Cuban culture, these secret recordings have been very popular.

Dance and broom

Ireme is the Cuban term for the masked Abakua dancer known as Idem or Ndem in the Cross River region. The masquerade dancer is carefully covered in a tight-fitting suit and hood, and dances with a broom and a staff. The broom serves to cleanse faithful members, while the staff chastises enemies and Abakuá traitors. During initiation ceremonies, the staff is called the Erí nBan nDó, while during mournings and wakes it is called Alan Manguín Besuá.

Language

Due to the secrecy of the society, little is known of the Abakua language. It is assumed to be a creolized version of Efik or Ibibio, both closely related languages or dialects from the Cross River region of Nigeria, because this is the cultural region and ethnic groups where the society originated.

You may also like to read:

doctor-john-or-jean-montenee-new-orleans-voodoo-king

the-seven-nanchons-or-loa-families-in-vodou

new-orleans-superstitions