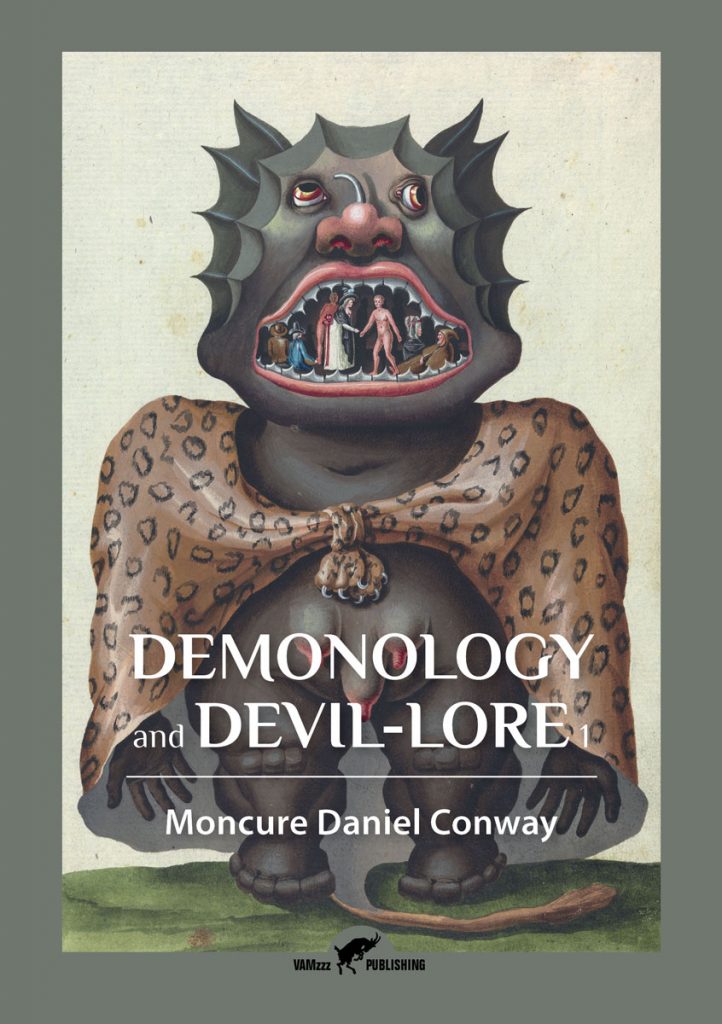

Demonology and Devil-Lore

Demonology and Devil-Lore 1 & 2 were both published in 1897. Within the demonology scope, this rare and mostly forgotten, almost 1000 pages thick masterpiece, remains unsurpassed in quality and completeness. Even in the 21st century the works offer fascinating missing links for both the academic and student of occult traditions. Author Moncure Daniel Conway’s bio is as revolutionary as his writings…

Moncure Daniel Conway (Stafford County, March 17, 1832 – Paris, November 15, 1907) was an American writer, abolitionist, Methodist, Unitarian and Freethought minister. The historian John d’Entremont described him as “the most thoroughgoing white male radical produced by the antebellum South.”

Conway descended from patriotic and patrician families of Virginia and Maryland. He spent most of the second half of his life abroad in England and France, and led freethinkers in London’s South Place Chapel. He was a prolific author who published over 70 volumes. Many of his works concern social issues, and several focus on abolitionism, the availability of education for everyone, biographies and religious topics. Solomon and Solomonic Literature (1899), Demonology and Devil Lore part 1 and 2 (1879) and The Natural History of the Devil (1859) deal with occult subjects, be it in a historical, analytical and philosophical direction.

Freeing the slaves of his father

Conway was born in Falmouth, Stafford County, Virginia, to parents descended from the First Families of Virginia. His father, Walter Peyton Conway was a wealthy slave-holding gentleman farmer, county judge and state representative. Conway’s mother, Margaret Stone, was the granddaughter of Thomas Stone of Maryland (a signer of the Declaration of Independence). In addition to running the household, she also practiced homoeopathy, she had learned from her father. After attending the Fredericksburg Classical and Mathematical Academy, Conway followed his older brother to Methodist-affiliated Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, graduating in 1849. During his time at Dickinson, Conway helped to found the college’s first student publication and came under the influence of Professor John McClintock, which caused him to embrace Methodism as well as an anti-slavery position. He first openly allied himself with abolitionists in July 1854 in the aftermath of the capture in Boston, of fugitive slave Anthony Burns. During the American Civil War (1861–1865), Conway accompanied thirty-one of his father’s slaves, all of whom had escaped to Washington, D.C., on a harrowing train ride to freedom in southwestern Ohio. There he established what came to be known as the Conway Colony.

In June 1858, he married a feminist, Ellen Davis Dana, a well-schooled daughter of a prominent businessman, at the First Unitarian Church of Cincinnati, where he became minister in 1856. Ellen was also a fellow Unitarian and abolitionist. The couple had three sons (two of whom survived childhood) and a daughter during their long marriage, which ended with her death from cancer in 1898. In 1859 Conway abandoned Unitarianism for free thought, telling his congregation of the First Unitarian Church of Cincinnati, Ohio, that he no longer believed in miracles or Christ’s divinity. A third of its members promptly left the church, but Conway’s new “Free Church” survived. His liberal views were published in Dial, a short-lived literary and journalistic monthly (1860).

Conway moved to Cincinnati in 1862. There he was particularly impressed with several German intellectuals in the city, especially John B. Stallo and August Willich, the latter of whom sharpened Conway’s perception of the problems faced by labour in the industrializing city. Under the influence of German free thinkers, Conway’s theology moved further to the left as he studied David Frederich Strauss’s Das Leben Jesus and began to question the veracity of Biblical accounts of miracles, the divinity of Jesus, and the authority of the Bible.

During the occupation before the devastating Battle of Fredericksburg, Conway also returned home to Falmouth in 1862, and learned that his family’s house had been saved from demolition because of its connection with him, although it was commandeered for use as a hospital for injured soldiers. That year, Conway published another powerful plea for emancipation, The Golden Hour. After spending more and more time away from his church advancing the abolitionist cause, and growing dissatisfied with the theological, liturgical, and social conservatism of mainstream Unitarianism, Conway left that denomination’s ministry, after which he maintained an uneasy and uncertain relationship with Unitarianism in America and subsequently in England until he and Ellen made a clean break.

Leaving America

In 1863, while on a speaking tour in England, Conway’s antislavery passion—not to mention his frustration with Lincoln’s sometimes overly cautious approach to emancipation—brought him into trouble with his own government, when he attempted to bargain with the Confederate envoy to Britain, James Murray Mason. Conway, who claimed falsely to speak for the abolition movement, offered to support disunion if the Confederates agreed to release their slaves. It was a proposal that did not come with the approval of the Lincoln administration, or anyone else for that matter. Confederates took pleasure in Conway’s misstep, while abolitionists back home, most of whom had become thoroughgoing wartime nationalists, howled in protest. Conway, fearful of having his passport revoked, meekly apologized to U.S. secretary of state William H. Seward. In the meantime, Conway was being drafted to serve in the army of the Union (likely the work of a political foe) but paid someone to take his place.

‘His many literary and intellectual friends included Charles Dickens, Robert Browning, Thomas Carlyle, Charles Lyell, and Charles Darwin.’

Rather than go back to America, where Conway no longer felt welcome as a suspected traitor to his childhood Virginia friends and neighbours, Conway travelled to Italy. There he reunited with his wife and children in Venice before moving back to London. There in 1864 he became minister of the South Place Chapel (serving in 1864–65 and 1893–97) as well as leader of the then named South Place Religious Society in Finsbury, London. Women were allowed to preach at South Place Chapel; among them the famous theosophist Annie Besant, whom Mrs. Conway had befriended. After his son Emerson died in 1864, Conway abandoned theism. His thinking continued to move from Emersonian transcendentalism toward a more humanistic Freethought.

Conway continued writing and publishing, including articles in both British and American magazines. In 1868 he was one of four speakers at the first open public meeting in support of women’s suffrage in Great Britain. His many literary and intellectual friends included Charles Dickens, Robert Browning, Thomas Carlyle, Charles Lyell, and Charles Darwin. He also served as a war correspondent during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. Conway published biographies of Edmund Randolph, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Thomas Paine, as well as acted as the American agent for Robert Browning and the London literary agent for Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, Louisa May Alcott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Conway attended the salon of radicals Peter and Clementia Taylor at Aubrey House in Campden Hill, West London. He also was a member of Clementia’s “Pen and Pencil Club”, at which young writers and artists read and exhibited their works. Conway even moved to Notting Hill to be near the Taylors at Aubrey House.

In the 1870s and 1880s Conway occasionally returned to the United States, where he reconciled with his Virginia family in 1875. In 1897 he and his now terminally-ill wife Ellen returned from London to New York City to fulfil Ellen’s wish of dying on American soil; she passed away on Christmas Day. Their son Dana also died that year. As the Spanish–American War approached, Conway turned toward pacifism and became estranged with his countrymen, moving to France to devote much of the remainder of his life to the peace movement and composition. However, he occasionally returned to Fredericksburg, which had come to admire his cultural accomplishments.

Conway also travelled to India, about which he wrote shortly before his death in his Parisian apartment on November 15, 1907. His body was ultimately returned to Westchester County, New York, for burial in the Kensico cemetery beside his wife Ellen, and their children (only his son Eustace survived both parents, dying in 1937). Conway Hall in Holborn, London is named in his honour. In 2004, Virginia Governor Mark R. Warner proclaimed Conway the only descendant of a Founding Father of the nation to physically lead slaves to freedom. Both Ohio and Virginia have erected historical markers in his honour, and Conway’s childhood home was designated a U.S. and Virginia landmark. ♦

VAMzzz Publishing book:

Conway divides Volume 1 of Demonology and Devil Lore in three parts and deals mainly with the evolution and thematic classification of ex-gods, demons and nature creatures. Part 1 offers information about the dawn of dualism, the political degradation of gods into demons due to theological animosity, and the difference between demon and devil.

Part 2 of Demonology and Devil Lore examines the demonic realm, according to themes like hunger, heat, cold, the Elements, animals, darkness, dogs, storm, Walpurgis night, cats etc.. Part 3 is focussed extensively on the serpent, dragon, worm, the decline and generalization of demons, and we also encounter the werewolf and basilisk, among much more.

Volume 2 deals primarily with the diabolic and with the Devil himself, his ethnic history and connected topics; themes like Ahriman and Ormuzd, women and the Star-Serpent in Persia, Lilith, Samael, Kali, Satan, Tiamat, Bohu, Ra and Apophis, Typhon, Gnostic theories, exorcism, Black Art Schools, the blood covenant, the witches Sabbath, the goat and cat, the Wild Hunt, Faust and Mephistopheles, magic seals, The Raven Book, Papal sorcery and a lot more.

Demonology and Devil-Lore 1 and 2

by Moncure Daniel Conway

English

Paperback, book sizes 148 x 210 mmVolume 1: 490 pages, ISBN 9789492355157

Volume 2: 518 pages, ISBN 9789492355164